The Hawaiian hawk—known in Hawaiian as the ʻIo—is one of Hawaiʻi’s most iconic birds of prey and a powerful symbol of royalty, protection, and spiritual guidance. Found only in Hawaiʻi, primarily on the Big Island, this remarkable raptor is an irreplaceable part of the islands’ natural heritage. Its story blends ecology, culture, resilience, and the ongoing need for conservation.

Though once widespread across multiple islands, today the Hawaiian hawk persists mainly on Hawaiʻi Island. Its limited range and cultural significance make it one of the most unique birds in the world—and a living reminder of the deep connection between Native Hawaiian traditions and the islands’ native wildlife.

In this blog, we explore the origins, behaviors, cultural role, and importance of preserving this extraordinary endemic species.

The Hawaiian hawk (Buteo solitarius) is endemic to Hawaiʻi, meaning it evolved here and exists naturally nowhere else on the planet. Scientists believe the ancestors of the Hawaiian hawk arrived thousands of years ago and gradually adapted to the islands’ forests, climate, and prey.

These adaptations led to the development of traits that distinguish the Hawaiian hawk from continental hawks, including:

This ecological specialization is part of what makes Hawaiian wildlife so impressive—and so vulnerable. When a species evolves in isolation, it often becomes deeply dependent on the landscapes and ecosystems of its home. For the Hawaiian hawk, that home is primarily the forests of Hawaiʻi Island.

The Hawaiian hawk may not be large compared to mainland raptors, but it carries a powerful presence. Adults typically measure around 18 to 20 inches long with a wingspan of approximately 40 inches. The species displays two distinct color phases:

One of the most distinctive behaviors of the Hawaiian hawk is its piercing, high-pitched call, often described as sounding like “eee-oh,” which likely inspired the name ʻIo.

Unlike many specialized hawks, the Hawaiian hawk is an opportunistic predator. Over centuries, it adapted to hunt native birds, insects, and larger invertebrates. After the introduction of non-native animals like rats and mongoose, the hawk expanded its diet—an adaptability that likely helped keep the species alive despite major environmental changes.

Breeding season runs from March through September, when pairs become highly territorial. They build nests high in native trees, where a single chick is raised each year. Known for their dedicated parental care, both male and female hawks share responsibilities in feeding and protecting their young.

In Native Hawaiian culture, the ʻIo is a bird of aliʻi (royalty) and is associated with:

For many Native Hawaiians, seeing a Hawaiian hawk soaring overhead is considered a sign of blessing or guidance. The bird appears in chants, legends, and place names, further solidifying its role in Hawaiian identity.

Its cultural significance also played a role in shaping conservation efforts, as community groups and cultural practitioners have advocated strongly for protecting the species and its habitat.

Though the Hawaiian hawk was removed from the U.S. Endangered Species List in 2020, conservationists continue to monitor it closely. Its limited range makes it particularly vulnerable to:

Ongoing conservation initiatives include reforestation, habitat protection, and long-term population monitoring. Maintaining the species’ stability is essential not only for ecological balance but also for preserving its cultural significance.

The Hawaiian hawk is more than a rare island raptor—it is a symbol of Hawaiʻi’s natural resilience and cultural richness. As one of the few remaining native birds of prey, its continued survival is vital to:

Protecting the Hawaiian hawk means protecting a piece of Hawaiʻi’s identity.

1. What is the Hawaiian hawk?

The Hawaiian hawk, or ʻIo, is an endemic bird of prey found only in Hawaiʻi, known for its distinct call, two color phases, and powerful cultural significance.

2. Why is the Hawaiian hawk endemic to Hawaiʻi?

The species evolved in complete isolation over thousands of years, adapting uniquely to Hawaiʻi’s forests, climate, and prey, resulting in a raptor found nowhere else in the world.

3. Where can you see the Hawaiian hawk?

The Hawaiian hawk is seen almost exclusively on Hawaiʻi Island, especially in forested areas, open fields, and high-elevation regions.

4. Is the Hawaiian hawk endangered?

The species was delisted in 2020, but because it lives on only one island, it remains vulnerable and is continually monitored by conservation organizations.

5. What does the Hawaiian hawk symbolize in Hawaiian culture?

It represents royalty, protection, spiritual guidance, and the god Kū, making it one of the most culturally significant birds in Hawaiʻi.

6. What do Hawaiian hawks eat?

They are opportunistic hunters, feeding on birds, insects, rodents, and occasionally carrion.

7. Why is protecting the Hawaiian hawk important?

The species plays a crucial ecological role, represents native Hawaiian heritage, and embodies the unique biodiversity of the islands.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

When visitors first arrive in Hawaiʻi, they expect to see tropical birds, sea turtles, and vibrant marine life—but many are surprised when they spot a quick, slender creature darting across the road. That animal is the mongoose, one of the most misunderstood and impactful invasive species in Hawaiʻi. Although they may look harmless at first glance, the story of the mongoose reveals a complex ecological history deeply tied to the islands’ delicate native wildlife.

Understanding the mongoose—why it was introduced, how it behaves, and what role it plays today—is essential for anyone who wants to learn more about Hawaiʻi’s environment and the challenges conservationists face.

The mongoose (specifically the small Indian mongoose, Herpestes auropunctatus) was introduced to Hawaiʻi in the late 1800s. At the time, sugarcane plantations dominated the islands’ economy. Planters struggled with rats destroying crops, so they sought a biological solution: import mongooses, which were known to prey on rodents in other parts of the world.

In 1883, mongooses were shipped from Jamaica to Hawaiʻi and released on several islands to help control rat populations. However, this plan had one fatal flaw—rats are primarily nocturnal, while mongooses are diurnal. The two species were rarely active at the same time, so the mongoose did very little to reduce rat numbers.

Instead, they turned their attention to something else: native birds, eggs, small mammals, and reptiles.

Once in the wild, mongooses reproduced quickly and spread across the islands. Today they are found on:

They are not found on Kauaʻi, where strict prevention efforts continue because of the island’s rich bird populations.

Mongooses pose a significant threat to native Hawaiian wildlife because:

They Eat Ground-Nesting Birds

Many of Hawaiʻi’s most vulnerable species, including the Hawaiian goose (Nēnē), ʻuaʻu (Hawaiian petrel), and seabirds, lay eggs on or near the ground. Mongooses raid nests and drastically reduce breeding success.

They Prey on Endangered Species

Small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and bird chicks are all within their diet.

They Carry Diseases

Mongooses can transmit rabies, leptospirosis, and other diseases—posing risks to pets and livestock (although Hawaiʻi is currently rabies-free).

They Outcompete Native Wildlife

As an invasive predator with no natural enemies in Hawaiʻi, mongooses destabilize local ecosystems.

Despite their negative ecological impact, mongooses are fascinating creatures. Here’s a closer look at their behavior and lifestyle:

They Are Extremely Adaptable

Mongooses thrive in forests, fields, urban areas, and even beach parks. Their ability to live almost anywhere has helped them spread quickly.

They Are Opportunistic Predators

Their diet includes:

They Reproduce Quickly

Female mongooses can have two to three litters per year, with up to four pups each time. This rapid reproduction makes population control challenging.

They Are Highly Social

Mongooses often live in family groups, which cooperate to defend territory and raise young.

Because mongooses threaten endangered species, various conservation agencies work to reduce their numbers, especially in sensitive wildlife areas.

Trapping Programs

Live traps are placed in bird nesting zones and coastal regions to protect seabirds.

Predator Fencing

Tall, underground-lined fences block mongooses from entering protected areas where native species nest.

Public Education

Local communities and visitors are encouraged to avoid feeding wildlife, secure trash, and report mongoose sightings in protected zones.

Kauaʻi Prevention Efforts

Kauaʻi remains mongoose-free due to strict monitoring and rapid response programs. Even a single confirmed sighting triggers an immediate investigation.

For most visitors, mongooses pose no direct threat. They rarely interact with humans and generally avoid contact. However, it’s important not to feed or approach them, as doing so encourages unnatural behavior and can harm native wildlife.

If you spot a mongoose during your travels in Hawaiʻi, see it as a reminder of the islands’ unique ecosystem—and the ongoing effort to protect native species.

Mongooses were introduced in the late 1800s to control rats on sugarcane plantations. Unfortunately, the plan failed, and they became a major invasive species.

Mongooses are not typically aggressive toward people. They may carry diseases, so it’s best not to touch or feed them.

They eat bird eggs, insects, small animals, fruits, and sometimes human food scraps—making them a threat to native wildlife.

You can find mongooses on Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, and the Big Island. Kauaʻi has successfully kept them out.

Mongooses raid nests, eat eggs, and prey on chicks—putting already endangered species at even greater risk.

Complete removal is unlikely due to how widespread they are, but targeted population control and predator fencing help protect sensitive areas.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

When most people imagine Hawaiʻi’s wildlife, deer are not the first animals that come to mind. Tropical birds? Yes. Green sea turtles? Absolutely. But deer? Surprisingly, Hawaiʻi is home to one of the most unique deer populations in the Pacific—and their impact on the islands, particularly Maui, has become a major topic of conversation among residents, visitors, conservationists, and hunters alike.

In this blog, we break down how deer arrived in Hawaiʻi, how they’ve adapted to island life, why the population has skyrocketed, and what this means for the future of the islands’ ecosystems. Here’s everything you need to know.

Unlike many species in Hawaiʻi, deer are not native to the islands. The herds seen today—mostly axis deer (also called chital)—were introduced in the 1860s as a gift from the King of India to King Kamehameha V. A few deer were released on Molokaʻi first, and over several decades, populations expanded to Maui, Lanaʻi, and, more recently, the Big Island through illegal transport.

Axis deer were chosen because of their beauty, gentle nature, and potential to support island hunting traditions. At the time, no one realized how quickly they could multiply—or how dramatically they would reshape local landscapes.

Axis deer are naturally suited for warm climates, making Hawaiʻi an ideal environment. They breed year-round, with females capable of giving birth every eight months. With no natural predators, stable weather, and plentiful food sources, populations have grown exponentially.

A few key factors explain their rapid expansion:

1. Ideal Weather Conditions

Hawaiʻi’s mild year-round temperatures support continuous breeding cycles and plentiful food availability.

2. No Natural Predators

On the mainland, deer populations are kept in check by predators like mountain lions and wolves. In Hawaiʻi, nothing naturally keeps their numbers down.

3. Diverse Food Sources

From native shrubs to agricultural crops and residential landscaping, deer have adapted to grazing on a wide variety of vegetation.

Today, Maui alone is estimated to have over 60,000 axis deer, a number that continues to rise.

Deer may be beautiful to see from a distance, but their presence poses major challenges for Hawaiʻi’s fragile ecosystems.

Damage to Native Vegetation

Axis deer eat aggressively, stripping landscapes of native plants and preventing regrowth. This can lead to soil erosion and habitat loss for native species.

Agricultural Losses

Many local farms struggle with deer eating crops like sweet potato, taro, papaya, and even cattle feed. Damage costs millions each year.

Increased Road Hazards

With populations spreading into residential areas, deer-related vehicle accidents have become increasingly common.

Water Resource Strain

Large herds compete with livestock and native wildlife for limited water sources—particularly during droughts.

Communities across Hawaiʻi are working together to manage the deer population in sustainable, humane ways.

Conservation and Eradication Programs

Various state and county-led programs focus on population control, fencing, habitat protection, and targeted management zones.

Regulated Hunting

Hunting is one of the primary tools used to control deer numbers. Many local hunters provide meat for families and communities, reducing waste while helping manage the population.

Road Safety Measures

Fencing, signage, and community awareness campaigns have been implemented in areas with high deer activity.

Local ranchers, conservation groups, and government agencies continue to collaborate on long-term solutions.

While deer are not considered a tourist attraction, visitors may spot them—especially at dawn and dusk.

Some common sighting areas include:

Visitors are encouraged to keep a respectful distance and avoid feeding wildlife.

Axis deer are now firmly established in Hawaiʻi, and their future depends on effective long-term population management. With coordinated efforts, Hawaiʻi aims to balance ecological preservation with cultural, community, and agricultural needs. The deer population will remain part of the islands’ landscape, but sustainable control is essential to protect Hawaiʻi’s native ecosystems for generations to come.

No. Deer are not native to the islands. Axis deer were introduced in the 1860s as a royal gift, and their populations have grown significantly since then.

2. Why are there so many deer in Hawaiʻi?

The climate is ideal, they have no natural predators, and they reproduce year-round—leading to rapid population growth.

3. Where can I see deer in Hawaiʻi?

They are most commonly seen on Maui, Lānaʻi, and Molokaʻi, often in rural or upcountry areas.

4. Are deer harmful to the environment?

Yes. Deer cause major damage to native plants, farms, forests, and water resources, and they contribute to erosion and road hazards.

5. Can you hunt deer in Hawaiʻi?

Yes. Regulated hunting helps manage populations and is an important conservation strategy.

6. Do deer pose a danger to drivers?

Absolutely. Deer often cross roads unexpectedly, especially at night, leading to accidents in rural areas.

7. What type of deer live in Hawaiʻi?

The primary species is the axis deer, known for its spotted coat and graceful build.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

If you've visited the Hawaiian Islands—especially Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, or Maui—there’s a good chance you've seen them strutting across parking lots, crowing at 4 a.m., or boldly wandering through beach parks: wild chickens in Hawaii. These colorful, charismatic birds have become an iconic part of island life, leaving visitors wondering how they got here and why they’re seemingly everywhere.

The story of chickens in Hawaii isn’t just quirky—it’s deeply rooted in history, ecology, culture, and even natural disasters.

The first chickens in Hawaii didn’t arrive by accident—they were brought here over 1,000 years ago by the original Polynesian settlers. These early voyagers carried red junglefowl, known locally as moa, for food, eggs, feathers, and cultural practices.

These ancient birds were smaller, more vibrant, and more agile than the modern domesticated chicken. In many areas—especially Kauaʻi—today’s wild chickens are believed to be a genetic blend of these ancient junglefowl and escaped domestic chickens.

This mix explains why Hawaii’s chickens are often:

While chickens have existed in Hawaii for centuries, their dramatic population boom is far more recent.

Two major storms played a huge role:

Hurricane Iwa (1982)

Hurricane Iniki (1992)

These back-to-back hurricanes devastated parts of Kauaʻi and Oʻahu, destroying thousands of chicken coops. Domesticated birds escaped into the wild, interbred with ancient junglefowl, and reproduced rapidly in the tropical climate.

Without many natural predators—and with consistent warm weather—the chicken populations exploded and never went back down.

Chickens thrive in Hawaii for several reasons:

🌴 Warm, tropical climate

No harsh winters mean year-round breeding and foraging.

🪵 Abundant food sources

Chickens feast on:

🐈 Few natural predators

On some islands—especially Kauaʻi—there are no mongoose, which means chickens can roam freely without the threat of this common predator found elsewhere in Hawaii.

With no competition and plenty of resources, the birds reproduce quickly and consistently.

While not technically native, chickens in Hawaii have become a memorable cultural symbol. Many locals view them as harmless, humorous, and even lucky. Their frequent crowing has become part of the daily soundtrack of island life.

In Hawaiian culture:

Though today’s chickens are often seen running through parking lots or dancing around picnic tables, they remain part of Hawaii’s living cultural landscape.

Many visitors are surprised to learn that on some islands—especially Kauaʻi—wild chickens are protected under state law because they are considered descendants of ancient junglefowl.

This means:

However, rules vary island-to-island, and the state continues to explore humane management solutions in areas where overpopulation becomes a challenge.

The chickens in Hawaii have adapted well to human presence. Over time, they’ve learned that:

Their boldness is simply a learned behavior from decades of coexisting with humans.

While charming, the vast number of chickens can cause issues:

Some local governments attempt population control, but due to the birds’ protected status and rapid breeding, long-term solutions are complex.

The abundance of chickens in Hawaii is the result of ancient Polynesian migration, powerful hurricanes, ideal island conditions, and cultural coexistence. Whether you find them adorable or noisy, these wild birds have firmly rooted themselves into Hawaii’s identity—strutting across the islands as feathered ambassadors of history, resilience, and tropical charm.

Why are there so many chickens in Hawaii?

Because ancient Polynesians brought junglefowl to the islands, and later hurricanes released domestic chickens into the wild. With warm weather and few predators, the population multiplied rapidly.

Are the chickens in Hawaii native?

Not exactly—but many are descendants of the ancient moa brought by Polynesians, mixed with modern domestic chickens.

Why are there more chickens on Kauaʻi than other islands?

Kauaʻi doesn’t have mongoose, a major chicken predator found on most other Hawaiian islands, allowing populations to flourish.

Are wild chickens protected in Hawaii?

Some populations—especially on Kauaʻi—are protected because of their genetic ties to ancient junglefowl.

Do wild chickens bother tourists?

Some visitors enjoy them, while others find them noisy. They may approach picnics or outdoor dining areas, but they are generally harmless.

Can you feed chickens in Hawaii?

Feeding them is discouraged because it increases dependency on humans and can contribute to overpopulation.

Where are you most likely to see wild chickens?

Beaches, parks, parking lots, hiking trails, and roadside areas across Kauaʻi, Maui, and Oʻahu.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

In Hawaiʻi, few words carry as much depth and warmth as ʻohana (pronounced oh-HAH-nah). At first, it might seem like a simple translation of “family,” but within Hawaiian culture, ʻohana represents far more. It’s a way of life — a bond that extends beyond bloodlines, encompassing community, land, and shared responsibility.

The word ʻohana comes from ʻoha, the shoot or offshoot of the kalo (taro) plant, and the suffix -na. In Hawaiian tradition, kalo is sacred — it’s considered the ancestor of the Hawaiian people. According to legend, the first child of the gods became the kalo plant, while the second became the first human being. This story symbolizes that all people are connected through the same root system, much like the shoots of a single taro plant.

This understanding of shared roots shapes how Hawaiians view family and community. Just as each taro shoot depends on the same root for nourishment, people rely on one another for strength, identity, and survival. ʻOhana is not just who you live with — it’s everyone who grows from the same foundation of love, respect, and connection.

In Western culture, “family” often refers to the nuclear unit — parents and children. In Hawaiian life, ʻohana is much broader. It includes extended family, close friends, and even those who are embraced through love or care, not just ancestry.

Many Hawaiian families live in multi-generational homes, where grandparents, parents, and children share the same space. These living arrangements create strong bonds, where elders pass down wisdom and traditions, and younger generations learn to care for both people and land.

ʻOhana also extends to hānai relationships, where someone is taken in or raised by another family. This type of adoption — formal or informal — is a long-standing part of Hawaiian culture. Through hānai, the circle of ʻohana continues to expand, reminding everyone that family is not defined by blood, but by the love and responsibility we choose to share.

In modern Hawaiʻi, this sense of belonging goes beyond the household. Neighbors, friends, and even visitors can become part of an ʻohana when they are treated with respect and kindness. It’s a reminder that everyone has a place — and that everyone matters.

ʻOhana is more than a concept — it’s something to live every day. To be part of an ʻohana means to look out for one another, support each other through challenges, and celebrate together in times of joy.

At its core, ʻohana carries several values deeply woven into Hawaiian life:

This mindset is why the saying “ʻOhana means family, and family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten” resonates so deeply. It’s not just a phrase — it’s a promise.

Even in modern times, ʻohana remains the heartbeat of Hawaiian culture. In times of hardship, families and communities come together, providing food, shelter, and support to those in need. You can see it in how communities rally during natural disasters, or how neighborhoods unite to care for elders and children.

The influence of ʻohana even appears in everyday life — from housing to hospitality. Many homes have “ʻohana units,” small dwellings designed for extended family members to live close by. This reflects the value of staying connected across generations.

In tourism and local life alike, visitors often hear locals say, “Welcome — you’re part of our ʻohana now.” It’s more than a greeting; it’s an invitation into a circle of care, respect, and belonging that defines what it means to live with aloha.

ʻOhana isn’t limited to the islands — it’s a perspective anyone can embrace. You can live with the spirit of ʻohana by treating others with compassion, lending a helping hand, and respecting the world around you.

Here are a few simple ways to carry the ʻohana spirit into your daily life:

When you live with this mindset, you help nurture communities that thrive on kindness and unity — much like the Hawaiian islands themselves.

ʻOhana is one of Hawaiʻi’s greatest gifts to the world — a reminder that we are all connected. It’s about recognizing that family is not only who we are born to, but also who we grow with, love, and support. It’s about caring for each other and the planet we share.

So the next time someone calls you part of their ʻohana, take it to heart. It means you belong — to a network of love, loyalty, and life that stretches far beyond the horizon.

1. What is the deeper meaning of ʻohana in Hawaiʻi?

ʻOhana goes beyond the Western idea of “family.” It represents a way of life rooted in love, respect, and shared responsibility. ʻOhana includes not just blood relatives but friends, neighbors, and community members who care for one another like family.

2. Where does the word ʻohana come from?

The term ʻohana originates from ʻoha, meaning the offshoot of the kalo (taro) plant, combined with the suffix -na. In Hawaiian tradition, the kalo plant symbolizes humanity’s shared roots — a reminder that all people are connected like shoots from the same taro root.

3. How does ʻohana differ from the Western idea of family?

While Western families are often nuclear, Hawaiian ʻohana includes extended relatives, close friends, and even those brought in through love and care rather than blood. This inclusivity is seen in practices like hānai adoption, where families take in others as their own.

4. What values define the spirit of ʻohana?

ʻOhana embodies core Hawaiian values such as mutual care, respect for elders (kupuna), stewardship of the land (ʻāina), and inclusion. Living with the ʻohana spirit means ensuring no one is left behind — emotionally, spiritually, or physically.

5. How does ʻohana show up in modern Hawaiian life?

ʻOhana remains central to life in Hawaiʻi today. Families often live in multi-generational homes or ʻohana units that keep loved ones close. Communities unite in times of hardship, and even visitors are often welcomed as part of the ʻohana, reflecting the islands’ deep sense of hospitality and aloha.

6. Can people outside Hawaiʻi live with the ʻohana spirit?

Absolutely. ʻOhana is a universal value that can be practiced anywhere. You can live with ʻohana by treating others with kindness, giving generously, staying connected with loved ones, and respecting the environment — the same land and life that sustain us all.

7. What is the lasting message of ʻohana?

ʻOhana reminds us that we are all part of one family — connected by love, responsibility, and the shared rhythm of life. It’s a call to care for one another and the world around us, ensuring that no one is left behind or forgotten.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

There are few places on Earth where sunrise feels as sacred, surreal, and powerful as it does atop Haleakalā, the “House of the Sun.” Towering 10,023 feet above sea level, this dormant volcano dominates the eastern half of Maui and offers one of the most breathtaking sunrise experiences in the world. For many travelers, watching the Sunrise on Haleakalā’s is not just a highlight of their trip—it’s a spiritual moment, a connection to the island’s natural beauty and deep Hawaiian heritage.

In Hawaiian, Haleakalā translates to “House of the Sun.” According to Hawaiian legend, the demigod Māui climbed to the summit of this great volcano to capture the sun. The story tells that the sun moved too quickly across the sky, making the days too short. To help his mother, who needed more daylight to dry her kapa (cloth made from bark), Māui lassoed the sun’s rays and made it promise to slow its journey across the sky. The legend gives Haleakalā its name and its enduring connection to the rising sun.

When you stand at the summit as the first golden light spills over the horizon, it’s easy to feel the power of this ancient tale. The moment feels suspended between myth and reality—a perfect balance of cultural reverence and natural wonder.

Reaching Haleakalā’s summit requires a bit of planning and preparation, but the effort is well worth it. The entrance to Haleakalā National Park is about a 1.5- to 2-hour drive from most resort areas in West or South Maui, depending on traffic and weather. Most visitors begin their journey in the early hours—around 2:30 or 3:00 a.m.—to arrive at the summit in time for sunrise, which generally occurs between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m. depending on the season.

The drive itself is part of the adventure. Winding mountain roads climb steadily upward through eucalyptus forests and pastures, eventually emerging into a lunar-like landscape as you approach the upper slopes. Temperatures drop dramatically as you ascend—sometimes dipping below freezing before dawn—so warm clothing, jackets, and blankets are essential.

Because of the popularity of this iconic experience, the National Park Service requires a sunrise reservation for visitors entering the summit area between 3:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. Reservations are available online through the Haleakalā National Park website and often sell out weeks in advance. The $1.50 per vehicle reservation fee is in addition to the regular park entrance fee, which can be paid upon arrival or with a national park pass.

If you aren’t able to secure a reservation, you can still visit later in the day for daytime hiking or return for the Haleakalā sunset, which offers equally stunning views and doesn’t require a special permit.

Standing above the clouds at more than 10,000 feet, visitors often find themselves surrounded by an ocean of mist as stars sparkle overhead. As the horizon begins to lighten, a deep hush falls over the crowd. Then, slowly, the first rays of sunlight pierce the horizon, casting fiery hues of gold, pink, and orange across the crater and the clouds below.

In that moment, everything feels still—only the sound of the wind and the soft murmur of awe from fellow travelers. The sight is often described as transcendent, evoking a sense of gratitude and connection to something greater than oneself.

It’s no wonder that Native Hawaiians have long regarded Haleakalā as a sacred place. For centuries, it has been a site for ceremony, reflection, and renewal.

Because conditions at the summit are unique, proper preparation can make the experience far more enjoyable:

After sunrise, many visitors choose to explore the park’s incredible landscapes. The Sliding Sands Trail (Keonehe‘ehe‘e Trail) descends into the crater, offering surreal views of red cinder cones, lava flows, and native plants like the rare ʻāhinahina (silversword). The contrast between the barren volcanic terrain and the lush valleys below showcases the island’s remarkable ecological diversity.

Another option is to drive down to the Kīpahulu District, located near Hāna on Maui’s east side. This coastal section of the park features waterfalls, pools, and rainforests—a lush counterpart to the stark summit above.

Witnessing the sunrise from Haleakalā is more than a sightseeing event—it’s an emotional and almost spiritual journey. The mountain’s immense silence, the crisp air, and the slow birth of daylight all combine to create a once-in-a-lifetime memory.

Whether you come for photography, adventure, or quiet reflection, the experience connects you to the heart of Maui—to the spirit of Aloha ʻĀina, the love and respect for the land.

1. Why is sunrise on Haleakalā considered such a special experience?

Sunrise on Haleakalā is often described as sacred and surreal because you’re standing above the clouds at over 10,000 feet, watching the first light spill across a massive volcanic crater. The colors, stillness, and scale of the moment feel almost spiritual. For many visitors, it becomes the highlight of their Maui trip, offering a rare connection to Hawaiian culture and natural beauty.

2. What does the name Haleakalā mean, and why is it important in Hawaiian culture?

“Haleakalā” translates to “House of the Sun.” According to Hawaiian legend, the demigod Māui climbed the mountain to lasso the sun, slowing its journey across the sky so his mother would have more daylight. This story ties the summit directly to the rising sun, giving the sunrise experience deep cultural significance. When you watch the dawn unfold, it's easy to feel the power of this legend.

3. How do I get to the summit of Haleakalā for sunrise?

Reaching the summit requires a 1.5–2 hour drive from most resort areas. Because sunrise happens between 5:30–6:30 a.m., most people leave their hotel around 2:30–3:00 a.m. The drive is part of the adventure—winding roads, steep climbs, and dramatic temperature drops as you ascend into a lunar-like landscape. Warm clothing is essential, as temperatures often dip below freezing before dawn.

4. Do I need a reservation to watch the sunrise on Haleakalā?

Yes. The National Park Service requires a sunrise reservation for any vehicle entering the summit from 3:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. Reservations must be made in advance online and often sell out weeks ahead. The cost is $1.50 per vehicle, separate from the standard park entrance fee. If you don’t get a sunrise reservation, you can still enjoy daytime visits or return for sunset—no permit required.

5. What is sunrise on Haleakalā actually like?

It begins in complete darkness under a star-filled sky. As the horizon brightens, the clouds below look like an ocean of mist. Then the sun rises, casting fiery shades of gold, orange, and pink across the crater. The moment is silent, powerful, and emotional—many describe it as a once-in-a-lifetime experience that feels bigger than a typical sightseeing activity.

6. How cold does it get at the summit, and what should I wear?

It can be very cold—temperatures often drop into the 30s or even below freezing before sunrise. Strong winds can make it feel even colder. Bring:

7. What should I bring with me for the Haleakalā sunrise?

Along with warm clothing, bring:

8. Is the sunrise worth it if I can’t get a reservation?

Yes—because sunset at Haleakalā is just as stunning and does not require a special permit. You’ll still enjoy breathtaking colors across the crater, and the crowds are typically smaller. You can also explore the summit area during the day, hike trails, or return at night for stargazing.

9. What can I do in Haleakalā National Park after sunrise?

Many visitors choose to explore:

10. How difficult is the drive back down after sunrise?

The descent can be steep with sharp turns, but it’s manageable if you drive slowly and stay alert. After sunrise, visibility improves, making it easier than the early-morning climb. Just be sure to pull over safely for photos instead of stopping in the road.

11. Why do locals consider Haleakalā a sacred place?

For Native Hawaiians, Haleakalā is tied to cultural stories, ceremonies, and deep spiritual meaning. The summit is a place for reflection, renewal, and honoring the land. Visitors are encouraged to move respectfully—keeping noise low, staying on trails, and leaving no trace.

12. Is sunrise on Haleakalā worth waking up at 2:30 a.m. for?

Almost everyone who experiences it says yes. The combination of natural beauty, cultural meaning, and the feeling of standing above the clouds makes it unforgettable. Whether you’re a photographer, nature lover, or spiritual seeker, the sunrise often becomes one of the most meaningful moments of the entire Maui trip.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

On the western shores of Maui, nestled against the world-famous Kaʻanapali Beach, lies Black Rock Beach, one of the island’s most unique coastal gems. Known locally as Puʻu Kekaʻa, this dramatic lava point is more than just a picturesque spot—it’s a place where Hawaiian culture, natural beauty, and outdoor adventure come together. For travelers seeking both relaxation and excitement, Black Rock Beach offers an unforgettable experience that combines history, snorkeling, cliff diving, and breathtaking sunsets.

Black Rock Beach is located at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach, one of Maui’s most visited and celebrated shorelines. Stretching for about three miles, Kaʻanapali Beach is known for its soft golden sand, turquoise waters, and views that sweep across the Pailolo Channel toward Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi. At its northernmost point, the volcanic lava formation known as Black Rock juts dramatically into the ocean, creating a striking contrast against the sandy expanse of the beach.

This natural barrier not only adds beauty to the landscape but also shapes the underwater environment. The lava rock formation provides shelter for an abundance of marine life, making the area around Black Rock one of the best snorkeling destinations on Maui.

Beyond its scenic appeal, Black Rock holds deep cultural importance in Hawaiian tradition. According to Hawaiian legends, Puʻu Kekaʻa is believed to be a leina, or a jumping-off point, where spirits would leap into the afterlife to join their ancestors. Because of this sacred history, the site remains a revered place that blends spirituality with natural wonder.

To honor this heritage, the Sheraton Maui Resort, located adjacent to Black Rock, continues a long-standing tradition of a nightly cliff diving ceremony. At sunset, a torchbearer lights the tiki torches along the cliff, climbs to the top, and dives gracefully into the ocean—symbolizing the legendary feats of Maui’s ancient chiefs. This ceremony connects visitors to the island’s rich cultural past while offering a breathtaking spectacle.

One of the biggest draws of Black Rock Beach is snorkeling. The waters around the lava point are teeming with tropical fish, sea turtles (honu), and vibrant coral. Beginners and experienced snorkelers alike will find plenty to enjoy, as the area is accessible directly from the shore and offers relatively calm conditions, especially in the mornings.

Some of the marine life commonly spotted here includes:

Because Black Rock provides a natural barrier, visibility is often excellent, making it ideal for underwater photography and close encounters with Maui’s marine biodiversity.

For those seeking adrenaline, cliff diving off Black Rock has become one of the most iconic activities in Kaʻanapali. While the jump itself is about 20 to 30 feet, the thrill of leaping into the clear waters below against the backdrop of a Hawaiian sunset is unforgettable. Many visitors gather in the evening to watch brave locals and visitors alike take the plunge.

It’s worth noting that safety should always come first—conditions can change quickly, and the ocean demands respect. Anyone considering a dive should ensure calm waters and proper physical ability before attempting it.

Black Rock Beach is also one of the best spots on Maui to watch the sunset. As the sun sinks into the Pacific, the cliffs and ocean reflect brilliant shades of orange, pink, and purple. From the vantage point of Black Rock, you may also catch a glimpse of the neighboring islands silhouetted against the evening sky. During the winter months, it’s not uncommon to see humpback whales breaching offshore, adding even more magic to the scene.

Black Rock Beach is easily accessible, located at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach and near many resorts, shops, and restaurants. Public beach access and parking are available, though spots can fill quickly during peak times. Visitors should plan ahead and consider arriving early to secure parking and enjoy the calmer morning waters for snorkeling.

Because Black Rock Beach is connected to the resort area, amenities such as restrooms, dining options, and rentals for snorkeling gear are nearby. This makes it a convenient destination for families, couples, and solo travelers alike.

Black Rock Beach in Kaʻanapali, Maui, offers much more than a stunning shoreline. It’s a place where Hawaiian culture is alive, where adventure meets tranquility, and where visitors can experience the best of Maui’s natural beauty. Whether you come for snorkeling, cliff diving, or simply to soak in a legendary sunset, Black Rock Beach promises an experience you’ll never forget.

1. What makes Black Rock Beach in Maui so special?

Black Rock Beach—also known as Puʻu Kekaʻa—is unique because it blends stunning natural beauty, rich Hawaiian cultural history, incredible snorkeling, and cliff diving into one unforgettable experience. Located on the northern end of famed Kaʻanapali Beach, it’s a place where adventure, relaxation, and tradition meet. Visitors can explore marine life, enjoy sunsets, and take in one of Maui’s most iconic oceanfront ceremonies.

2. Where exactly is Black Rock Beach located?

Black Rock Beach sits at the northern end of Kaʻanapali Beach, one of Maui’s best-known shorelines. The dramatic lava formation juts into the Pacific Ocean, creating a natural point that divides the beach and also protects the reef below. It’s easily accessible from Kaʻanapali’s resorts, boardwalk, and public beach access areas.

3. What is the natural setting like at Black Rock Beach?

Black Rock Beach is famous for its golden sand, turquoise waters, and striking black lava point. The views extend across the Pailolo Channel toward the islands of Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi. The lava rock formation not only creates a beautiful backdrop but also helps shelter marine life, making the waters especially clear and rich with sea creatures.

4. What is the cultural significance of Black Rock (Puʻu Kekaʻa)?

In Hawaiian tradition, Puʻu Kekaʻa is believed to be a leina, or spiritual “jumping-off point,” where souls would leap into the afterlife. This makes it a sacred and deeply respected place. To honor this heritage, the Sheraton Maui continues the historic nightly cliff diving ceremony, featuring torches, storytelling, and a symbolic dive at sunset. This ceremony reflects the feats of ancient Hawaiian chiefs and connects visitors to the island’s cultural past.

5. Is Black Rock Beach a good place for snorkeling?

Yes—Black Rock is one of Maui’s top snorkeling spots. The lava formation provides shelter for many species of marine life, and visibility is often excellent, especially in the mornings. Snorkelers commonly see tropical fish like butterflyfish, parrotfish, and Moorish idols, as well as Hawaiian green sea turtles (honu). The area is easy to access directly from the shore, making it great for both beginners and experienced snorkelers.

6. Can you go cliff diving at Black Rock?

Cliff diving is one of the most iconic activities at Black Rock. The jump is usually 20–30 feet depending on tide levels. Many visitors try it, especially during calm ocean conditions. However, safety should always come first—check the water conditions, avoid rough surf, and only jump if you’re confident and capable. Many people prefer to watch the brave divers rather than jump themselves.

7. What is the sunset like at Black Rock Beach?

Black Rock is one of Maui’s best sunset spots. As the sun dips into the ocean, the sky glows with shades of pink, orange, and purple. The silhouette of Molokaʻi and Lānaʻi adds to the beauty, and during winter months, you may even see humpback whales breaching offshore. The nightly cliff diving ceremony at sunset also makes the moment even more memorable.

8. Is Black Rock Beach easy to access, and are there facilities nearby?

Yes. Black Rock Beach is located right next to major Kaʻanapali resorts, so amenities like restrooms, dining options, and snorkel rentals are close by. Public beach access and limited parking are available, but parking fills up quickly—arriving early is recommended. The boardwalk makes it easy to walk from nearby hotels and shops.

9. When is the best time to visit Black Rock Beach for snorkeling or swimming?

Morning is typically the safest and calmest time for ocean activities. Winds and surf conditions tend to increase later in the day. Arriving early also helps with parking and ensures clearer visibility underwater. Always check the current ocean conditions, as the waters around Black Rock can change quickly.

10. Are there safety tips I should know before snorkeling or cliff diving at Black Rock?

Yes—ocean safety is essential:

11. What else can you do near Black Rock Beach?

Visitors can enjoy walking the Kaʻanapali Beach boardwalk, book snorkeling or whale-watching tours, dine at nearby restaurants, or relax on the wide expanse of Kaʻanapali Beach. The area is lively, walkable, and full of both cultural and adventure opportunities, making it perfect for families, couples, and solo travelers.

12. Why is Black Rock Beach considered a must-visit spot on Maui?

Black Rock Beach stands out because it blends natural beauty, Hawaiian culture, ocean adventure, and iconic sunsets in one unforgettable location. Whether you're snorkeling with turtles, watching a traditional cliff diving ceremony, or simply soaking in the view, it offers an authentic Maui experience you won’t find anywhere else.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

For many adventure seekers, nothing quite compares to the rush of gliding high above treetops, rivers, and mountains on a zipline. The activity, once primarily used as a means of transport in remote regions, has now become a worldwide attraction for those craving adrenaline, scenic beauty, and unique outdoor experiences. Today, ziplines are no longer just about speed and height—they’re about immersing yourself in nature, conquering fears, and creating lasting memories.

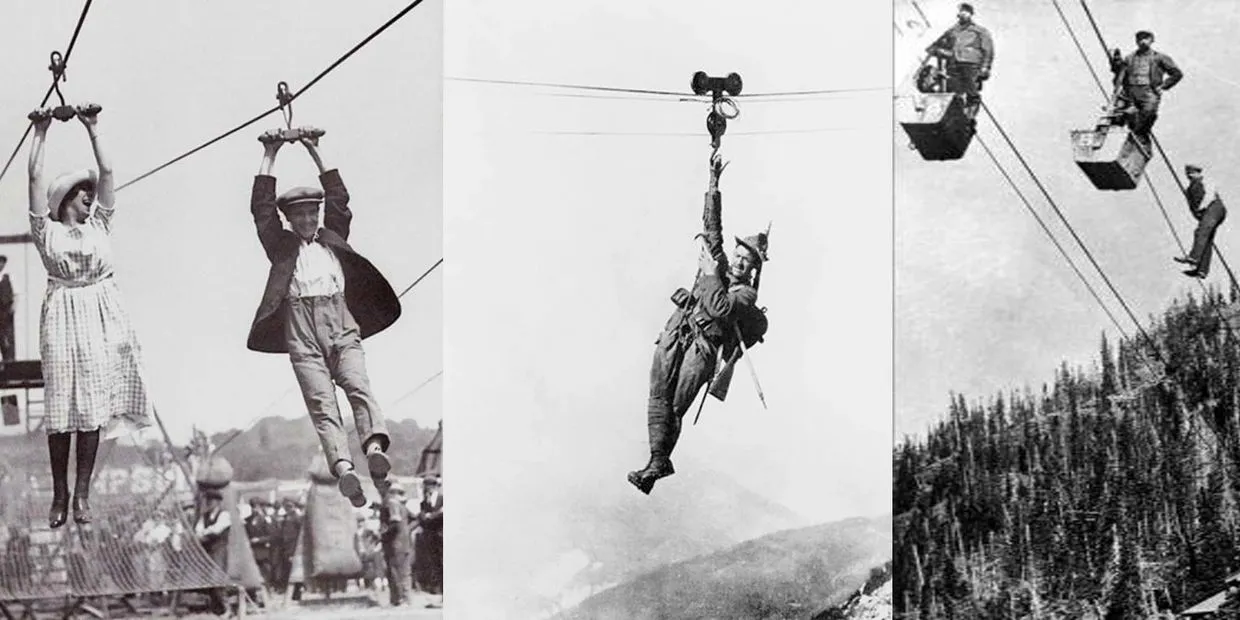

Though ziplining may seem like a modern adventure activity, its origins go back centuries. Villagers in remote areas of the Himalayas, China, and South America used early versions of ziplines as a practical way to transport goods, supplies, and even people across rivers and valleys where bridges were unavailable.

In Costa Rica during the 1970s, biologists popularized the concept of ziplines as a way to study rainforests without disturbing the fragile ecosystem. It wasn’t long before tourism companies recognized the thrill and beauty of this experience, transforming ziplining into the recreational activity we know today.

The core attraction of a zipline is simple: the exhilarating sensation of soaring through the air. Riders are strapped into a secure harness, clipped to a sturdy cable, and propelled by gravity as they glide from one platform to another. The speed, height, and exposure to open air create an adrenaline rush unlike any other.

Ziplines are often located in some of the most beautiful natural landscapes around the world. From tropical rainforests and mountain ridges to coastal cliffs and canyons, zipline tours allow riders to experience scenery from a bird’s-eye perspective. What might take hours to hike can be appreciated in moments while flying through the sky.

Unlike many extreme sports, a zipline does not require years of training or advanced fitness levels. Most tours are accessible to beginners, and professional guides provide safety briefings to ensure comfort and confidence. This makes ziplines a family-friendly adventure that appeals to kids, adults, and even seniors looking to step outside their comfort zones.

Corporate groups and schools often book zipline excursions as team-building activities. Facing a challenge together encourages trust, cooperation, and bonding. On a personal level, completing a ride helps individuals build confidence and overcome fears, particularly if they are afraid of heights.

One of the most common questions people ask before riding a zipline is whether it’s safe. The good news is that modern ziplines are built with strict safety standards and equipment designed to handle high tension and weight loads. Harnesses, helmets, and dual-line systems are common features. Operators are trained to inspect cables and platforms regularly, ensuring every ride meets professional safety requirements.

Before each ride, participants typically receive a briefing on proper techniques—how to hold the straps, where to keep their hands, and how to brake if necessary. Safety is always the top priority, allowing riders to focus on enjoying the adventure.

Not all ziplines are the same, and the variations add to the excitement:

If you’re planning your first zipline adventure, here are a few tips to make the most of it:

At its heart, ziplining is about more than the thrill of speed. It’s a way to connect with nature, to conquer personal challenges, and to share a unique experience with friends and family. The blend of excitement, safety, and accessibility has made ziplines one of the fastest-growing outdoor adventure activities worldwide.

Whether you’re gliding over a rainforest in Costa Rica, soaring above valleys in Hawaii, or trying an urban zipline in the city, the experience will leave you with a new perspective—both literally and figuratively.

1. What exactly is ziplining, and why do people love it so much?

Ziplining is an adventure activity where you glide through the air on a secure cable, usually while harnessed in. People love it because it combines adrenaline, incredible scenery, and the thrill of flying. It’s one of the few outdoor adventures that allows beginners to instantly experience the sensation of soaring over treetops, valleys, rivers, and mountains.

2. Where did ziplining come from originally?

Ziplining actually has ancient roots. Early versions were used in places like the Himalayas, China, and South America as a practical way to transport goods or people across rivers and deep valleys. In the 1970s, biologists in Costa Rica began using ziplines to study rainforests from above. That idea evolved into the recreational zipline tours we know today.

3. Why is ziplining such a popular adventure activity now?

People are drawn to ziplining because it offers:

4. Do I need to be super fit or experienced to ride a zipline?

No! Most ziplines are designed for beginners and families, and guides provide all safety instructions you need. As long as you meet the weight requirements and can climb a few stairs or platforms, you can enjoy the experience. Kids, adults, and even seniors can participate safely.

5. Is ziplining safe? How do operators ensure rider safety?

Ziplining is very safe when operated correctly. Modern ziplines follow strict engineering and safety standards. Safety measures typically include:

6. What types of ziplines are there around the world?

There are several kinds of zipline experiences, each offering its own thrill:

7. What are some of the most famous zipline destinations in the world?

Top zipline hotspots include:

8. What should I wear when ziplining for the first time?

Wear clothes you can move in—activewear is best. Avoid skirts, dresses, or loose accessories that can get tangled. Closed-toe shoes (like sneakers or hiking shoes) are essential for safe takeoffs and landings. Tie back long hair and leave dangling jewelry at home.

9. What should I expect during the safety briefing before a zipline tour?

Guides will walk you through:

10. Is ziplining a good activity for families or group outings?

Definitely. Ziplining is one of the best family-friendly adventures because it blends teamwork, encouragement, and shared excitement. Many corporate groups and school programs use ziplining as a team-building activity because it promotes trust and confidence.

11. How scary is ziplining if I’m afraid of heights?

It’s normal to feel nervous at first, but most people find that once they take off, the fear fades into excitement. Ziplining can actually help people overcome height-related fears because you're securely harnessed and supported the entire time. Guides are trained to help you feel safe and comfortable.

12. Why do people say ziplining is more than just a ride?

Ziplining offers a deeper experience beyond the thrill:

13. What tips should first-time zipliners know before going?

Here’s what helps most beginners:

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

When people think of Hawai‘i, they often picture swaying palm trees, turquoise waters, and fragrant flowers. But nestled among the islands’ unique natural wonders is a remarkable bird that holds deep cultural and ecological significance—the Nēnē, or Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis). As Hawai‘i’s official state bird, the Nēnē symbolizes resilience, adaptation, and the importance of conservation in preserving the islands’ natural heritage.

The Nēnē is endemic to Hawai‘i, meaning it is found nowhere else on Earth. Believed to have evolved from the Canada goose thousands of years ago, these birds adapted to the islands’ volcanic landscapes, grasslands, and shrublands. Over time, they developed distinct features that set them apart from their ancestors.

One of the most fascinating adaptations is their feet. Unlike most geese, the Nēnē has partially webbed feet, which allow it to walk on rugged lava rock, climb slopes, and navigate dry grasslands. This adaptation reflects their transition from a primarily aquatic environment to a more terrestrial lifestyle in Hawai‘i’s unique terrain.

The Nēnē is a medium-sized goose, about 25 inches long with a wingspan of roughly three feet. It is easily recognized by its black face and crown, buff-colored cheeks, and strong barred patterns across its neck, which look almost like a necklace of grooves. The plumage blends beautifully into the volcanic landscapes of the islands, offering them natural camouflage.

Unlike other geese that are known for their loud honking, the Nēnē has a softer, more melodic call. These birds are primarily herbivores, feeding on native shrubs, grasses, and berries, particularly the fruit of the ‘ōhelo berry plant, which also holds significance in Hawaiian culture.

Nēnē are monogamous, and pairs often form strong, lifelong bonds. During the nesting season, which usually spans from October to March, females lay three to five eggs in ground nests hidden among vegetation. The goslings are able to walk and feed themselves within days of hatching, though they remain under the care and protection of their parents.

Despite its symbolic and ecological importance, the Nēnē came dangerously close to extinction in the 20th century. By the 1950s, fewer than 30 birds remained in the wild. Habitat destruction, hunting, and the introduction of predators such as mongoose, rats, and feral cats had decimated populations across the islands.

Recognizing the crisis, conservationists launched ambitious recovery programs. Captive breeding efforts, spearheaded in part by conservationists in Hawai‘i and abroad, played a pivotal role in saving the Nēnē. Birds raised in captivity were carefully reintroduced into protected areas across the islands, including national parks, wildlife refuges, and conservation lands.

Today, the Nēnē population has rebounded to over 3,000 individuals, with stable populations on Hawai‘i Island, Maui, Kaua‘i, and even reintroduction efforts on O‘ahu. While the bird is still listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, its recovery is often celebrated as one of the greatest conservation success stories in Hawai‘i.

For Native Hawaiians, the Nēnē has long held a place of cultural reverence. It is seen not only as a symbol of the islands but also as a living connection to the land (‘āina). Some traditions suggest the bird embodies qualities of endurance and adaptability—traits mirrored in the Hawaiian people themselves.

The bird’s name, “Nēnē,” is said to reflect its soft, gentle call. In Hawaiian culture, the naming of animals often connects to their spirit and behavior, highlighting a deep respect for the natural world.

When the Nēnē was officially designated the state bird of Hawai‘i in 1957, it became a powerful emblem of pride and identity. Its survival story is now tied not only to conservation biology but also to cultural renewal and education, reminding residents and visitors alike of the need to protect Hawai‘i’s fragile ecosystems.

If you’re visiting Hawai‘i and would like to see the Nēnē in its natural habitat, you’re in luck. National parks and reserves offer safe havens where these birds thrive. Some of the best places to encounter them include:

When observing these birds, it’s important to keep a respectful distance. Feeding Nēnē is strictly prohibited, as it can disrupt their natural diet and behavior. Responsible wildlife viewing ensures their continued survival and helps protect the delicate balance of Hawai‘i’s ecosystems.

The Nēnē’s story is more than just a tale of a bird brought back from the brink of extinction. It is a reminder of the interconnectedness of culture, conservation, and community. By saving the Nēnē, Hawai‘i has also safeguarded the integrity of its landscapes and preserved a vital link between people and place.

As Hawai‘i continues to face environmental challenges such as climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species, the survival of the Nēnē serves as both a beacon of hope and a call to action. Protecting this bird means protecting Hawai‘i itself.

1. What is the Nēnē, and why is it considered Hawaii’s state bird?

The Nēnē, or Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis), is the official state bird of Hawai‘i. It’s beloved for its cultural importance, resilience, and unique adaptations to the islands. Found nowhere else in the world, the Nēnē symbolizes Hawaii’s commitment to protecting its native wildlife and preserving its natural heritage.

2. Is the Nēnē found anywhere outside of Hawaii?

No. The Nēnē is endemic to Hawai‘i, meaning it exists only in the Hawaiian Islands. It evolved from the Canada goose thousands of years ago and adapted to Hawaii’s volcanic landscapes, grasslands, and shrublands. Its story is a powerful reminder of how isolated island ecosystems create one-of-a-kind species.

3. What makes the Nēnē different from other geese?

The Nēnē has several unique characteristics:

4. What does the Nēnē look like and how does it behave?

Nēnē are medium-sized geese with black heads, buff-colored cheeks, and distinctive striped neck feathers. They blend seamlessly into volcanic landscapes. They’re also:

5. How close did the Nēnē come to extinction?

In the 1950s, the Nēnē population dropped to fewer than 30 birds, putting the species on the brink of extinction. Habitat loss, hunting, and invasive predators such as mongoose and feral cats nearly wiped them out.

Thanks to dedicated captive breeding programs and reintroduction efforts, population numbers now exceed 3,000 birds—one of Hawaii’s greatest conservation success stories.

6. Why is the Nēnē important in Hawaiian culture?

The Nēnē holds deep cultural significance for Native Hawaiians. Its name comes from its gentle vocalizations, and the bird is often associated with adaptability, endurance, and a strong connection to the ʻāina (land). When Hawai‘i designated the Nēnē as its state bird in 1957, it became a symbol of pride, identity, and the importance of caring for the land and its wildlife.

7. Where can I see the Nēnē in Hawaii today?

If you’re visiting Hawai‘i, you can spot Nēnē in several protected natural areas:

8. Why is it important not to feed Nēnē?

Feeding Nēnē may seem kind, but it harms them. Human food disrupts their natural diet, increases dependency, and can cause dangerous behavior near roads or humans. Feeding wildlife also violates federal and state regulations. The best way to help Nēnē is by viewing them responsibly and supporting conservation efforts.

9. How did conservationists help save the Nēnē?

Conservationists used a combination of:

10. Why does the Nēnē matter to Hawaii’s ecosystem?

As a native herbivore, the Nēnē plays a role in seed dispersal, vegetation control, and maintaining healthy grassland ecosystems. Its survival supports the overall balance of Hawaii’s fragile natural environment. Saving the Nēnē also helps preserve countless native plant species and habitats that depend on responsible stewardship.

11. What does the recovery of the Nēnē teach us about conservation?

The Nēnē’s comeback shows that community support, scientific research, and cultural awareness can make a real difference in restoring endangered species. It also highlights the importance of protecting Hawaii’s ecosystems from modern threats like invasive species and climate change.

12. Is the Nēnē friendly or safe to approach?

Nēnē are gentle birds but should never be approached or touched. They are protected by law, and human interaction can stress them or disrupt their behavior. Observe from a respectful distance, use your camera’s zoom, and allow them to go about their natural activities undisturbed.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Sitting in the heart of the lush Iao Valley, on the island of Maui, stands one of Hawaii’s most iconic natural landmarks: the Iao Needle. Rising 1,200 feet from the valley floor, this green-mantled pinnacle is more than just a geological marvel—it is a place of history, legend, and cultural significance. Visitors from around the world journey to this serene valley to marvel at its beauty, hike its trails, and connect with the stories of old Hawaii that echo through the landscape.

The Iao Needle, also known in Hawaiian as Kuka‘emoku, is a towering basalt formation created from millennia of erosion and volcanic activity. Unlike the vast shield volcanoes and dramatic cliffs found elsewhere on the islands, the needle’s shape is unique—an emerald spire that juts dramatically from the valley, draped in tropical vegetation and often shrouded by clouds drifting through the West Maui Mountains.

The surrounding valley is part of the West Maui Forest Reserve, an area filled with dense rainforest, waterfalls, and streams. Frequent rain nourishes this fertile region, making it one of the greenest and most vibrant places on Maui. The Iao Stream meanders through the valley, carving a path that has sustained native flora, fauna, and Hawaiian communities for centuries.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-520874214-5f27618a2ebb4a0cb07cee5c70954e75.jpg)

Beyond its natural beauty, the Iao Needle holds deep cultural and historical significance. The valley was once considered sacred, serving as a burial site for Maui’s chiefs, or ali‘i. Because of this, it is regarded as a place of reverence and respect. Visitors are encouraged to tread thoughtfully, keeping in mind the generations of Hawaiian heritage connected to the land.

One of the most famous events tied to Iao Valley is the Battle of Kepaniwai in 1790. This fierce conflict took place during King Kamehameha I’s campaign to unify the Hawaiian Islands under his rule. The battle was fought between Kamehameha’s forces and Maui’s warriors, led by King Kalanikūpule. The fighting was intense and devastating—so much so that the battle’s name, Kepaniwai, means “the damming of the waters,” as the Iao Stream was said to have been clogged with the fallen.

Though the battle ended in a tragic loss for Maui, it marked a pivotal moment in Hawaiian history. The Iao Needle, rising high above the valley, is said to have served as a lookout point during the fighting. Today, the valley is a place of peace, but the echoes of its past remain a reminder of Hawaii’s struggles and resilience.

For travelers to Maui, the Iao Needle is one of the island’s most accessible and rewarding cultural landmarks. Located just a short drive from Wailuku, the Iao Valley State Monument offers visitors a chance to immerse themselves in nature and history in less than an hour’s journey from most resort areas.

The park features a paved, well-maintained trail that leads to a lookout point with sweeping views of the needle and valley. The walk is relatively easy, making it a family-friendly excursion suitable for visitors of all ages. Along the way, interpretive signs provide insight into the area’s cultural and natural history, enriching the experience.

In addition to the main lookout, the park offers pathways along the Iao Stream and through lush gardens showcasing native Hawaiian plants. The air is cool and fresh, often perfumed by tropical flowers, and the constant presence of mist and flowing water creates a tranquil atmosphere. For those who want to go beyond the state monument, nearby hiking trails in the West Maui Mountains offer more challenging adventures.

Like many treasured places in Hawaii, Iao Valley and the Iao Needle require care and respect from both residents and visitors. The site has undergone temporary closures in recent years to allow for restoration and to protect the land from erosion and overuse. Efforts by local organizations and the Hawai‘i State Parks system ensure that the valley remains a living classroom for cultural education and environmental stewardship.

Visitors are reminded to follow all posted guidelines, stay on designated trails, and avoid disturbing the natural and cultural resources. By treating the land with aloha and reverence, we help ensure that the Iao Needle continues to inspire future generations.

The allure of the Iao Needle lies not only in its dramatic appearance but also in the way it symbolizes the connection between Hawaii’s natural beauty and cultural heritage. It is a place where geology, ecology, history, and legend converge. Standing at the lookout, gazing at the spire rising from the valley floor, one cannot help but feel a sense of awe—a reminder of how the Hawaiian Islands were shaped not only by volcanic forces but also by the lives and struggles of the people who called them home.

For visitors to Maui, a journey to the Iao Needle is more than just a photo opportunity. It is an invitation to step into the heart of Hawaii, to listen to the whispers of history in the wind, and to experience a place that has stood as a silent witness to centuries of change.

Hawai‘i State Parks – Iao Valley State Monument

Battle of Kepaniwai Historical Overview

Native Hawaiian Plant Restoration Efforts

1. What exactly is the Iao Needle in Maui?

The Iao Needle is a 1,200-foot tall basalt pinnacle rising out of the lush Iao Valley on Maui. Covered in dense tropical vegetation and surrounded by misty mountains, it’s one of Hawaii’s most famous natural landmarks. Its unique, narrow shape was formed through thousands of years of erosion, making it unlike any other geological feature on the islands.

2. Why is the Iao Needle such a significant natural landmark in Hawaii?

The Iao Needle stands out because of its dramatic appearance and lush green setting. While much of Hawaii is known for volcanoes and cliffs, the needle’s steep, narrow spire is visually striking and instantly recognizable. The surrounding Iao Valley is one of the greenest locations on Maui, fed by constant rainfall, waterfalls, and the flowing Iao Stream. Its untouched beauty makes it a must-see stop for nature lovers.

3. What is the cultural or historical importance of Iao Valley and the Iao Needle?

Iao Valley is deeply sacred in Hawaiian culture. For centuries, it served as a burial ground for Maui’s chiefs (ali‘i), making it a site of reverence. The valley was also the location of the historic 1790 Battle of Kepaniwai, where King Kamehameha I fought to unify the Hawaiian Islands. The Iao Needle is believed to have served as a lookout during the battle. Today, it remains a place where visitors are encouraged to walk with respect and aloha.

4. What was the Battle of Kepaniwai, and how is it connected to the Iao Needle?

The Battle of Kepaniwai was a pivotal conflict in Hawaiian history. King Kamehameha I brought his forces to Maui in 1790, clashing with Maui’s warriors led by King Kalanikūpule. The battle was intense—its name, “Kepaniwai,” means “the damming of the waters,” referencing how the Iao Stream was reportedly blocked by the fallen. The Iao Needle, towering above the battlefield, is said to have served as a strategic vantage point during the fighting.

5. How do I visit the Iao Needle State Monument on Maui?

Visiting the Iao Needle is simple and convenient. Located just minutes from Wailuku and less than an hour from most resort towns, the Iao Valley State Monument features paved walkways, interpretive signs, and a main lookout offering incredible views of the valley and its iconic spire. The walk is easy and family-friendly, making it suitable for all ages and fitness levels.

6. Is there hiking at Iao Valley, and what can I expect on the trails?

Yes—while the main lookout trail is paved and easy, the area offers several paths and walkways that explore the gardens and Iao Stream. The state monument itself is gentle and accessible, while additional trails in the nearby West Maui Mountains offer more challenging adventures for experienced hikers. Expect lush greenery, cool breezes, and the calming sound of flowing water.

7. What should visitors know about preservation and respecting Iao Valley?

Iao Valley is a sacred and environmentally sensitive site. In recent years, it has experienced temporary closures for restoration, erosion control, and cultural preservation. Visitors should stay on marked trails, follow posted guidelines, avoid disturbing wildlife and plants, and treat the area with aloha. Respecting the valley ensures it remains pristine for future generations.

8. Why does the Iao Needle capture the imagination of visitors?

The Iao Needle inspires awe because it represents the perfect blend of Hawaii’s natural beauty and cultural depth. Standing before it, visitors see not just a towering green peak—but a symbol of Hawaii’s geological story, ecological wonder, and rich historical past. Its quiet presence in the valley invites reflection, making it far more than a simple sightseeing stop.

9. Is the Iao Needle worth visiting during my Maui vacation?

Absolutely. The Iao Needle is one of Maui’s most iconic and accessible cultural landmarks. Whether you’re interested in Hawaii’s history, love stunning landscapes, or want a peaceful outdoor escape, the valley offers a meaningful experience for all types of travelers. It’s a quick visit with a big payoff—and ideal for families, photographers, and anyone seeking a deeper connection to Maui’s heritage.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or