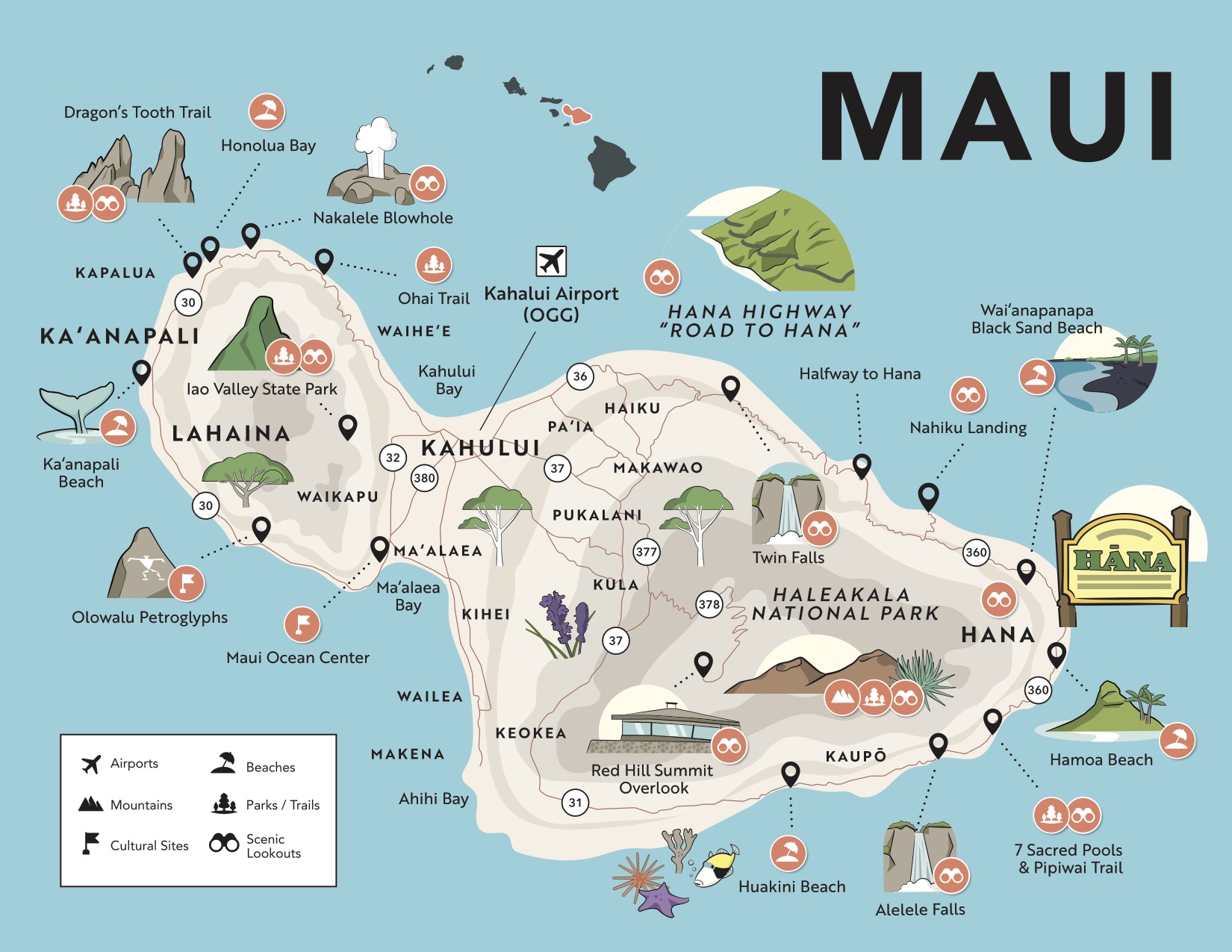

On the western shores of Maui, nestled against the world-famous Kaʻanapali Beach, lies Black Rock Beach, one of the island’s most unique coastal gems. Known locally as Puʻu Kekaʻa, this dramatic lava point is more than just a picturesque spot—it’s a place where Hawaiian culture, natural beauty, and outdoor adventure come together. For travelers seeking both relaxation and excitement, Black Rock Beach offers an unforgettable experience that combines history, snorkeling, cliff diving, and breathtaking sunsets.

Black Rock Beach is located at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach, one of Maui’s most visited and celebrated shorelines. Stretching for about three miles, Kaʻanapali Beach is known for its soft golden sand, turquoise waters, and views that sweep across the Pailolo Channel toward Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi. At its northernmost point, the volcanic lava formation known as Black Rock juts dramatically into the ocean, creating a striking contrast against the sandy expanse of the beach.

This natural barrier not only adds beauty to the landscape but also shapes the underwater environment. The lava rock formation provides shelter for an abundance of marine life, making the area around Black Rock one of the best snorkeling destinations on Maui.

Beyond its scenic appeal, Black Rock holds deep cultural importance in Hawaiian tradition. According to Hawaiian legends, Puʻu Kekaʻa is believed to be a leina, or a jumping-off point, where spirits would leap into the afterlife to join their ancestors. Because of this sacred history, the site remains a revered place that blends spirituality with natural wonder.

To honor this heritage, the Sheraton Maui Resort, located adjacent to Black Rock, continues a long-standing tradition of a nightly cliff diving ceremony. At sunset, a torchbearer lights the tiki torches along the cliff, climbs to the top, and dives gracefully into the ocean—symbolizing the legendary feats of Maui’s ancient chiefs. This ceremony connects visitors to the island’s rich cultural past while offering a breathtaking spectacle.

One of the biggest draws of Black Rock Beach is snorkeling. The waters around the lava point are teeming with tropical fish, sea turtles (honu), and vibrant coral. Beginners and experienced snorkelers alike will find plenty to enjoy, as the area is accessible directly from the shore and offers relatively calm conditions, especially in the mornings.

Some of the marine life commonly spotted here includes:

Because Black Rock provides a natural barrier, visibility is often excellent, making it ideal for underwater photography and close encounters with Maui’s marine biodiversity.

For those seeking adrenaline, cliff diving off Black Rock has become one of the most iconic activities in Kaʻanapali. While the jump itself is about 20 to 30 feet, the thrill of leaping into the clear waters below against the backdrop of a Hawaiian sunset is unforgettable. Many visitors gather in the evening to watch brave locals and visitors alike take the plunge.

It’s worth noting that safety should always come first—conditions can change quickly, and the ocean demands respect. Anyone considering a dive should ensure calm waters and proper physical ability before attempting it.

Black Rock Beach is also one of the best spots on Maui to watch the sunset. As the sun sinks into the Pacific, the cliffs and ocean reflect brilliant shades of orange, pink, and purple. From the vantage point of Black Rock, you may also catch a glimpse of the neighboring islands silhouetted against the evening sky. During the winter months, it’s not uncommon to see humpback whales breaching offshore, adding even more magic to the scene.

Black Rock Beach is easily accessible, located at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach and near many resorts, shops, and restaurants. Public beach access and parking are available, though spots can fill quickly during peak times. Visitors should plan ahead and consider arriving early to secure parking and enjoy the calmer morning waters for snorkeling.

Because Black Rock Beach is connected to the resort area, amenities such as restrooms, dining options, and rentals for snorkeling gear are nearby. This makes it a convenient destination for families, couples, and solo travelers alike.

Black Rock Beach in Kaʻanapali, Maui, offers much more than a stunning shoreline. It’s a place where Hawaiian culture is alive, where adventure meets tranquility, and where visitors can experience the best of Maui’s natural beauty. Whether you come for snorkeling, cliff diving, or simply to soak in a legendary sunset, Black Rock Beach promises an experience you’ll never forget.

1. What makes Black Rock Beach in Maui so special?

Black Rock Beach—also known as Puʻu Kekaʻa—is unique because it blends stunning natural beauty, rich Hawaiian cultural history, incredible snorkeling, and cliff diving into one unforgettable experience. Located on the northern end of famed Kaʻanapali Beach, it’s a place where adventure, relaxation, and tradition meet. Visitors can explore marine life, enjoy sunsets, and take in one of Maui’s most iconic oceanfront ceremonies.

2. Where exactly is Black Rock Beach located?

Black Rock Beach sits at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach, one of Maui’s best-known shorelines. The dramatic lava formation juts into the Pacific Ocean, creating a natural point that divides the beach and also protects the reef below. It’s easily accessible from Kaʻanapali’s resorts, boardwalk, and public beach access areas.

3. What is the natural setting like at Black Rock Beach?

Black Rock Beach is famous for its golden sand, turquoise waters, and striking black lava point. The views extend across the Pailolo Channel toward the islands of Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi. The lava rock formation not only creates a beautiful backdrop but also helps shelter marine life, making the waters especially clear and rich with sea creatures.

4. What is the cultural significance of Black Rock (Puʻu Kekaʻa)?

In Hawaiian tradition, Puʻu Kekaʻa is believed to be a leina, or spiritual “jumping-off point,” where souls would leap into the afterlife. This makes it a sacred and deeply respected place. To honor this heritage, the Sheraton Maui continues the historic nightly cliff diving ceremony, featuring torches, storytelling, and a symbolic dive at sunset. This ceremony reflects the feats of ancient Hawaiian chiefs and connects visitors to the island’s cultural past.

5. Is Black Rock Beach a good place for snorkeling?

Yes—Black Rock is one of Maui’s top snorkeling spots. The lava formation provides shelter for many species of marine life, and visibility is often excellent, especially in the mornings. Snorkelers commonly see tropical fish like butterflyfish, parrotfish, and Moorish idols, as well as Hawaiian green sea turtles (honu). The area is easy to access directly from the shore, making it great for both beginners and experienced snorkelers.

6. Can you go cliff diving at Black Rock?

Cliff diving is one of the most iconic activities at Black Rock. The jump is usually 20–30 feet depending on tide levels. Many visitors try it, especially during calm ocean conditions. However, safety should always come first—check the water conditions, avoid rough surf, and only jump if you’re confident and capable. Many people prefer to watch the brave divers rather than jump themselves.

7. What is the sunset like at Black Rock Beach?

Black Rock is one of Maui’s best sunset spots. As the sun dips into the ocean, the sky glows with shades of pink, orange, and purple. The silhouette of Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi adds to the beauty, and during winter months, you may even see humpback whales breaching offshore. The nightly cliff diving ceremony at sunset also makes the moment even more memorable.

8. Is Black Rock Beach easy to access, and are there facilities nearby?

Yes. Black Rock Beach is located right next to major Kaʻanapali resorts, so amenities like restrooms, dining options, and snorkel rentals are close by. Public beach access and limited parking are available, but parking fills up quickly—arriving early is recommended. The boardwalk makes it easy to walk from nearby hotels and shops.

9. When is the best time to visit Black Rock Beach for snorkeling or swimming?

Morning is typically the safest and calmest time for ocean activities. Winds and surf conditions tend to increase later in the day. Arriving early also helps with parking and ensures clearer visibility underwater. Always check the current ocean conditions, as the waters around Black Rock can change quickly.

10. Are there safety tips I should know before snorkeling or cliff diving at Black Rock?

Yes—ocean safety is essential:

11. What else can you do near Black Rock Beach?

Visitors can enjoy walking the Kaʻanapali Beach boardwalk, book snorkeling or whale-watching tours, dine at nearby restaurants, or relax on the wide expanse of Kaʻanapali Beach. The area is lively, walkable, and full of both cultural and adventure opportunities, making it perfect for families, couples, and solo travelers.

12. Why is Black Rock Beach considered a must-visit spot on Maui?

Black Rock Beach stands out because it blends natural beauty, Hawaiian culture, ocean adventure, and iconic sunsets in one unforgettable location. Whether you're snorkeling with turtles, watching a traditional cliff diving ceremony, or simply soaking in the view, it offers an authentic Maui experience you won’t find anywhere else.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

For many adventure seekers, nothing quite compares to the rush of gliding high above treetops, rivers, and mountains on a zipline. The activity, once primarily used as a means of transport in remote regions, has now become a worldwide attraction for those craving adrenaline, scenic beauty, and unique outdoor experiences. Today, ziplines are no longer just about speed and height—they’re about immersing yourself in nature, conquering fears, and creating lasting memories.

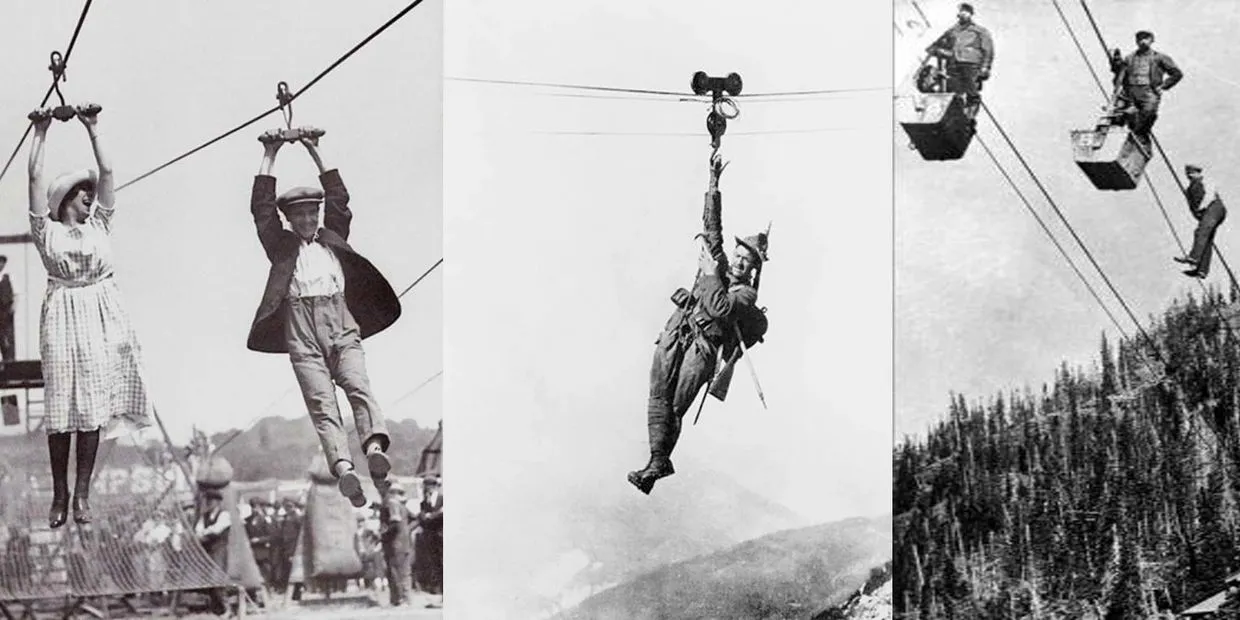

Though ziplining may seem like a modern adventure activity, its origins go back centuries. Villagers in remote areas of the Himalayas, China, and South America used early versions of ziplines as a practical way to transport goods, supplies, and even people across rivers and valleys where bridges were unavailable.

In Costa Rica during the 1970s, biologists popularized the concept of ziplines as a way to study rainforests without disturbing the fragile ecosystem. It wasn’t long before tourism companies recognized the thrill and beauty of this experience, transforming ziplining into the recreational activity we know today.

The core attraction of a zipline is simple: the exhilarating sensation of soaring through the air. Riders are strapped into a secure harness, clipped to a sturdy cable, and propelled by gravity as they glide from one platform to another. The speed, height, and exposure to open air create an adrenaline rush unlike any other.

Ziplines are often located in some of the most beautiful natural landscapes around the world. From tropical rainforests and mountain ridges to coastal cliffs and canyons, zipline tours allow riders to experience scenery from a bird’s-eye perspective. What might take hours to hike can be appreciated in moments while flying through the sky.

Unlike many extreme sports, a zipline does not require years of training or advanced fitness levels. Most tours are accessible to beginners, and professional guides provide safety briefings to ensure comfort and confidence. This makes ziplines a family-friendly adventure that appeals to kids, adults, and even seniors looking to step outside their comfort zones.

Corporate groups and schools often book zipline excursions as team-building activities. Facing a challenge together encourages trust, cooperation, and bonding. On a personal level, completing a ride helps individuals build confidence and overcome fears, particularly if they are afraid of heights.

One of the most common questions people ask before riding a zipline is whether it’s safe. The good news is that modern ziplines are built with strict safety standards and equipment designed to handle high tension and weight loads. Harnesses, helmets, and dual-line systems are common features. Operators are trained to inspect cables and platforms regularly, ensuring every ride meets professional safety requirements.

Before each ride, participants typically receive a briefing on proper techniques—how to hold the straps, where to keep their hands, and how to brake if necessary. Safety is always the top priority, allowing riders to focus on enjoying the adventure.

Not all ziplines are the same, and the variations add to the excitement:

If you’re planning your first zipline adventure, here are a few tips to make the most of it:

At its heart, ziplining is about more than the thrill of speed. It’s a way to connect with nature, to conquer personal challenges, and to share a unique experience with friends and family. The blend of excitement, safety, and accessibility has made ziplines one of the fastest-growing outdoor adventure activities worldwide.

Whether you’re gliding over a rainforest in Costa Rica, soaring above valleys in Hawaii, or trying an urban zipline in the city, the experience will leave you with a new perspective—both literally and figuratively.

1. What exactly is ziplining, and why do people love it so much?

Ziplining is an adventure activity where you glide through the air on a secure cable, usually while harnessed in. People love it because it combines adrenaline, incredible scenery, and the thrill of flying. It’s one of the few outdoor adventures that allows beginners to instantly experience the sensation of soaring over treetops, valleys, rivers, and mountains.

2. Where did ziplining come from originally?

Ziplining actually has ancient roots. Early versions were used in places like the Himalayas, China, and South America as a practical way to transport goods or people across rivers and deep valleys. In the 1970s, biologists in Costa Rica began using ziplines to study rainforests from above. That idea evolved into the recreational zipline tours we know today.

3. Why is ziplining such a popular adventure activity now?

People are drawn to ziplining because it offers:

4. Do I need to be super fit or experienced to ride a zipline?

No! Most ziplines are designed for beginners and families, and guides provide all safety instructions you need. As long as you meet the weight requirements and can climb a few stairs or platforms, you can enjoy the experience. Kids, adults, and even seniors can participate safely.

5. Is ziplining safe? How do operators ensure rider safety?

Ziplining is very safe when operated correctly. Modern ziplines follow strict engineering and safety standards. Safety measures typically include:

6. What types of ziplines are there around the world?

There are several kinds of zipline experiences, each offering its own thrill:

7. What are some of the most famous zipline destinations in the world?

Top zipline hotspots include:

8. What should I wear when ziplining for the first time?

Wear clothes you can move in—activewear is best. Avoid skirts, dresses, or loose accessories that can get tangled. Closed-toe shoes (like sneakers or hiking shoes) are essential for safe takeoffs and landings. Tie back long hair and leave dangling jewelry at home.

9. What should I expect during the safety briefing before a zipline tour?

Guides will walk you through:

10. Is ziplining a good activity for families or group outings?

Definitely. Ziplining is one of the best family-friendly adventures because it blends teamwork, encouragement, and shared excitement. Many corporate groups and school programs use ziplining as a team-building activity because it promotes trust and confidence.

11. How scary is ziplining if I’m afraid of heights?

It’s normal to feel nervous at first, but most people find that once they take off, the fear fades into excitement. Ziplining can actually help people overcome height-related fears because you're securely harnessed and supported the entire time. Guides are trained to help you feel safe and comfortable.

12. Why do people say ziplining is more than just a ride?

Ziplining offers a deeper experience beyond the thrill:

13. What tips should first-time zipliners know before going?

Here’s what helps most beginners:

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Snuggled along the northwestern coast of Maui, Kapalua is a breathtaking resort area that seamlessly blends natural beauty, cultural heritage, and modern luxury. Known for its pristine beaches, world-class golf courses, and lush landscapes, Kapalua offers visitors a chance to experience the very best of the Valley Isle in one stunning location. Whether you’re looking for relaxation, adventure, or a taste of Hawaiian history, Kapalua stands out as one of the most treasured destinations in Hawai‘i.

The word Kapalua translates to "two borders" or “arms embracing the sea,” a fitting name for this region where bays, lava rock peninsulas, and turquoise waters meet in harmony. Historically, the land was used for agriculture, particularly for growing pineapples, as part of the legacy of the Baldwin family and the Maui Land & Pineapple Company. Today, Kapalua maintains its ties to the past while embracing a new role as one of Maui’s premier resort areas.

Despite the development of luxury accommodations and championship golf courses, Kapalua’s commitment to environmental stewardship has helped preserve much of its natural beauty. Walking through the area, visitors can still feel the sense of connection between land and sea that has defined Maui for centuries.

Kapalua is home to some of Maui’s most famous beaches, each offering its own unique charm.

These beaches showcase Kapalua’s balance between adventure and relaxation, offering something for every type of traveler.

For golf enthusiasts, Kapalua is nothing short of legendary. The Plantation Course at Kapalua is home to the PGA TOUR’s Sentry Tournament of Champions, held each January. This event draws the world’s best golfers to compete against the backdrop of sweeping ocean views and the West Maui Mountains.

Designed by renowned architects Ben Crenshaw and Bill Coore, the Plantation Course is celebrated for its challenging design, rolling terrain, and panoramic vistas. Meanwhile, the Bay Course provides a slightly more forgiving but equally scenic experience, winding along the coastline with holes that hug the cliffs above the Pacific.

Even non-golfers can appreciate the beauty of these courses, which are integrated into the landscape in a way that enhances the natural surroundings.

Kapalua is not only a destination for beaches and golf but also a paradise for nature lovers. The Kapalua Coastal Trail stretches along the shoreline, offering a scenic walk through lava fields, beaches, and oceanfront cliffs. This easy-to-moderate trail is perfect for spotting whales during winter months or simply enjoying the changing landscapes of Maui’s coastline.

For those looking for a deeper immersion in nature, the Maunalei Arboretum Trail takes hikers into the upland forests above Kapalua. Once part of the pineapple plantation, this area has been restored with native Hawaiian plants, offering a glimpse of Maui’s ecological heritage.

Kapalua is synonymous with luxury. The Ritz-Carlton Maui, Kapalua and the Montage Kapalua Bay provide world-class accommodations that blend comfort with island-inspired elegance. These resorts feature spa experiences rooted in Hawaiian traditions, infinity pools overlooking the Pacific, and access to Kapalua’s finest amenities.

Dining in Kapalua is equally remarkable. Merriman’s Kapalua offers farm-to-table cuisine with an oceanfront setting that’s perfect for sunset dinners, while Sansei Seafood Restaurant & Sushi Bar is beloved for its creative Japanese-inspired dishes. Many of the restaurants in the area highlight locally sourced ingredients, ensuring that each meal reflects the flavors of Hawai‘i.

Beyond luxury and leisure, Kapalua is also a place that values cultural and environmental preservation. The annual Celebration of the Arts Festival, hosted at the Ritz-Carlton Maui, brings together Hawaiian artisans, musicians, and cultural practitioners to share their crafts and traditions. This event allows visitors to experience authentic Hawaiian culture in a meaningful way.

Additionally, conservation efforts such as the protection of marine life at Kapalua Bay and the preservation of native habitats along the trails reflect the community’s commitment to sustainability. These initiatives ensure that Kapalua remains not only a destination for today’s travelers but also for generations to come.

Whether you’re an adventurer, a golfer, a foodie, or someone simply looking to unwind in paradise, Kapalua offers a complete Hawaiian experience. Its combination of natural beauty, luxury amenities, cultural depth, and recreational opportunities make it one of the most remarkable places on Maui.

From sunrise strolls along the coastline to world-class golf in the afternoon and fine dining at sunset, Kapalua provides unforgettable moments at every turn. It’s more than just a destination—it’s an embrace of the sea, the land, and the spirit of aloha.

1. What makes Kapalua one of the best places to visit in Maui?

Kapalua is loved for its luxury resorts, world-class beaches, scenic trails, championship golf courses, and rich cultural history. Located on Maui’s northwestern coast, it blends natural beauty with modern comfort. Whether you’re looking for adventure, relaxation, or a sophisticated Hawaiian getaway, Kapalua offers a little bit of everything that makes Maui special.

2. What does the name “Kapalua” mean, and why is its history important?

“Kapalua” means “two borders” or “arms embracing the sea,” a fitting description for its stunning coastlines and sheltered bays. Historically, this region was part of the Baldwin family’s agricultural lands and was heavily tied to Maui’s pineapple plantation era. Today, Kapalua honors that past while evolving into one of Hawai‘i’s premier resort destinations—carefully balancing development with environmental stewardship.

3. Which beaches in Kapalua are the best for swimming and snorkeling?

Kapalua is home to some of Maui’s top beaches:

4. Is Kapalua Bay really one of the best beaches in the world?

Yes! Kapalua Bay has been ranked multiple times as one of the world’s best beaches, thanks to its crystal-clear water, crescent-shaped shoreline, and excellent snorkeling conditions. The protected bay creates a calm, tranquil setting that appeals to families, snorkelers, and anyone who wants a classic Hawaiian beach experience.

5. Why is Kapalua so famous for golf?

Kapalua is legendary in the golf world because it’s home to the Plantation Course, host of the PGA TOUR’s Sentry Tournament of Champions every January. Designed by Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, the course features incredible elevation changes and panoramic ocean views. The Bay Course offers a more forgiving but equally scenic golf experience, with holes that run right along the coastline. Even non-golfers love the views.

6. Are there good hiking or walking trails in Kapalua?

Absolutely. Kapalua is one of the most scenic areas on Maui for hiking. Popular trails include:

7. What luxury resorts can I stay at in Kapalua?

Kapalua is home to two of Maui’s top luxury resorts:

8. What are the best restaurants in Kapalua?

Kapalua has a great food scene, featuring farm-to-table dining and Pacific Rim cuisine. Favorites include:

9. Does Kapalua offer cultural experiences or events?

Yes. Kapalua honors Hawaiian culture through events like the Celebration of the Arts Festival, hosted at the Ritz-Carlton. Hawaiian artisans, musicians, and cultural practitioners share traditions through workshops, performances, and ceremonies. Conservation efforts, native habitat restoration, and marine protection at Kapalua Bay also reflect the area’s cultural and environmental responsibility.

10. What makes Kapalua different from other resort areas on Maui like Wailea or Kaʻanapali?

Kapalua stands out because it offers a quieter, more refined, and nature-focused experience. While Wailea is known for luxury and Kaʻanapali for its lively beach scene, Kapalua blends serenity with world-class amenities. Its protected bays, award-winning golf courses, dramatic scenery, and cultural depth make it ideal for travelers wanting a more laid-back yet upscale Maui vacation.

11. Is Kapalua a good place to see whales in the winter?

Absolutely. Kapalua offers fantastic whale-watching opportunities from December through April. Humpback whales migrate through the nearby channels, and it’s common to see them breaching from the beaches, coastal trails, and even the golf courses.

12. Why should I add Kapalua to my Maui itinerary?

Kapalua offers a complete Hawaiian experience:

Whether you want relaxation, adventure, luxury, or authentic cultural experiences, Kapalua delivers it all with an unmatched sense of aloha.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

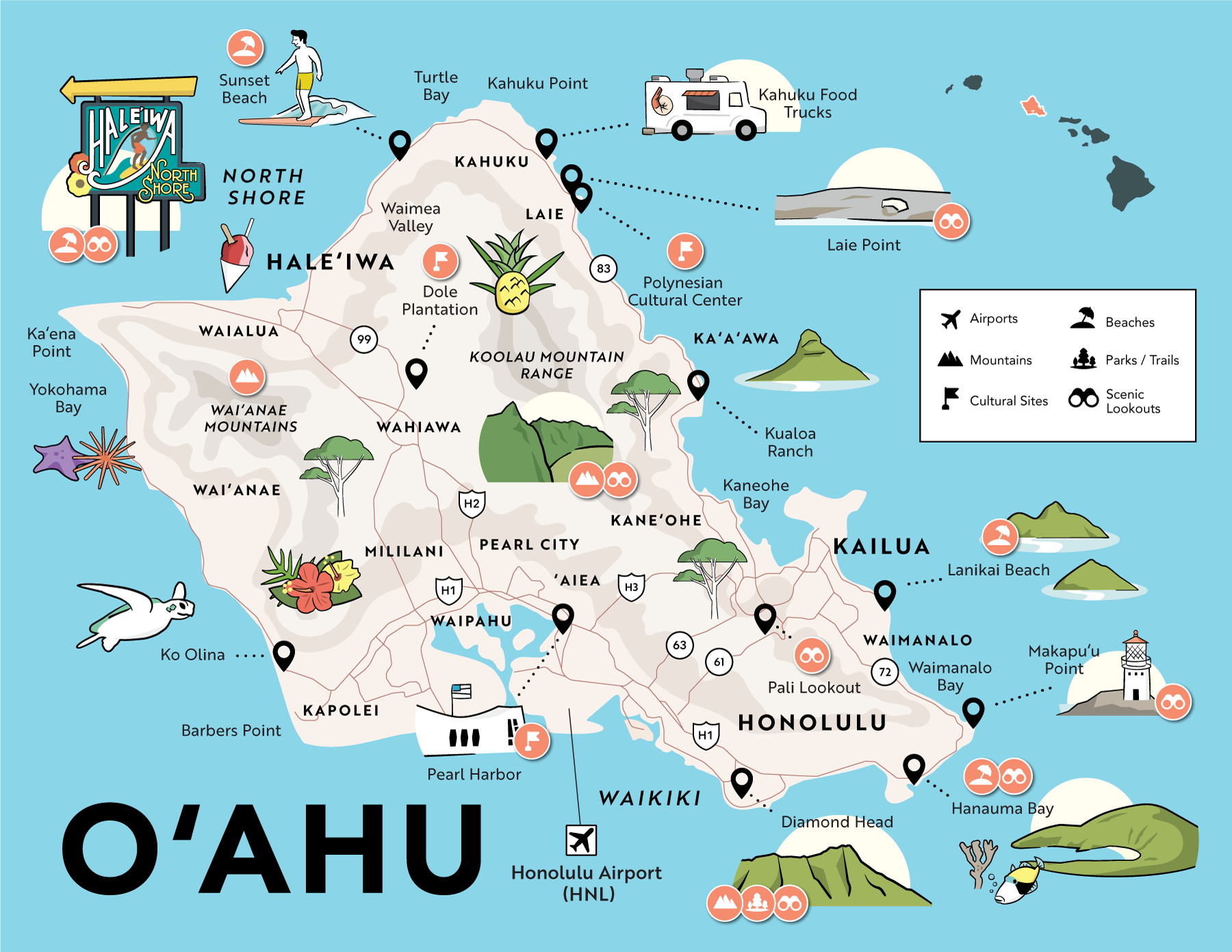

When people think of Hawaii, they often imagine swaying palms, white sand beaches, and volcanic landscapes. But another breathtaking sight that visitors and locals alike admire is the Hawaii skyline. Unlike the towering skyscraper silhouettes of New York or Los Angeles, Hawaii’s skyline tells a unique story—one where natural beauty, history, and urban development coexist in harmony. From the vibrant cityscape of Honolulu to the dramatic mountain ranges that serve as a backdrop, the skyline of Hawaii is one of the most distinctive in the world.

The most recognized skyline in the Hawaiian Islands belongs to Honolulu, the capital city located on Oʻahu. Honolulu is the economic and cultural hub of Hawaii, home to high-rise hotels, luxury condominiums, and office buildings that stretch skyward against a turquoise ocean backdrop.

Waikīkī, perhaps the most famous neighborhood of Honolulu, features a dense cluster of hotels and resorts. From the beach, the skyline looks like a vertical cityscape perched right on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. At sunset, the sight is particularly enchanting as golden light reflects off the glass windows of tall buildings, creating a warm glow.

What makes Honolulu’s skyline unique is its harmony with the surrounding natural features. The looming presence of Diamond Head Crater to the east provides a natural frame that contrasts with the manmade structures. Few cities in the world boast such a dramatic juxtaposition of volcanic landscapes with urban design.

Unlike other metropolitan skylines, Hawaii’s city silhouettes are rarely uninterrupted lines of steel and glass. Instead, they are deeply influenced by the islands’ volcanic origins. The Koʻolau Mountain Range rises sharply behind Honolulu, creating a dramatic green wall that defines the horizon. On Maui, the slopes of Haleakalā tower above towns and resorts, reminding viewers that nature remains the dominant force shaping the skyline.

This connection to the natural environment ensures that Hawaii’s skylines always maintain a sense of balance. Development is visible, but it never overshadows the mountains, cliffs, and craters that define the islands. Even when high-rises are built, strict zoning laws help prevent overdevelopment in certain areas, allowing the natural skyline to remain a focal point.

While Honolulu stands out as the most urbanized skyline in Hawaii, each island offers its own unique horizon worth admiring:

Hawaii’s skyline changes dramatically with the light.

Hawaii’s skyline is more than just a visual landmark—it’s also a reflection of the islands’ values. Hawaiian culture emphasizes respect for the land, known as mālama ʻāina, which influences how cities are designed and built. For example, many high-rises incorporate open-air designs and green spaces to connect urban living with the natural world.

In recent years, sustainable architecture has become a growing focus. New developments in Honolulu and other areas are prioritizing energy efficiency, solar integration, and eco-friendly materials. This approach ensures that while the skyline grows, it does so in a way that aligns with Hawaii’s commitment to protecting its environment.

The Hawaii skyline is a unique blend of manmade structures and natural wonders. While Honolulu offers the most recognizable cityscape, the skylines across the islands highlight volcanic peaks, lush mountain ranges, and dramatic coastlines that make Hawaii unlike anywhere else. Whether admired at dawn, dusk, or under a canopy of stars, the skyline here tells the story of a place where urban life and natural beauty coexist in harmony.

For visitors, the Hawaii skyline is more than just a backdrop—it’s a reminder of the islands’ delicate balance between progress and preservation, culture and modernity, earth and sky.

1. What makes the Hawaii skyline different from other city skylines in the world?

The Hawaii skyline is unique because it blends modern high-rises with dramatic natural landmarks like volcanic craters, lush mountains, and ocean views. Unlike cities dominated by steel and glass, Hawaii’s skyline showcases harmony between urban development and the islands’ incredible natural scenery. It’s a place where skyscrapers sit next to coral-blue waters and are framed by towering mountains.

2. Which island has the most famous and recognizable skyline in Hawaii?

The most iconic skyline belongs to Honolulu on Oʻahu. Known for its high-rise hotels, luxury condos, and the bustling Waikīkī district, Honolulu features the most urban skyline in the islands. What makes it stand out is its backdrop: Diamond Head Crater and the towering Koʻolau Mountains, creating one of the most scenic city-meets-nature skylines on Earth.

3. What does the skyline of Waikīkī look like?

The Waikīkī skyline is a dense cluster of beachfront hotels and resorts rising above the Pacific Ocean. Seen from the sand, it looks like a vertical city perched on the shoreline. At sunset, the buildings glow gold as the light reflects off the windows, creating one of the most photographed views in Hawaii.

4. How do Hawaii’s mountains influence the skyline?

Hawaii’s skyline is shaped heavily by its volcanic mountain ranges, which act as a dramatic natural backdrop.

5. What do the skylines on the different Hawaiian Islands look like?

Each island has its own distinct skyline:

6. When is the best time of day to admire the Hawaii skyline?

The Hawaii skyline changes beautifully throughout the day:

7. Why does Honolulu have more skyscrapers than the other Hawaiian islands?

Honolulu is the economic, cultural, and residential hub of Hawaii, making it the only island with a major urban center. Zoning laws and sustainability efforts keep development concentrated to preserve natural landscapes. Other islands limit building heights to ensure mountain views and protect the natural skyline.

8. How do volcanic landscapes contribute to the Hawaii skyline?

Volcanic formations like Diamond Head, Haleakalā, Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and the Koʻolau Range create iconic silhouettes that make Hawaii instantly recognizable. These natural structures are millions of years old and provide dramatic contrast to the modern architecture below, giving Hawaii’s skylines a sense of timeless beauty.

9. Are there sustainable or eco-friendly features in Hawaii’s skyline?

Yes. Hawaii is committed to mālama ʻāina—caring for the land. Many new buildings incorporate sustainable design, including solar power, open-air layouts, green spaces, and energy-efficient materials. This approach allows Hawaii to modernize without compromising environmental values.

10. Can you see the Hawaii skyline from the beach?

Absolutely. Some of the best views of the Honolulu and Waikīkī skyline are seen right from the beach. You can admire high-rises framed by calm ocean waves, with Diamond Head anchoring the scene. Maui and Kauaʻi also offer stunning skyline views dominated by mountains instead of buildings.

11. Is the Hawaii skyline good for photography?

Yes—Hawaii’s skyline is a dream for photographers. The blend of urban silhouettes, ocean reflections, volcanic backdrops, and colorful skies makes it one of the most photogenic skylines in the world. Sunrise and sunset are especially breathtaking.

12. What makes the Hawaii skyline meaningful beyond its beauty?

The skyline reflects Hawaii’s values: a balance between progress and preservation, culture and nature. It tells the story of islands shaped by volcanic forces, enriched by Hawaiian heritage, and guided by sustainable planning. Whether viewed at dawn, dusk, or from the ocean, the skyline symbolizes Hawaii’s harmony between city life and natural wonder.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

When people think of Hawai‘i, they often picture swaying palm trees, turquoise waters, and fragrant flowers. But nestled among the islands’ unique natural wonders is a remarkable bird that holds deep cultural and ecological significance—the Nēnē, or Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis). As Hawai‘i’s official state bird, the Nēnē symbolizes resilience, adaptation, and the importance of conservation in preserving the islands’ natural heritage.

The Nēnē is endemic to Hawai‘i, meaning it is found nowhere else on Earth. Believed to have evolved from the Canada goose thousands of years ago, these birds adapted to the islands’ volcanic landscapes, grasslands, and shrublands. Over time, they developed distinct features that set them apart from their ancestors.

One of the most fascinating adaptations is their feet. Unlike most geese, the Nēnē has partially webbed feet, which allow it to walk on rugged lava rock, climb slopes, and navigate dry grasslands. This adaptation reflects their transition from a primarily aquatic environment to a more terrestrial lifestyle in Hawai‘i’s unique terrain.

The Nēnē is a medium-sized goose, about 25 inches long with a wingspan of roughly three feet. It is easily recognized by its black face and crown, buff-colored cheeks, and strong barred patterns across its neck, which look almost like a necklace of grooves. The plumage blends beautifully into the volcanic landscapes of the islands, offering them natural camouflage.

Unlike other geese that are known for their loud honking, the Nēnē has a softer, more melodic call. These birds are primarily herbivores, feeding on native shrubs, grasses, and berries, particularly the fruit of the ‘ōhelo berry plant, which also holds significance in Hawaiian culture.

Nēnē are monogamous, and pairs often form strong, lifelong bonds. During the nesting season, which usually spans from October to March, females lay three to five eggs in ground nests hidden among vegetation. The goslings are able to walk and feed themselves within days of hatching, though they remain under the care and protection of their parents.

Despite its symbolic and ecological importance, the Nēnē came dangerously close to extinction in the 20th century. By the 1950s, fewer than 30 birds remained in the wild. Habitat destruction, hunting, and the introduction of predators such as mongoose, rats, and feral cats had decimated populations across the islands.

Recognizing the crisis, conservationists launched ambitious recovery programs. Captive breeding efforts, spearheaded in part by conservationists in Hawai‘i and abroad, played a pivotal role in saving the Nēnē. Birds raised in captivity were carefully reintroduced into protected areas across the islands, including national parks, wildlife refuges, and conservation lands.

Today, the Nēnē population has rebounded to over 3,000 individuals, with stable populations on Hawai‘i Island, Maui, Kaua‘i, and even reintroduction efforts on O‘ahu. While the bird is still listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, its recovery is often celebrated as one of the greatest conservation success stories in Hawai‘i.

For Native Hawaiians, the Nēnē has long held a place of cultural reverence. It is seen not only as a symbol of the islands but also as a living connection to the land (‘āina). Some traditions suggest the bird embodies qualities of endurance and adaptability—traits mirrored in the Hawaiian people themselves.

The bird’s name, “Nēnē,” is said to reflect its soft, gentle call. In Hawaiian culture, the naming of animals often connects to their spirit and behavior, highlighting a deep respect for the natural world.

When the Nēnē was officially designated the state bird of Hawai‘i in 1957, it became a powerful emblem of pride and identity. Its survival story is now tied not only to conservation biology but also to cultural renewal and education, reminding residents and visitors alike of the need to protect Hawai‘i’s fragile ecosystems.

If you’re visiting Hawai‘i and would like to see the Nēnē in its natural habitat, you’re in luck. National parks and reserves offer safe havens where these birds thrive. Some of the best places to encounter them include:

When observing these birds, it’s important to keep a respectful distance. Feeding Nēnē is strictly prohibited, as it can disrupt their natural diet and behavior. Responsible wildlife viewing ensures their continued survival and helps protect the delicate balance of Hawai‘i’s ecosystems.

The Nēnē’s story is more than just a tale of a bird brought back from the brink of extinction. It is a reminder of the interconnectedness of culture, conservation, and community. By saving the Nēnē, Hawai‘i has also safeguarded the integrity of its landscapes and preserved a vital link between people and place.

As Hawai‘i continues to face environmental challenges such as climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species, the survival of the Nēnē serves as both a beacon of hope and a call to action. Protecting this bird means protecting Hawai‘i itself.

1. What is the Nēnē, and why is it considered Hawaii’s state bird?

The Nēnē, or Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis), is the official state bird of Hawai‘i. It’s beloved for its cultural importance, resilience, and unique adaptations to the islands. Found nowhere else in the world, the Nēnē symbolizes Hawaii’s commitment to protecting its native wildlife and preserving its natural heritage.

2. Is the Nēnē found anywhere outside of Hawaii?

No. The Nēnē is endemic to Hawai‘i, meaning it exists only in the Hawaiian Islands. It evolved from the Canada goose thousands of years ago and adapted to Hawaii’s volcanic landscapes, grasslands, and shrublands. Its story is a powerful reminder of how isolated island ecosystems create one-of-a-kind species.

3. What makes the Nēnē different from other geese?

The Nēnē has several unique characteristics:

4. What does the Nēnē look like and how does it behave?

Nēnē are medium-sized geese with black heads, buff-colored cheeks, and distinctive striped neck feathers. They blend seamlessly into volcanic landscapes. They’re also:

5. How close did the Nēnē come to extinction?

In the 1950s, the Nēnē population dropped to fewer than 30 birds, putting the species on the brink of extinction. Habitat loss, hunting, and invasive predators such as mongoose and feral cats nearly wiped them out.

Thanks to dedicated captive breeding programs and reintroduction efforts, population numbers now exceed 3,000 birds—one of Hawaii’s greatest conservation success stories.

6. Why is the Nēnē important in Hawaiian culture?

The Nēnē holds deep cultural significance for Native Hawaiians. Its name comes from its gentle vocalizations, and the bird is often associated with adaptability, endurance, and a strong connection to the ʻāina (land). When Hawai‘i designated the Nēnē as its state bird in 1957, it became a symbol of pride, identity, and the importance of caring for the land and its wildlife.

7. Where can I see the Nēnē in Hawaii today?

If you’re visiting Hawai‘i, you can spot Nēnē in several protected natural areas:

8. Why is it important not to feed Nēnē?

Feeding Nēnē may seem kind, but it harms them. Human food disrupts their natural diet, increases dependency, and can cause dangerous behavior near roads or humans. Feeding wildlife also violates federal and state regulations. The best way to help Nēnē is by viewing them responsibly and supporting conservation efforts.

9. How did conservationists help save the Nēnē?

Conservationists used a combination of:

10. Why does the Nēnē matter to Hawaii’s ecosystem?

As a native herbivore, the Nēnē plays a role in seed dispersal, vegetation control, and maintaining healthy grassland ecosystems. Its survival supports the overall balance of Hawaii’s fragile natural environment. Saving the Nēnē also helps preserve countless native plant species and habitats that depend on responsible stewardship.

11. What does the recovery of the Nēnē teach us about conservation?

The Nēnē’s comeback shows that community support, scientific research, and cultural awareness can make a real difference in restoring endangered species. It also highlights the importance of protecting Hawaii’s ecosystems from modern threats like invasive species and climate change.

12. Is the Nēnē friendly or safe to approach?

Nēnē are gentle birds but should never be approached or touched. They are protected by law, and human interaction can stress them or disrupt their behavior. Observe from a respectful distance, use your camera’s zoom, and allow them to go about their natural activities undisturbed.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

The Hawaiian Islands are not only breathtaking landscapes of volcanic peaks, lush rainforests, and endless coastlines; they are also lands alive with stories, chants, and legends passed down for generations. These mo‘olelo (traditional stories) are woven deeply into the fabric of Hawaiian identity, explaining natural phenomena, teaching cultural values, and honoring the sacred relationship between people and the land.

One of the most celebrated figures in Hawaiian mythology is the demigod Māui. Known across Polynesia in many forms, Māui is remembered as a trickster, a hero, and a benefactor of humanity. In Hawaii, his legends are especially tied to the island of Maui, which bears his name. To explore the island without learning the stories of this demigod would be to miss an essential part of its soul.

Māui is not unique to Hawaii—his stories are found throughout Polynesia, from Tahiti to Samoa to Aotearoa (New Zealand). Yet, while the details shift with each culture, he consistently embodies the traits of intelligence, resourcefulness, and mischief. He is often seen as a kupua, a supernatural being with both divine and human qualities, who uses cleverness and courage to challenge nature itself.

In Hawaii, Māui is not considered one of the four primary gods (akua)—Kāne, Kū, Lono, and Kanaloa—but rather a heroic demigod whose actions brought great benefits to humankind. His tales are told not just as entertainment, but as teaching stories filled with lessons about perseverance, balance, and respect for the forces of the natural world.

Perhaps the most famous Hawaiian legend of Māui tells of his battle with the sun. In ancient times, the sun raced across the sky, leaving days too short for people to grow crops, dry their kapa (bark cloth), or prepare food. Māui, determined to help his mother and his people, climbed to the summit of Haleakalā, the massive volcano that dominates the island of Maui.

There, he lay in wait until dawn, crafting ropes from coconut fiber and lashing them with his great strength. When the sun appeared, Māui snared its rays and refused to release them until the sun agreed to slow its journey. The sun relented, granting longer days and blessing humanity with time to live and thrive. Today, visitors to Haleakalā National Park watch the sunrise and recall this powerful story, a reminder of Māui’s triumph and the island’s spiritual depth.

Another story tells of Māui’s magical fishhook, called Manaiakalani. With it, Māui pulled great land masses from the depths of the ocean. In some traditions, it is said that he fished up islands themselves. In Hawaiian legend, this reflects the volcanic creation of new lands rising from beneath the Pacific, linking myth with the geologic truth of the islands’ origins.

Māui’s ingenuity was not limited to the sun and sea. In one tale, he captured the powerful winds that made sailing dangerous. By taming these forces, he allowed Polynesian navigators to voyage more safely across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, ensuring survival and expansion. This legend resonates with Hawaii’s deep voyaging traditions and the revival of navigation by stars, currents, and winds in modern times through groups such as the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Māui’s feats are more than just fantastical tales. They symbolize humanity’s relationship with the natural world and highlight values central to Hawaiian culture:

In this way, Māui reflects the Hawaiian concept of pono—living in balance and righteousness with the world around you.

The island of Maui itself is said to be named after the demigod. In the kumulipo (Creation Chant) it is told that Māui’s father, 'Akalana, named the island in his honor. Others suggest that the island’s very shape, dominated by Haleakalā’s vast shield volcano, recalls the legends of Māui’s great deeds.

For Hawaiians, this connection is more than symbolic. The island and the demigod are spiritually tied, reminding residents and visitors that Maui is not only a place of natural beauty but also a sacred landscape shaped by story and tradition.

Though centuries have passed, Māui’s stories remain alive. They are shared through oli (chants), hula (dance), and mo‘olelo (oral traditions), connecting each new generation to the wisdom of the past. Cultural practitioners continue to honor these legends as living knowledge, not relics of history.

For visitors, learning about Māui is a way to deepen their experience of the island. Watching the sunrise at Haleakalā, paddling in the ocean, or simply walking the land becomes more meaningful when one understands that these places are alive with history, myth, and spirit.

Māui, the demigod of the Hawaiian island of Maui, embodies the enduring spirit of ingenuity, courage, and connection to nature. His legends—snaring the sun, fishing up islands, and taming the winds—are not only stories of heroism but also reflections of the Hawaiian worldview: that humanity must live in balance with the powerful forces that shape our world.

The island of Maui, bearing his name, is both a geographical wonder and a cultural treasure. To explore it is to step into a landscape where myth and reality blend, where every sunrise recalls an ancient victory, and where the legacy of Māui continues to inspire those who walk upon his island.

1. Who is Māui in Hawaiian mythology?

Māui is a heroic demigod celebrated across the Hawaiian Islands for his cleverness, bravery, and contributions to humanity. Although not one of the four major Hawaiian gods, Māui appears in countless mo‘olelo (traditional stories) as a kupua—someone with both divine and human qualities. His feats often help people, such as slowing the sun, controlling the winds, and raising land from the ocean. These Hawaiian legends highlight values of resourcefulness, respect for nature, and the importance of living in balance.

2. How is Māui connected to the island of Maui?

The island of Maui is said to be named after the demigod. Some stories say Māui’s mother, Hina, gave the island his name; others say the island’s shape and rugged volcanic features reflect his legendary deeds. For many Hawaiians, this connection is more than symbolic—the island and the hero share spiritual importance. Visiting Maui while learning about Māui deepens your understanding of the land, culture, and history woven into the island.

3. Is Māui found only in Hawaiian stories?

No—Māui is a prominent figure throughout Polynesia. His legends appear in places such as Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, and Aotearoa (New Zealand). While each region tells different versions of his stories, Māui consistently appears as a clever, mischievous, and heroic figure. In Hawaii specifically, the tales emphasize his ability to help humanity and teach lessons about perseverance and harmony with nature.

4. What is the story of Māui snaring the sun on Haleakalā?

One of the most famous Hawaiian legends tells how Māui slowed the sun to give people longer days. According to the story, days were once too short for cooking, fishing, and kapa-making, so Māui climbed to the summit of Haleakalā with strong ropes made from coconut fiber. When the sun rose, he snared its rays and refused to release them until the sun agreed to move more slowly. Today, watching sunrise at Haleakalā National Park is a powerful reminder of this legendary feat.

5. What is Māui’s magical fishhook, and what did he do with it?

Māui’s fishhook, Manaiakalani, is central to one of his most famous exploits. Hawaiian legends say Māui used the fishhook to pull land from the depths of the ocean. In some Polynesian traditions, he fished up islands themselves. This myth beautifully mirrors Hawaii’s real volcanic origins—new land rising from the sea—blending science with storytelling and cultural meaning.

6. What does the legend of Māui controlling the winds teach us?

In this lesser-known story, Māui captures and tames powerful winds that once made ocean voyaging difficult and dangerous. By controlling these winds, he allowed ancient Polynesian navigators to travel more safely across vast distances. This legend highlights Hawaii’s deep ocean-voyaging heritage and emphasizes how Māui symbolizes guidance, navigation, and human connection to natural forces.

7. What values or lessons do Māui’s legends teach?

The stories of Māui illustrate several core Hawaiian values:

These lessons continue to guide Hawaiian cultural practices and storytelling today.

8. Why are Hawaiian legends and mo‘olelo so important?

Hawaiian mo‘olelo are more than myths—they are cultural maps, teaching tools, and historical records that explain natural phenomena, honor ancestors, and preserve knowledge. These stories connect Hawaiians to their land, values, and identity. Learning these legends helps visitors appreciate the islands not just as destinations, but as living cultural landscapes filled with meaning and history.

9. How is Māui’s legacy preserved in Hawaii today?

Māui’s stories are kept alive through oli (chants), hula (dance), and oral storytelling traditions. Cultural practitioners, educators, and families continue to share these legends as living knowledge. When visitors explore places like Haleakalā, paddle along the coast, or walk the land, they are stepping into spaces shaped by both volcanic history and the stories of Māui that still echo across the island.

10. Do these legends add meaning to visiting Maui as a tourist?

Absolutely. Learning about Māui before or during your trip adds depth to every experience—sunrise at Haleakalā becomes a connection to an ancient legend, island landscapes become reminders of volcanic creation stories, and even the ocean winds feel tied to ancestral navigation. Understanding the demigod’s role in Hawaiian culture enriches your visit and helps you appreciate Maui as a sacred, storied island.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Hawaiʻi is often celebrated for its beaches, volcanoes, and lush rainforests, but the islands are also home to one of the most fascinating bird communities in the world. Due to their isolation in the middle of the Pacific, Hawaiʻi’s birds evolved in unique ways, creating species found nowhere else on Earth. From jewel-toned honeycreepers to soaring seabirds, the avifauna of Hawaiʻi is as diverse as it is fragile.

This blog explores the rich world of Hawaiian birds—their history, ecological role, cultural importance, and the ongoing efforts to protect them.

Roughly five million years ago, a single finch-like bird made its way to the Hawaiian Islands. Over millennia, this ancestor gave rise to an astonishing radiation of species known today as the Hawaiian honeycreepers. With beaks adapted to specific foods—from nectar to seeds to insects—these birds became a striking example of adaptive evolution. Their plumage is equally remarkable, ranging from bright reds and yellows to subtle greens and browns.

Unfortunately, many of these species are now extinct, and many of the survivors are critically endangered. Yet those that remain provide a living window into evolution’s creativity.

The ʻiʻiwi is perhaps the most recognizable of Hawaiʻi’s native birds. With scarlet feathers, black wings, and a gracefully curved bill, it feeds primarily on the nectar of native ʻōhiʻa lehua blossoms. Once widespread across all islands, the ʻiʻiwi is now mostly found at higher elevations, where mosquitoes that carry avian malaria are less common.

Another nectar-feeding honeycreeper, the ʻapapane thrives in ʻōhiʻa forests and is known for its loud, complex song. Though still relatively common, it plays an important ecological role as a pollinator.

Resilient and adaptable, the Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi is one of the few native birds showing resistance to avian malaria. Its olive-yellow feathers and versatility in feeding—nectar, insects, and fruits—have helped it persist even as other species decline.

Deeply significant in Hawaiian culture, the ʻalalā was once considered a guardian spirit and messenger. Sadly, it became extinct in the wild in the early 2000s, though captive breeding and reintroduction programs are ongoing. The ʻalalā is highly intelligent, known for using tools and complex vocalizations.

The only hawk native to Hawaiʻi, the ʻio is found only on the Big Island. Revered in Hawaiian tradition as an embodiment of royalty and a messenger of the gods, the ʻio is a powerful predator that soars over forests and open fields alike.

While forest birds often capture attention, Hawaiʻi’s seabirds are equally extraordinary. The islands provide nesting grounds for millions of seabirds that roam the Pacific.

Not all birds in Hawaiʻi are native. Humans have introduced species such as the common myna, zebra dove, and house sparrow, which are now among the most commonly seen in towns and cities. While these birds add to the islands’ avian diversity, some compete with native species for food and nesting sites.

For Native Hawaiians, birds are deeply intertwined with tradition, art, and spirituality. The vibrant feathers of species like the ʻiʻiwi and ʻōʻō were once used to create royal cloaks and helmets, symbols of mana (spiritual power) and authority. Birds also appear in chants, legends, and proverbs, serving as guides, protectors, and omens.

The ʻio, for instance, was seen as a protector of chiefs, while the ʻalalā was viewed as a voice of the forest, bridging the human and spiritual realms.

Hawaiʻi is often called the “extinction capital of the world.” Since human arrival, more than half of the islands’ bird species have vanished. The primary threats today include:

Conservation efforts are underway to protect the remaining species. Strategies include mosquito control programs, captive breeding and reintroduction of endangered birds, and habitat restoration. Organizations and agencies are working tirelessly to ensure that Hawaiʻi’s unique birds continue to thrive for generations to come.

The birds of Hawaiʻi are more than just beautiful creatures—they are storytellers of evolution, stewards of native ecosystems, and cultural treasures. Whether watching an ʻiʻiwi dart among ʻōhiʻa blossoms, listening to the haunting call of a shearwater, or spotting an ʻio soaring above the Big Island, one cannot help but feel a deep connection to the land and its living heritage.

Protecting these birds is not only about conservation—it is about preserving the soul of Hawaiʻi itself.

1. Why are Hawaiian birds so unique compared to birds elsewhere in the world?

Hawaiian birds are incredibly unique because the islands’ remote location allowed species to evolve in isolation for millions of years. A single finch-like ancestor led to the creation of the famous Hawaiian honeycreepers—birds with dramatically different beak shapes, colors, and feeding habits. Many Hawaiian birds are endemic, meaning they exist nowhere else on Earth, making them some of the rarest and most remarkable birds on the planet.

2. What are Hawaiian honeycreepers, and why are they so important?

Hawaiian honeycreepers are a group of native birds that evolved from one common ancestor around five million years ago. Through adaptive evolution, these birds developed specialized beaks to eat nectar, seeds, insects, and fruits. Their vibrant colors—from reds and yellows to greens—make them some of the most striking birds in Hawaiʻi. Honeycreepers are essential pollinators in native forests and are a living example of evolution’s creativity.

3. Which native Hawaiian birds should visitors look out for?

Some of the most notable native Hawaiian birds include:

These species represent Hawaiʻi’s natural heritage and ecological diversity.

4. What seabirds and shorebirds can be found in Hawaiʻi?

Hawaiʻi is home to impressive seabirds and waterbirds, including:

Many seabirds nest in colonies on remote islands or steep cliffs, making Hawaiʻi a crucial habitat for Pacific bird populations.

5. Are all the birds in Hawaiʻi native?

No—many birds in Hawaiʻi are introduced species brought by humans over the past 200 years. Common urban birds like mynas, zebra doves, and house sparrows are not native. While they add to the visual diversity of the islands, some introduced species compete with native birds for food and nesting areas, creating conservation challenges.

6. Why are so many Hawaiian birds endangered or extinct?

Hawaiʻi is known as the extinction capital of the world, and sadly, many native birds have disappeared. The main threats include:

These factors create difficult conditions for native species, especially honeycreepers that rely on high-elevation forests.

7. What conservation efforts are being made to protect Hawaiian birds?

Conservation in Hawaiʻi is extensive and ongoing. Efforts include:

8. What role do birds play in Hawaiian culture and tradition?

Birds are deeply woven into Hawaiian culture. Feathers from birds like the ʻiʻiwi and ʻōʻō were once used to create royal cloaks and helmets, representing mana (spiritual power). Birds also appear in Hawaiian chants, mythology, and proverbs. For example:

Birds symbolize connection, protection, and the natural balance that is central to Hawaiian identity.

9. Where can visitors see native Hawaiian birds in the wild?

Some of the best places to see native Hawaiian birds include:

These areas protect native forests where honeycreepers and other endemic species still thrive.

10. Why is protecting Hawaiian birds so important?

Protecting Hawaiian birds means preserving Hawaiʻi’s ecology, culture, and history. These birds pollinate forests, control insects, and reflect the islands’ evolutionary heritage. They carry cultural meaning and connect Hawaiians to their ancestral past. Saving them is about more than conservation—it’s about keeping the spirit and identity of Hawaiʻi alive for future generations.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

The Hawaiian Islands are known worldwide for their beauty, culture, and aloha spirit—but behind each island’s name lies a story rooted in history, language, and tradition. Some names are tied to Hawaiian gods and legends, others to early explorers and migrations, and still others to natural features that inspired their titles. Understanding how Hawai‘i’s islands got their names offers a deeper appreciation for the archipelago’s cultural and linguistic heritage.

The largest island in the chain, Hawai‘i Island, shares its name with the entire state. According to Hawaiian tradition, the name comes from Hawai‘iloa, a legendary Polynesian navigator credited with discovering the islands. Some oral histories suggest Hawai‘iloa named the island after himself, while others connect the word Hawai‘i to the ancestral homeland of the Polynesians, Hawaiki, a place referenced in oral traditions across the Pacific.

Because of its size, Hawai‘i Island is often called “The Big Island” to avoid confusion with the state name. Its vast landscapes, from active volcanoes to snow-capped Mauna Kea, make it a fitting bearer of the archipelago’s central name.

Learn more about Hawai‘i Island

The island of Maui is named after the demigod Māui, a heroic figure common in Polynesian mythology. In Hawaiian lore, Māui is famous for his strength and cleverness—he is said to have fished the islands out of the sea and slowed the sun to give humanity longer days.

Some traditions say the island was named by the navigator Hawai‘iloa in honor of his son, who was named after the demigod. The association between the island and this cultural hero makes Maui a land of legendary stature.

Explore Maui’s history

O‘ahu translates to “The Gathering Place,” though its exact origins are less clear than some other islands. The name appears in Hawaiian oral traditions and songs, but no definitive explanation exists. Some suggest that O‘ahu was named by Hawai‘iloa after one of his relatives.

True to its title, O‘ahu has always been a gathering place—it is home to Honolulu, the state capital, and the majority of Hawai‘i’s population today. With historic sites like Pearl Harbor and cultural landmarks such as ʻIolani Palace, O‘ahu remains a center of both ancient and modern Hawaiian life.

More on O‘ahu’s culture

Kaua‘i, often called the “Garden Island,” may derive its name from the Hawaiian word kau (to place) and a‘i (to eat). Some interpret this as “a place around the neck,” referencing the island’s shape. Others link it to legends of Hawai‘iloa, who is said to have named the island after his son.

Kaua‘i is the oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands geologically, and its name reflects a deep connection to family and tradition. Its lush mountains and valleys give it a timeless, almost mystical quality, matching the poetic beauty of its name.

Discover Kaua‘i

Known as the “Friendly Isle,” Moloka‘i is deeply tied to Hawaiian culture. It is home to Kalaupapa, the historic settlement where Saint Damien and Saint Marianne cared for people with Hansen’s disease (leprosy), and it is regarded as a place where traditional Hawaiian practices remain strong.

Learn more about Moloka‘i

Lāna‘i is often called the “Pineapple Isle,” but its traditional name is said to mean “day of conquest.” According to legend, the island was once inhabited by spirits until a Maui chief’s son, Kaululā‘au, banished them and claimed the island for people. Another interpretation ties the name to lā (day) and na‘i (conquer), reflecting the conquest of these spirits.

In modern times, Lāna‘i was famous for its pineapple plantations, once producing most of the world’s pineapples. Today it is known for its quiet landscapes and luxury resorts.

Explore Lāna‘i

The privately owned island of Ni‘ihau has a name with uncertain origins. Some suggest it means “snatched away,” possibly referring to its creation in myth when it was pulled from the sea. Others connect it to words meaning “withered” or “dry,” reflecting its arid climate.

Ni‘ihau is unique as the “Forbidden Island,” closed to most visitors, and it is one of the last places where Hawaiian is spoken as the primary language.

Learn more about Ni‘ihau

The smallest of the main islands, Kaho‘olawe, is named for its natural environment. Known as "The Target Isle" as it was used as a bombing target practice for the United States military during World War II.

Kaho‘olawe has a turbulent modern history, as it was used by the U.S. military for bombing practice during World War II and afterward. Today, it is uninhabited and managed by the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission, dedicated to cultural and ecological restoration.

Learn about Kaho‘olawe

The names of Hawai‘i’s islands are not just labels—they are living reminders of legends, family ties, and natural features. They connect modern residents and visitors to the islands’ ancient past and help preserve the Hawaiian language and worldview.

When you say Maui or Kaua‘i, you are invoking the names of gods, ancestors, or poetic descriptions of the land itself. Recognizing the origins of these names adds depth to any journey across Hawai‘i and reinforces the importance of respecting the culture that continues to thrive here.

1. How did the Hawaiian Islands get their names?

Each Hawaiian island’s name reflects a mix of legend, language, history, and geography. Some names come from Hawaiian gods and demigods, such as Maui; others come from ancient Polynesian navigators like Hawai‘iloa; and some connect to natural features or poetic descriptions. These names preserve Hawai‘i’s ancestral stories and offer deeper insight into the culture and worldview of Native Hawaiians.

2. Why is Hawai‘i Island called “The Big Island”?

Hawai‘i Island shares its name with the entire state, so people call it “The Big Island” to avoid confusion. According to tradition, the island’s name comes from Hawai‘iloa, a legendary navigator who discovered the archipelago. Some stories say he named the island after himself, while others link the name to Hawaiki, the ancestral homeland referenced across Polynesia.

3. Why is the island of Maui named after the demigod Māui?

Maui is named after Māui, the iconic Polynesian demigod known for slowing the sun and pulling islands from the sea. Some legends say Hawai‘iloa named the island after his son, who was named in honor of the demigod. This connection gives the Valley Isle a strong tie to myth and heroic tradition.

4. What does the name O‘ahu mean?

O‘ahu is often translated as “The Gathering Place.” While its exact linguistic origin isn’t fully documented, the name appears frequently in chants, oral histories, and ancient stories. Fittingly, O‘ahu is still the “gathering place” today as the home of Honolulu, Waikīkī, and the majority of Hawai‘i’s population.

5. Where does the name Kaua‘i come from?

The origin of Kaua‘i is not completely certain. One interpretation links its name to kau (to place) and a‘i (to eat), while another ties it to Hawai‘iloa’s son. As the oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands, Kaua‘i’s poetic name reflects its deep roots in family tradition, age-old legends, and the island’s lush, mystical landscapes.

6. What is the meaning behind the name Moloka‘i?

Moloka‘i, known as “The Friendly Isle,” holds a strong cultural and spiritual history. Its name’s origin is debated, but the island itself remains closely tied to Hawaiian traditions, including storytelling, farming, fishing, and historical sites like Kalaupapa, where Saint Damien and Saint Marianne cared for people with Hansen’s disease.

7. Why is Lāna‘i called “the Pineapple Isle,” and what does its name originally mean?

Lāna‘i earned the nickname “The Pineapple Isle” thanks to its once-massive pineapple plantations. Traditionally, however, the name Lāna‘i is said to mean “day of conquest.” Legend says a Maui chief’s son, Kaululā‘au, drove away spirits from the island, making it suitable for human settlement.

8. What is the meaning of Ni‘ihau’s name?

The exact meaning of Ni‘ihau is uncertain. Some legends interpret it as “snatched away,” referencing mythological creation stories, while others translate it as “withered” or “dry,” reflecting its arid environment. Today, Ni‘ihau is known as “The Forbidden Island,” privately owned and known for its preservation of Hawaiian language and culture.

9. Why is Kaho‘olawe considered sacred, and how did it get its name?

Kaho‘olawe’s name is often linked to its natural environment, with some translations meaning “the carrying away” or connected to storms and dryness. It is considered sacred by Native Hawaiians and has been the focus of significant cultural and ecological restoration after decades of military use. Today, it is uninhabited and protected by the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission.

10. Why do the names of Hawai‘i’s islands matter so much?

The names of Hawai‘i’s islands are more than geographic labels—they are living reflections of culture, language, genealogy, and spirituality. Knowing their meanings helps visitors appreciate the islands on a deeper level and encourages respect for Hawaiian traditions. When you say names like Maui or Kaua‘i, you’re speaking words rooted in ancient stories and cultural identity.

11. How can learning the meanings of Hawaiian island names enhance my visit?

Understanding each island’s name deepens your connection to the places you explore. Whether visiting Maui’s legendary landscapes, Kaua‘i’s ancient valleys, or O‘ahu’s historic sites, the stories behind the names enrich your experience and help you travel with greater respect for Hawai‘i’s culture and heritage.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

When people think of Hawai‘i, the word Aloha often comes to mind. Tourists hear it upon arrival and departure, see it printed on souvenirs, and may even adopt it as a casual greeting. But to those who live in Hawai‘i or understand Hawaiian culture, Aloha is much more than a word—it is a way of life, a profound philosophy, and a spiritual connection to others and to the land.

In its most basic usage, Aloha means both "hello" and "goodbye," but this simple translation does not capture the essence of the word. Rooted in Native Hawaiian values, Aloha expresses love, compassion, mercy, respect, and unity. It is a sacred word that reflects the deep cultural and spiritual beliefs of the Hawaiian people.

The word Aloha is composed of two parts: "Alo" meaning presence, front, or face, and "ha" meaning breath of life. When said in its full context, Aloha can be interpreted as “the presence of divine breath” or “to share the breath of life.” In ancient Hawai‘i, the traditional greeting involved touching foreheads and exchanging a breath (honi), symbolizing this shared life force. Saying Aloha isn't just a polite phrase; it's an acknowledgment of the sacred life energy that flows through and connects all beings.

Native Hawaiian scholar and cultural practitioners have long emphasized that Aloha is a guiding principle. It is an ethical code of conduct built on mutual respect and care for one another. The Aloha Spirit—a term frequently used in Hawai‘i—is about living in harmony with yourself, with others, and with nature. It encourages kindness, patience, and understanding, even in difficult situations.

The Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s helped revive many traditional values, including the philosophy of Aloha. Today, many Hawaiian elders (kupuna) and educators pass this teaching on, emphasizing that living with Aloha is an ongoing practice of humility (ha‘aha‘a), harmony (lokahi), and compassion (aloha kekahi i kekahi—love one another).

Interestingly, Hawai‘i is the only U.S. state with a law explicitly recognizing a cultural value. In Section 5-7.5 of the Hawai‘i Revised Statutes, the Aloha Spirit is formally recognized as a guiding principle for public officials. This law encourages government leaders and citizens alike to treat one another with care, respect, and love, using Aloha as a basis for decision-making and daily interaction.

Here’s an excerpt from the statute:

“Aloha is more than a word of greeting or farewell or a salutation. Aloha means mutual regard and affection and extends warmth in caring with no obligation in return.”

This demonstrates just how deeply rooted the concept of Aloha is in the social fabric of the islands.

Another important dimension of Aloha is its relationship with nature, especially the land—ʻāina. In Hawaiian belief, the land is not a resource to be exploited, but a family member to be cared for and respected. The phrase Aloha ʻĀina means “love of the land,” and it encapsulates a deep sense of responsibility and stewardship for Hawai‘i’s natural environment.

Many Hawaiian activists and cultural practitioners use Aloha ʻĀina to express their commitment to protecting sacred spaces, preserving ecosystems, and fighting for the sovereignty of the land. Whether it's resisting overdevelopment, advocating for clean water, or restoring native plants, these efforts are grounded in the spiritual and cultural imperative of Aloha.

To live with Aloha means practicing it daily—not only with friends and family, but also with strangers, coworkers, and even adversaries. It is being mindful of how one’s actions affect others, choosing empathy over judgment, and approaching life with gratitude.

Simple acts like:

…are all ways of embodying Aloha.

And it’s not limited to those who live in Hawai‘i. The principles of Aloha can be practiced by anyone, anywhere. In a world often driven by division and competition, Aloha offers a powerful reminder of our shared humanity.

Aloha is not just a word; it's a worldview. It calls us to be present, to act with compassion, and to live in alignment with nature and each other. Whether you're visiting Hawai‘i for the first time or have lived there your whole life, understanding the deeper meaning of Aloha can enrich your experience and connection to this special place.

Let’s not just say Aloha—let’s live it.

If you enjoyed learning about Aloha, consider exploring other core Hawaiian values like ʻohana (family), pono (righteousness), and malama (to care for). Each of these values interweaves with Aloha to create the spiritual and cultural richness that makes Hawai‘i truly unique.

1. What does the word Aloha actually mean in Hawaiian?

Aloha is often translated as “hello” and “goodbye,” but its true meaning goes much deeper. In Hawaiian culture, Aloha represents love, compassion, respect, kindness, and connection. Linguistically, “Alo” means presence or face, and “ha” means breath of life—so Aloha can be understood as “the presence of divine breath.” It reflects the Hawaiian belief that we are all connected through shared life energy.

2. Why is Aloha considered more than just a greeting?

Aloha is much more than a casual phrase—it is a cultural philosophy and way of life. For Native Hawaiians, Aloha is a guiding principle rooted in compassion, humility, harmony, and mutual respect. It’s a reminder to treat others with kindness and to be mindful of how one’s actions impact the world. Living with Aloha means approaching life with gratitude, patience, and empathy every day.

3. What is the traditional Hawaiian greeting involving breath?

The traditional greeting is called honi, where two people touch foreheads and noses to exchange a shared breath, or ha. This practice symbolizes unity, respect, and the acknowledgment of each other’s life force. Honi reflects the deeper meaning of Aloha—recognizing the sacred breath that connects all living beings.

4. What is the “Aloha Spirit,” and why is it important?

The Aloha Spirit is the cultural value system behind the word Aloha. It encourages living with openness, kindness, humility (haʻahaʻa), harmony (lokahi), and love for others (aloha kekahi i kekahi). It’s about choosing compassion even in difficult situations. The Aloha Spirit shapes how people interact in Hawai‘i, making the islands renowned for warmth, generosity, and peaceful living.

5. Is the Aloha Spirit really written into Hawaii state law?

Yes! Hawai‘i is the only U.S. state with a law recognizing a cultural value. In Hawai‘i Revised Statutes Section 5-7.5, the Aloha Spirit is formally acknowledged as a guiding principle for public officials and government workers. The law states that Aloha means mutual regard, affection, and warm caring without expectation of return. This highlights how deeply Aloha is embedded in everyday life and governance.

6. What does Aloha ʻĀina mean?

Aloha ʻĀina translates to “love of the land.” In Hawaiian culture, the land—ʻāina—is not a resource but a family member to be respected and protected. Aloha ʻĀina expresses a deep responsibility to care for nature, safeguard sacred places, and preserve Hawai‘i’s ecosystems. It also ties to cultural movements advocating sovereignty, environmental justice, and sustainable stewardship.

7. How can visitors to Hawai‘i live with Aloha during their stay?

Visitors can embrace Aloha by practicing kindness, respecting local culture, and caring for the land. Simple actions include:

8. Can people outside of Hawai‘i practice Aloha in their daily lives?

Absolutely. Aloha is universal. Anyone, anywhere can live with Aloha by choosing patience over frustration, empathy over judgment, gratitude over entitlement, and respect over conflict. Aloha is a reminder that human connection, kindness, and compassion make the world better no matter where you are.

9. How does Aloha relate to Hawaiian cultural identity today?

Aloha remains a cornerstone of Hawaiian identity. It influences relationships, traditions, spirituality, and community values. Through language revitalization, cultural education, and the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, the deeper meaning of Aloha continues to thrive. For many, Aloha represents both cultural pride and a spiritual responsibility to care for people and place.

10. Why is understanding the true meaning of Aloha important for visitors?