The Hawaiian Islands are not only breathtaking landscapes of volcanic peaks, lush rainforests, and endless coastlines; they are also lands alive with stories, chants, and legends passed down for generations. These mo‘olelo (traditional stories) are woven deeply into the fabric of Hawaiian identity, explaining natural phenomena, teaching cultural values, and honoring the sacred relationship between people and the land.

One of the most celebrated figures in Hawaiian mythology is the demigod Māui. Known across Polynesia in many forms, Māui is remembered as a trickster, a hero, and a benefactor of humanity. In Hawaii, his legends are especially tied to the island of Maui, which bears his name. To explore the island without learning the stories of this demigod would be to miss an essential part of its soul.

Māui is not unique to Hawaii—his stories are found throughout Polynesia, from Tahiti to Samoa to Aotearoa (New Zealand). Yet, while the details shift with each culture, he consistently embodies the traits of intelligence, resourcefulness, and mischief. He is often seen as a kupua, a supernatural being with both divine and human qualities, who uses cleverness and courage to challenge nature itself.

In Hawaii, Māui is not considered one of the four primary gods (akua)—Kāne, Kū, Lono, and Kanaloa—but rather a heroic demigod whose actions brought great benefits to humankind. His tales are told not just as entertainment, but as teaching stories filled with lessons about perseverance, balance, and respect for the forces of the natural world.

Perhaps the most famous Hawaiian legend of Māui tells of his battle with the sun. In ancient times, the sun raced across the sky, leaving days too short for people to grow crops, dry their kapa (bark cloth), or prepare food. Māui, determined to help his mother and his people, climbed to the summit of Haleakalā, the massive volcano that dominates the island of Maui.

There, he lay in wait until dawn, crafting ropes from coconut fiber and lashing them with his great strength. When the sun appeared, Māui snared its rays and refused to release them until the sun agreed to slow its journey. The sun relented, granting longer days and blessing humanity with time to live and thrive. Today, visitors to Haleakalā National Park watch the sunrise and recall this powerful story, a reminder of Māui’s triumph and the island’s spiritual depth.

Another story tells of Māui’s magical fishhook, called Manaiakalani. With it, Māui pulled great land masses from the depths of the ocean. In some traditions, it is said that he fished up islands themselves. In Hawaiian legend, this reflects the volcanic creation of new lands rising from beneath the Pacific, linking myth with the geologic truth of the islands’ origins.

Māui’s ingenuity was not limited to the sun and sea. In one tale, he captured the powerful winds that made sailing dangerous. By taming these forces, he allowed Polynesian navigators to voyage more safely across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, ensuring survival and expansion. This legend resonates with Hawaii’s deep voyaging traditions and the revival of navigation by stars, currents, and winds in modern times through groups such as the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Māui’s feats are more than just fantastical tales. They symbolize humanity’s relationship with the natural world and highlight values central to Hawaiian culture:

In this way, Māui reflects the Hawaiian concept of pono—living in balance and righteousness with the world around you.

The island of Maui itself is said to be named after the demigod. Some traditions hold that Māui’s father, Hina, named the island in his honor. Others suggest that the island’s very shape, dominated by Haleakalā’s vast shield volcano, recalls the legends of Māui’s great deeds.

For Hawaiians, this connection is more than symbolic. The island and the demigod are spiritually tied, reminding residents and visitors that Maui is not only a place of natural beauty but also a sacred landscape shaped by story and tradition.

Though centuries have passed, Māui’s stories remain alive. They are shared through oli (chants), hula (dance), and mo‘olelo (oral traditions), connecting each new generation to the wisdom of the past. Cultural practitioners continue to honor these legends as living knowledge, not relics of history.

For visitors, learning about Māui is a way to deepen their experience of the island. Watching the sunrise at Haleakalā, paddling in the ocean, or simply walking the land becomes more meaningful when one understands that these places are alive with history, myth, and spirit.

Māui, the demigod of the Hawaiian island of Maui, embodies the enduring spirit of ingenuity, courage, and connection to nature. His legends—snaring the sun, fishing up islands, and taming the winds—are not only stories of heroism but also reflections of the Hawaiian worldview: that humanity must live in balance with the powerful forces that shape our world.

The island of Maui, bearing his name, is both a geographical wonder and a cultural treasure. To explore it is to step into a landscape where myth and reality blend, where every sunrise recalls an ancient victory, and where the legacy of Māui continues to inspire those who walk upon his island.

1. Who is Māui in Hawaiian mythology?

Māui is a heroic demigod celebrated across the Hawaiian Islands for his cleverness, bravery, and contributions to humanity. Although not one of the four major Hawaiian gods, Māui appears in countless mo‘olelo (traditional stories) as a kupua—someone with both divine and human qualities. His feats often help people, such as slowing the sun, controlling the winds, and raising land from the ocean. These Hawaiian legends highlight values of resourcefulness, respect for nature, and the importance of living in balance.

2. How is Māui connected to the island of Maui?

The island of Maui is said to be named after the demigod. Some stories say Māui’s mother, Hina, gave the island his name; others say the island’s shape and rugged volcanic features reflect his legendary deeds. For many Hawaiians, this connection is more than symbolic—the island and the hero share spiritual importance. Visiting Maui while learning about Māui deepens your understanding of the land, culture, and history woven into the island.

3. Is Māui found only in Hawaiian stories?

No—Māui is a prominent figure throughout Polynesia. His legends appear in places such as Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, and Aotearoa (New Zealand). While each region tells different versions of his stories, Māui consistently appears as a clever, mischievous, and heroic figure. In Hawaii specifically, the tales emphasize his ability to help humanity and teach lessons about perseverance and harmony with nature.

4. What is the story of Māui snaring the sun on Haleakalā?

One of the most famous Hawaiian legends tells how Māui slowed the sun to give people longer days. According to the story, days were once too short for cooking, fishing, and kapa-making, so Māui climbed to the summit of Haleakalā with strong ropes made from coconut fiber. When the sun rose, he snared its rays and refused to release them until the sun agreed to move more slowly. Today, watching sunrise at Haleakalā National Park is a powerful reminder of this legendary feat.

5. What is Māui’s magical fishhook, and what did he do with it?

Māui’s fishhook, Manaiakalani, is central to one of his most famous exploits. Hawaiian legends say Māui used the fishhook to pull land from the depths of the ocean. In some Polynesian traditions, he fished up islands themselves. This myth beautifully mirrors Hawaii’s real volcanic origins—new land rising from the sea—blending science with storytelling and cultural meaning.

6. What does the legend of Māui controlling the winds teach us?

In this lesser-known story, Māui captures and tames powerful winds that once made ocean voyaging difficult and dangerous. By controlling these winds, he allowed ancient Polynesian navigators to travel more safely across vast distances. This legend highlights Hawaii’s deep ocean-voyaging heritage and emphasizes how Māui symbolizes guidance, navigation, and human connection to natural forces.

7. What values or lessons do Māui’s legends teach?

The stories of Māui illustrate several core Hawaiian values:

These lessons continue to guide Hawaiian cultural practices and storytelling today.

8. Why are Hawaiian legends and mo‘olelo so important?

Hawaiian mo‘olelo are more than myths—they are cultural maps, teaching tools, and historical records that explain natural phenomena, honor ancestors, and preserve knowledge. These stories connect Hawaiians to their land, values, and identity. Learning these legends helps visitors appreciate the islands not just as destinations, but as living cultural landscapes filled with meaning and history.

9. How is Māui’s legacy preserved in Hawaii today?

Māui’s stories are kept alive through oli (chants), hula (dance), and oral storytelling traditions. Cultural practitioners, educators, and families continue to share these legends as living knowledge. When visitors explore places like Haleakalā, paddle along the coast, or walk the land, they are stepping into spaces shaped by both volcanic history and the stories of Māui that still echo across the island.

10. Do these legends add meaning to visiting Maui as a tourist?

Absolutely. Learning about Māui before or during your trip adds depth to every experience—sunrise at Haleakalā becomes a connection to an ancient legend, island landscapes become reminders of volcanic creation stories, and even the ocean winds feel tied to ancestral navigation. Understanding the demigod’s role in Hawaiian culture enriches your visit and helps you appreciate Maui as a sacred, storied island.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Hawaiʻi is often celebrated for its beaches, volcanoes, and lush rainforests, but the islands are also home to one of the most fascinating bird communities in the world. Due to their isolation in the middle of the Pacific, Hawaiʻi’s birds evolved in unique ways, creating species found nowhere else on Earth. From jewel-toned honeycreepers to soaring seabirds, the avifauna of Hawaiʻi is as diverse as it is fragile.

This blog explores the rich world of Hawaiian birds—their history, ecological role, cultural importance, and the ongoing efforts to protect them.

Roughly five million years ago, a single finch-like bird made its way to the Hawaiian Islands. Over millennia, this ancestor gave rise to an astonishing radiation of species known today as the Hawaiian honeycreepers. With beaks adapted to specific foods—from nectar to seeds to insects—these birds became a striking example of adaptive evolution. Their plumage is equally remarkable, ranging from bright reds and yellows to subtle greens and browns.

Unfortunately, many of these species are now extinct, and many of the survivors are critically endangered. Yet those that remain provide a living window into evolution’s creativity.

The ʻiʻiwi is perhaps the most recognizable of Hawaiʻi’s native birds. With scarlet feathers, black wings, and a gracefully curved bill, it feeds primarily on the nectar of native ʻōhiʻa lehua blossoms. Once widespread across all islands, the ʻiʻiwi is now mostly found at higher elevations, where mosquitoes that carry avian malaria are less common.

Another nectar-feeding honeycreeper, the ʻapapane thrives in ʻōhiʻa forests and is known for its loud, complex song. Though still relatively common, it plays an important ecological role as a pollinator.

Resilient and adaptable, the Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi is one of the few native birds showing resistance to avian malaria. Its olive-yellow feathers and versatility in feeding—nectar, insects, and fruits—have helped it persist even as other species decline.

Deeply significant in Hawaiian culture, the ʻalalā was once considered a guardian spirit and messenger. Sadly, it became extinct in the wild in the early 2000s, though captive breeding and reintroduction programs are ongoing. The ʻalalā is highly intelligent, known for using tools and complex vocalizations.

The only hawk native to Hawaiʻi, the ʻio is found only on the Big Island. Revered in Hawaiian tradition as an embodiment of royalty and a messenger of the gods, the ʻio is a powerful predator that soars over forests and open fields alike.

While forest birds often capture attention, Hawaiʻi’s seabirds are equally extraordinary. The islands provide nesting grounds for millions of seabirds that roam the Pacific.

Not all birds in Hawaiʻi are native. Humans have introduced species such as the common myna, zebra dove, and house sparrow, which are now among the most commonly seen in towns and cities. While these birds add to the islands’ avian diversity, some compete with native species for food and nesting sites.

For Native Hawaiians, birds are deeply intertwined with tradition, art, and spirituality. The vibrant feathers of species like the ʻiʻiwi and ʻōʻō were once used to create royal cloaks and helmets, symbols of mana (spiritual power) and authority. Birds also appear in chants, legends, and proverbs, serving as guides, protectors, and omens.

The ʻio, for instance, was seen as a protector of chiefs, while the ʻalalā was viewed as a voice of the forest, bridging the human and spiritual realms.

Hawaiʻi is often called the “extinction capital of the world.” Since human arrival, more than half of the islands’ bird species have vanished. The primary threats today include:

Conservation efforts are underway to protect the remaining species. Strategies include mosquito control programs, captive breeding and reintroduction of endangered birds, and habitat restoration. Organizations and agencies are working tirelessly to ensure that Hawaiʻi’s unique birds continue to thrive for generations to come.

The birds of Hawaiʻi are more than just beautiful creatures—they are storytellers of evolution, stewards of native ecosystems, and cultural treasures. Whether watching an ʻiʻiwi dart among ʻōhiʻa blossoms, listening to the haunting call of a shearwater, or spotting an ʻio soaring above the Big Island, one cannot help but feel a deep connection to the land and its living heritage.

Protecting these birds is not only about conservation—it is about preserving the soul of Hawaiʻi itself.

1. Why are Hawaiian birds so unique compared to birds elsewhere in the world?

Hawaiian birds are incredibly unique because the islands’ remote location allowed species to evolve in isolation for millions of years. A single finch-like ancestor led to the creation of the famous Hawaiian honeycreepers—birds with dramatically different beak shapes, colors, and feeding habits. Many Hawaiian birds are endemic, meaning they exist nowhere else on Earth, making them some of the rarest and most remarkable birds on the planet.

2. What are Hawaiian honeycreepers, and why are they so important?

Hawaiian honeycreepers are a group of native birds that evolved from one common ancestor around five million years ago. Through adaptive evolution, these birds developed specialized beaks to eat nectar, seeds, insects, and fruits. Their vibrant colors—from reds and yellows to greens—make them some of the most striking birds in Hawaiʻi. Honeycreepers are essential pollinators in native forests and are a living example of evolution’s creativity.

3. Which native Hawaiian birds should visitors look out for?

Some of the most notable native Hawaiian birds include:

These species represent Hawaiʻi’s natural heritage and ecological diversity.

4. What seabirds and shorebirds can be found in Hawaiʻi?

Hawaiʻi is home to impressive seabirds and waterbirds, including:

Many seabirds nest in colonies on remote islands or steep cliffs, making Hawaiʻi a crucial habitat for Pacific bird populations.

5. Are all the birds in Hawaiʻi native?

No—many birds in Hawaiʻi are introduced species brought by humans over the past 200 years. Common urban birds like mynas, zebra doves, and house sparrows are not native. While they add to the visual diversity of the islands, some introduced species compete with native birds for food and nesting areas, creating conservation challenges.

6. Why are so many Hawaiian birds endangered or extinct?

Hawaiʻi is known as the extinction capital of the world, and sadly, many native birds have disappeared. The main threats include:

These factors create difficult conditions for native species, especially honeycreepers that rely on high-elevation forests.

7. What conservation efforts are being made to protect Hawaiian birds?

Conservation in Hawaiʻi is extensive and ongoing. Efforts include:

8. What role do birds play in Hawaiian culture and tradition?

Birds are deeply woven into Hawaiian culture. Feathers from birds like the ʻiʻiwi and ʻōʻō were once used to create royal cloaks and helmets, representing mana (spiritual power). Birds also appear in Hawaiian chants, mythology, and proverbs. For example:

Birds symbolize connection, protection, and the natural balance that is central to Hawaiian identity.

9. Where can visitors see native Hawaiian birds in the wild?

Some of the best places to see native Hawaiian birds include:

These areas protect native forests where honeycreepers and other endemic species still thrive.

10. Why is protecting Hawaiian birds so important?

Protecting Hawaiian birds means preserving Hawaiʻi’s ecology, culture, and history. These birds pollinate forests, control insects, and reflect the islands’ evolutionary heritage. They carry cultural meaning and connect Hawaiians to their ancestral past. Saving them is about more than conservation—it’s about keeping the spirit and identity of Hawaiʻi alive for future generations.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

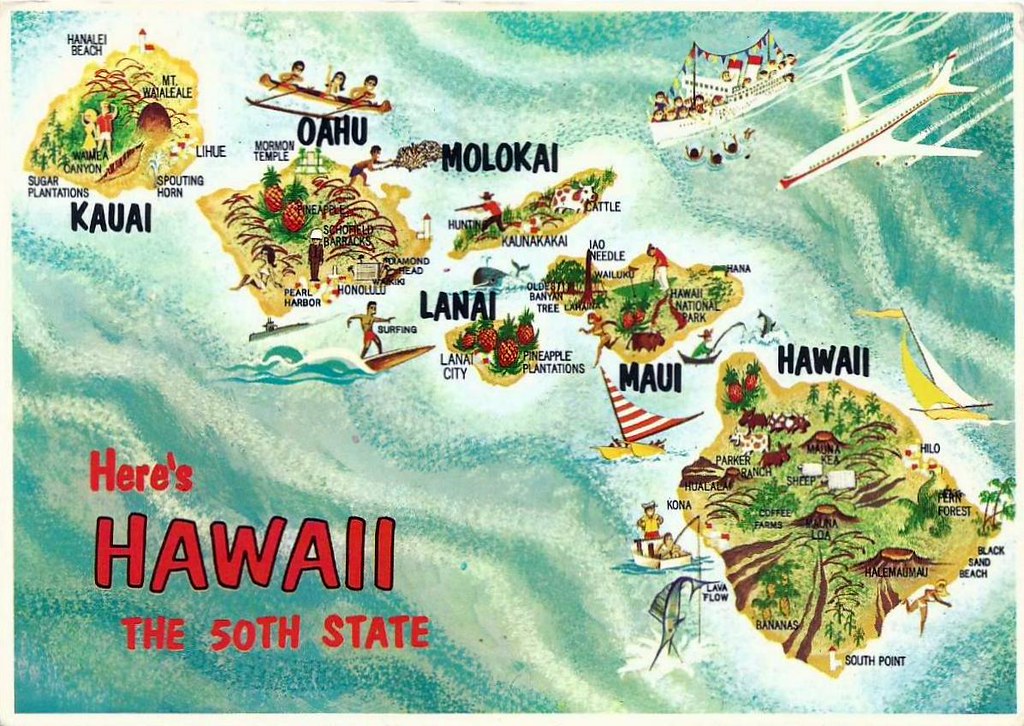

The Hawaiian Islands are known worldwide for their beauty, culture, and aloha spirit—but behind each island’s name lies a story rooted in history, language, and tradition. Some names are tied to Hawaiian gods and legends, others to early explorers and migrations, and still others to natural features that inspired their titles. Understanding how Hawai‘i’s islands got their names offers a deeper appreciation for the archipelago’s cultural and linguistic heritage.

The largest island in the chain, Hawai‘i Island, shares its name with the entire state. According to Hawaiian tradition, the name comes from Hawai‘iloa, a legendary Polynesian navigator credited with discovering the islands. Some oral histories suggest Hawai‘iloa named the island after himself, while others connect the word Hawai‘i to the ancestral homeland of the Polynesians, Hawaiki, a place referenced in oral traditions across the Pacific.

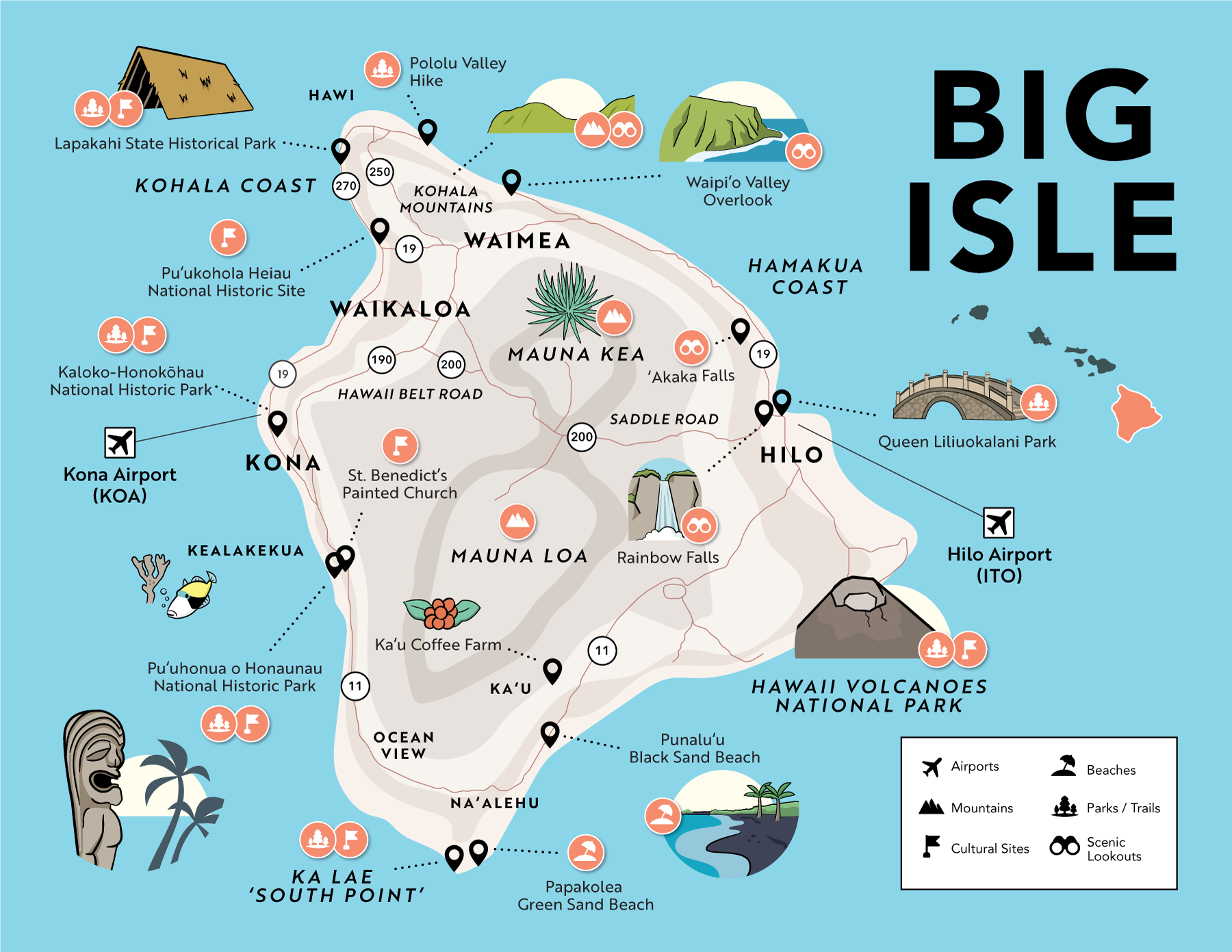

Because of its size, Hawai‘i Island is often called “The Big Island” to avoid confusion with the state name. Its vast landscapes, from active volcanoes to snow-capped Mauna Kea, make it a fitting bearer of the archipelago’s central name.

Learn more about Hawai‘i Island

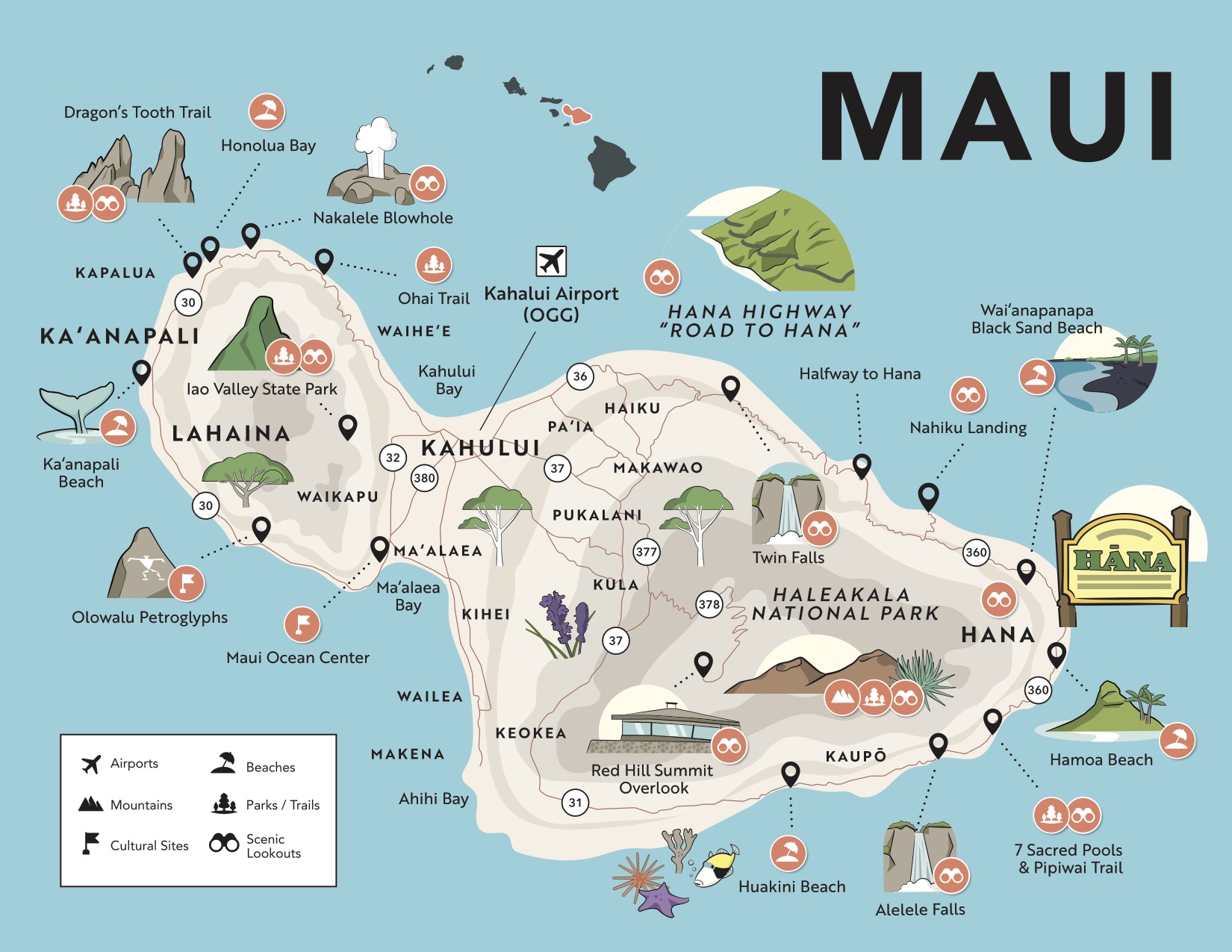

The island of Maui is named after the demigod Māui, a heroic figure common in Polynesian mythology. In Hawaiian lore, Māui is famous for his strength and cleverness—he is said to have fished the islands out of the sea and slowed the sun to give humanity longer days.

Some traditions say the island was named by the navigator Hawai‘iloa in honor of his son, who was named after the demigod. The association between the island and this cultural hero makes Maui a land of legendary stature.

Explore Maui’s history

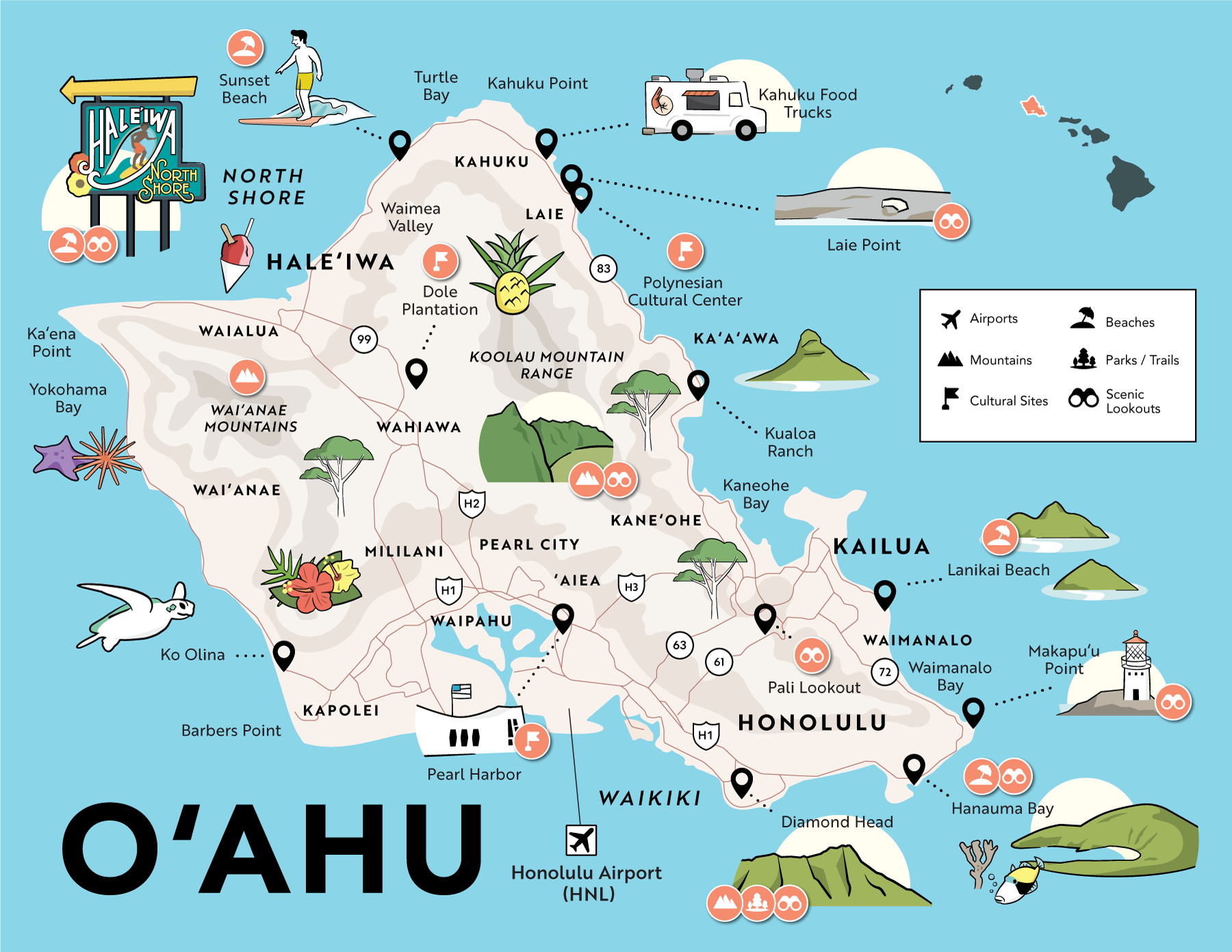

O‘ahu translates to “The Gathering Place,” though its exact origins are less clear than some other islands. The name appears in Hawaiian oral traditions and songs, but no definitive explanation exists. Some suggest that O‘ahu was named by Hawai‘iloa after one of his relatives.

True to its title, O‘ahu has always been a gathering place—it is home to Honolulu, the state capital, and the majority of Hawai‘i’s population today. With historic sites like Pearl Harbor and cultural landmarks such as ʻIolani Palace, O‘ahu remains a center of both ancient and modern Hawaiian life.

More on O‘ahu’s culture

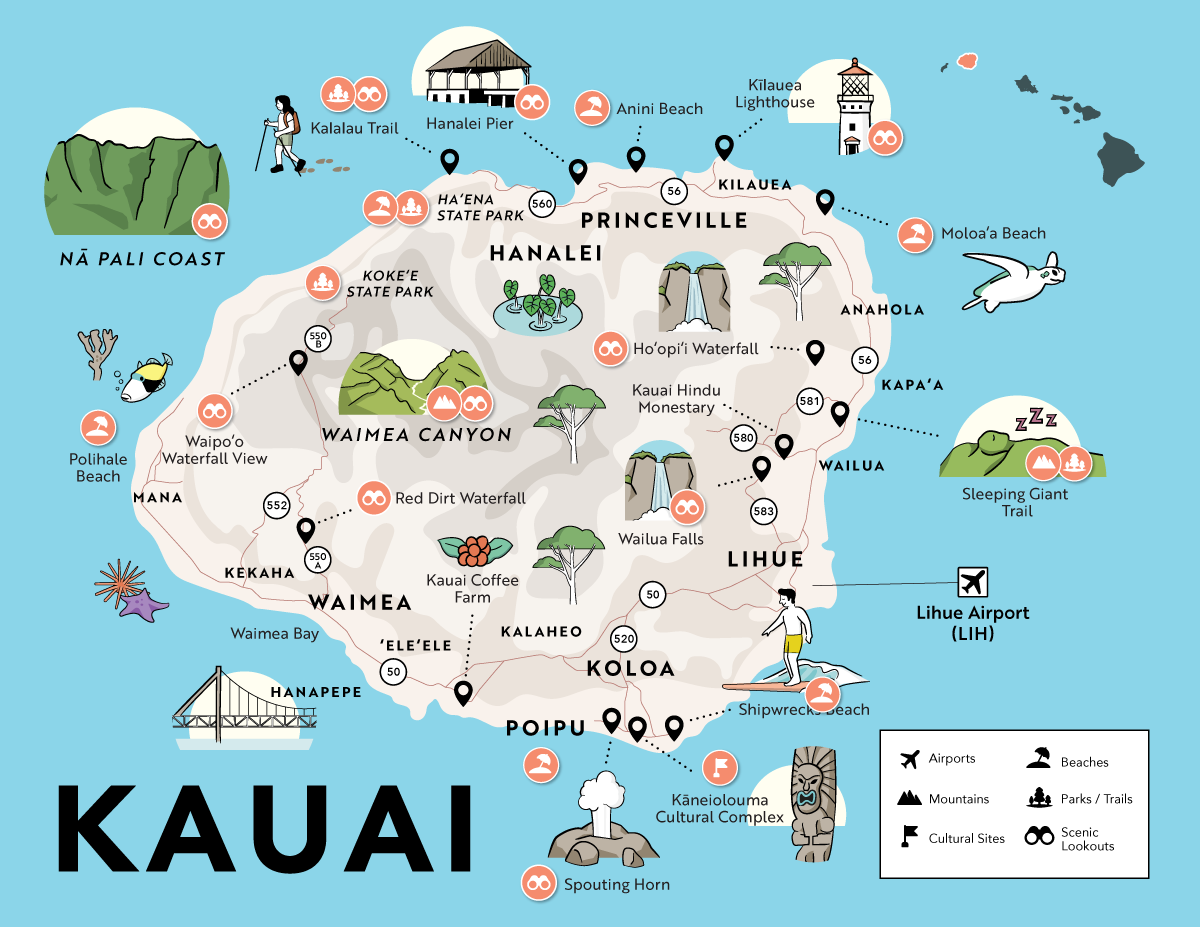

Kaua‘i, often called the “Garden Island,” may derive its name from the Hawaiian word kau (to place) and a‘i (to eat). Some interpret this as “a place around the neck,” referencing the island’s shape. Others link it to legends of Hawai‘iloa, who is said to have named the island after his son.

Kaua‘i is the oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands geologically, and its name reflects a deep connection to family and tradition. Its lush mountains and valleys give it a timeless, almost mystical quality, matching the poetic beauty of its name.

Discover Kaua‘i

Known as the “Friendly Isle,” Moloka‘i is deeply tied to Hawaiian culture. It is home to Kalaupapa, the historic settlement where Saint Damien and Saint Marianne cared for people with Hansen’s disease (leprosy), and it is regarded as a place where traditional Hawaiian practices remain strong.

Learn more about Moloka‘i

Lāna‘i is often called the “Pineapple Isle,” but its traditional name is said to mean “day of conquest.” According to legend, the island was once inhabited by spirits until a Maui chief’s son, Kaululā‘au, banished them and claimed the island for people. Another interpretation ties the name to lā (day) and na‘i (conquer), reflecting the conquest of these spirits.

In modern times, Lāna‘i was famous for its pineapple plantations, once producing most of the world’s pineapples. Today it is known for its quiet landscapes and luxury resorts.

Explore Lāna‘i

The privately owned island of Ni‘ihau has a name with uncertain origins. Some suggest it means “snatched away,” possibly referring to its creation in myth when it was pulled from the sea. Others connect it to words meaning “withered” or “dry,” reflecting its arid climate.

Ni‘ihau is unique as the “Forbidden Island,” closed to most visitors, and it is one of the last places where Hawaiian is spoken as the primary language.

Learn more about Ni‘ihau

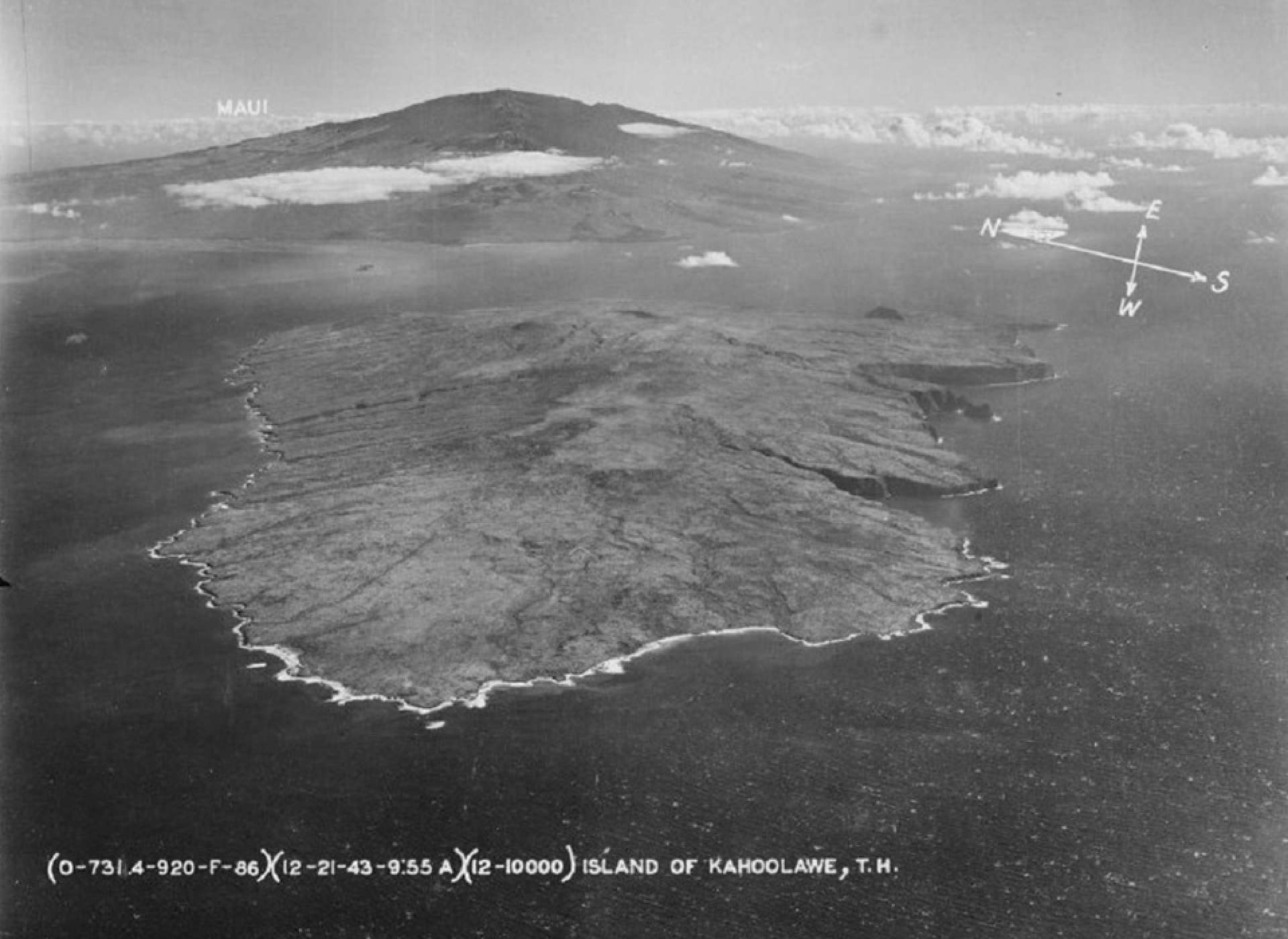

The smallest of the main islands, Kaho‘olawe, is named for its natural environment. Known as "The Target Isle" as it was used as a bombing target practice for the United States military during World War II.

Kaho‘olawe has a turbulent modern history, as it was used by the U.S. military for bombing practice during World War II and afterward. Today, it is uninhabited and managed by the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission, dedicated to cultural and ecological restoration.

Learn about Kaho‘olawe

The names of Hawai‘i’s islands are not just labels—they are living reminders of legends, family ties, and natural features. They connect modern residents and visitors to the islands’ ancient past and help preserve the Hawaiian language and worldview.

When you say Maui or Kaua‘i, you are invoking the names of gods, ancestors, or poetic descriptions of the land itself. Recognizing the origins of these names adds depth to any journey across Hawai‘i and reinforces the importance of respecting the culture that continues to thrive here.

1. How did the Hawaiian Islands get their names?

Each Hawaiian island’s name reflects a mix of legend, language, history, and geography. Some names come from Hawaiian gods and demigods, such as Maui; others come from ancient Polynesian navigators like Hawai‘iloa; and some connect to natural features or poetic descriptions. These names preserve Hawai‘i’s ancestral stories and offer deeper insight into the culture and worldview of Native Hawaiians.

2. Why is Hawai‘i Island called “The Big Island”?

Hawai‘i Island shares its name with the entire state, so people call it “The Big Island” to avoid confusion. According to tradition, the island’s name comes from Hawai‘iloa, a legendary navigator who discovered the archipelago. Some stories say he named the island after himself, while others link the name to Hawaiki, the ancestral homeland referenced across Polynesia.

3. Why is the island of Maui named after the demigod Māui?

Maui is named after Māui, the iconic Polynesian demigod known for slowing the sun and pulling islands from the sea. Some legends say Hawai‘iloa named the island after his son, who was named in honor of the demigod. This connection gives the Valley Isle a strong tie to myth and heroic tradition.

4. What does the name O‘ahu mean?

O‘ahu is often translated as “The Gathering Place.” While its exact linguistic origin isn’t fully documented, the name appears frequently in chants, oral histories, and ancient stories. Fittingly, O‘ahu is still the “gathering place” today as the home of Honolulu, Waikīkī, and the majority of Hawai‘i’s population.

5. Where does the name Kaua‘i come from?

The origin of Kaua‘i is not completely certain. One interpretation links its name to kau (to place) and a‘i (to eat), while another ties it to Hawai‘iloa’s son. As the oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands, Kaua‘i’s poetic name reflects its deep roots in family tradition, age-old legends, and the island’s lush, mystical landscapes.

6. What is the meaning behind the name Moloka‘i?

Moloka‘i, known as “The Friendly Isle,” holds a strong cultural and spiritual history. Its name’s origin is debated, but the island itself remains closely tied to Hawaiian traditions, including storytelling, farming, fishing, and historical sites like Kalaupapa, where Saint Damien and Saint Marianne cared for people with Hansen’s disease.

7. Why is Lāna‘i called “the Pineapple Isle,” and what does its name originally mean?

Lāna‘i earned the nickname “The Pineapple Isle” thanks to its once-massive pineapple plantations. Traditionally, however, the name Lāna‘i is said to mean “day of conquest.” Legend says a Maui chief’s son, Kaululā‘au, drove away spirits from the island, making it suitable for human settlement.

8. What is the meaning of Ni‘ihau’s name?

The exact meaning of Ni‘ihau is uncertain. Some legends interpret it as “snatched away,” referencing mythological creation stories, while others translate it as “withered” or “dry,” reflecting its arid environment. Today, Ni‘ihau is known as “The Forbidden Island,” privately owned and known for its preservation of Hawaiian language and culture.

9. Why is Kaho‘olawe considered sacred, and how did it get its name?

Kaho‘olawe’s name is often linked to its natural environment, with some translations meaning “the carrying away” or connected to storms and dryness. It is considered sacred by Native Hawaiians and has been the focus of significant cultural and ecological restoration after decades of military use. Today, it is uninhabited and protected by the Kaho‘olawe Island Reserve Commission.

10. Why do the names of Hawai‘i’s islands matter so much?

The names of Hawai‘i’s islands are more than geographic labels—they are living reflections of culture, language, genealogy, and spirituality. Knowing their meanings helps visitors appreciate the islands on a deeper level and encourages respect for Hawaiian traditions. When you say names like Maui or Kaua‘i, you’re speaking words rooted in ancient stories and cultural identity.

11. How can learning the meanings of Hawaiian island names enhance my visit?

Understanding each island’s name deepens your connection to the places you explore. Whether visiting Maui’s legendary landscapes, Kaua‘i’s ancient valleys, or O‘ahu’s historic sites, the stories behind the names enrich your experience and help you travel with greater respect for Hawai‘i’s culture and heritage.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

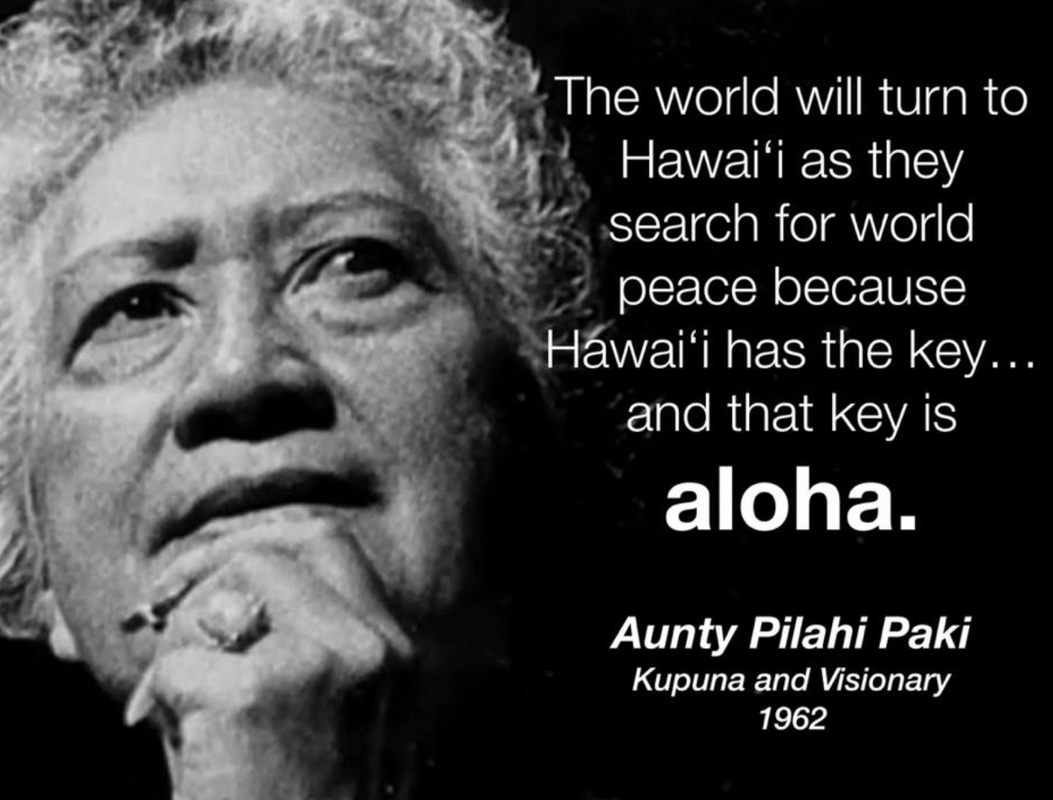

When people think of Hawai‘i, the word Aloha often comes to mind. Tourists hear it upon arrival and departure, see it printed on souvenirs, and may even adopt it as a casual greeting. But to those who live in Hawai‘i or understand Hawaiian culture, Aloha is much more than a word—it is a way of life, a profound philosophy, and a spiritual connection to others and to the land.

In its most basic usage, Aloha means both "hello" and "goodbye," but this simple translation does not capture the essence of the word. Rooted in Native Hawaiian values, Aloha expresses love, compassion, mercy, respect, and unity. It is a sacred word that reflects the deep cultural and spiritual beliefs of the Hawaiian people.

The word Aloha is composed of two parts: "Alo" meaning presence, front, or face, and "ha" meaning breath of life. When said in its full context, Aloha can be interpreted as “the presence of divine breath” or “to share the breath of life.” In ancient Hawai‘i, the traditional greeting involved touching foreheads and exchanging a breath (honi), symbolizing this shared life force. Saying Aloha isn't just a polite phrase; it's an acknowledgment of the sacred life energy that flows through and connects all beings.

Native Hawaiian scholar and cultural practitioners have long emphasized that Aloha is a guiding principle. It is an ethical code of conduct built on mutual respect and care for one another. The Aloha Spirit—a term frequently used in Hawai‘i—is about living in harmony with yourself, with others, and with nature. It encourages kindness, patience, and understanding, even in difficult situations.

The Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s helped revive many traditional values, including the philosophy of Aloha. Today, many Hawaiian elders (kupuna) and educators pass this teaching on, emphasizing that living with Aloha is an ongoing practice of humility (ha‘aha‘a), harmony (lokahi), and compassion (aloha kekahi i kekahi—love one another).

Interestingly, Hawai‘i is the only U.S. state with a law explicitly recognizing a cultural value. In Section 5-7.5 of the Hawai‘i Revised Statutes, the Aloha Spirit is formally recognized as a guiding principle for public officials. This law encourages government leaders and citizens alike to treat one another with care, respect, and love, using Aloha as a basis for decision-making and daily interaction.

Here’s an excerpt from the statute:

“Aloha is more than a word of greeting or farewell or a salutation. Aloha means mutual regard and affection and extends warmth in caring with no obligation in return.”

This demonstrates just how deeply rooted the concept of Aloha is in the social fabric of the islands.

Another important dimension of Aloha is its relationship with nature, especially the land—ʻāina. In Hawaiian belief, the land is not a resource to be exploited, but a family member to be cared for and respected. The phrase Aloha ʻĀina means “love of the land,” and it encapsulates a deep sense of responsibility and stewardship for Hawai‘i’s natural environment.

Many Hawaiian activists and cultural practitioners use Aloha ʻĀina to express their commitment to protecting sacred spaces, preserving ecosystems, and fighting for the sovereignty of the land. Whether it's resisting overdevelopment, advocating for clean water, or restoring native plants, these efforts are grounded in the spiritual and cultural imperative of Aloha.

To live with Aloha means practicing it daily—not only with friends and family, but also with strangers, coworkers, and even adversaries. It is being mindful of how one’s actions affect others, choosing empathy over judgment, and approaching life with gratitude.

Simple acts like:

…are all ways of embodying Aloha.

And it’s not limited to those who live in Hawai‘i. The principles of Aloha can be practiced by anyone, anywhere. In a world often driven by division and competition, Aloha offers a powerful reminder of our shared humanity.

Aloha is not just a word; it's a worldview. It calls us to be present, to act with compassion, and to live in alignment with nature and each other. Whether you're visiting Hawai‘i for the first time or have lived there your whole life, understanding the deeper meaning of Aloha can enrich your experience and connection to this special place.

Let’s not just say Aloha—let’s live it.

If you enjoyed learning about Aloha, consider exploring other core Hawaiian values like ʻohana (family), pono (righteousness), and malama (to care for). Each of these values interweaves with Aloha to create the spiritual and cultural richness that makes Hawai‘i truly unique.

1. What does the word Aloha actually mean in Hawaiian?

Aloha is often translated as “hello” and “goodbye,” but its true meaning goes much deeper. In Hawaiian culture, Aloha represents love, compassion, respect, kindness, and connection. Linguistically, “Alo” means presence or face, and “ha” means breath of life—so Aloha can be understood as “the presence of divine breath.” It reflects the Hawaiian belief that we are all connected through shared life energy.

2. Why is Aloha considered more than just a greeting?

Aloha is much more than a casual phrase—it is a cultural philosophy and way of life. For Native Hawaiians, Aloha is a guiding principle rooted in compassion, humility, harmony, and mutual respect. It’s a reminder to treat others with kindness and to be mindful of how one’s actions impact the world. Living with Aloha means approaching life with gratitude, patience, and empathy every day.

3. What is the traditional Hawaiian greeting involving breath?

The traditional greeting is called honi, where two people touch foreheads and noses to exchange a shared breath, or ha. This practice symbolizes unity, respect, and the acknowledgment of each other’s life force. Honi reflects the deeper meaning of Aloha—recognizing the sacred breath that connects all living beings.

4. What is the “Aloha Spirit,” and why is it important?

The Aloha Spirit is the cultural value system behind the word Aloha. It encourages living with openness, kindness, humility (haʻahaʻa), harmony (lokahi), and love for others (aloha kekahi i kekahi). It’s about choosing compassion even in difficult situations. The Aloha Spirit shapes how people interact in Hawai‘i, making the islands renowned for warmth, generosity, and peaceful living.

5. Is the Aloha Spirit really written into Hawaii state law?

Yes! Hawai‘i is the only U.S. state with a law recognizing a cultural value. In Hawai‘i Revised Statutes Section 5-7.5, the Aloha Spirit is formally acknowledged as a guiding principle for public officials and government workers. The law states that Aloha means mutual regard, affection, and warm caring without expectation of return. This highlights how deeply Aloha is embedded in everyday life and governance.

6. What does Aloha ʻĀina mean?

Aloha ʻĀina translates to “love of the land.” In Hawaiian culture, the land—ʻāina—is not a resource but a family member to be respected and protected. Aloha ʻĀina expresses a deep responsibility to care for nature, safeguard sacred places, and preserve Hawai‘i’s ecosystems. It also ties to cultural movements advocating sovereignty, environmental justice, and sustainable stewardship.

7. How can visitors to Hawai‘i live with Aloha during their stay?

Visitors can embrace Aloha by practicing kindness, respecting local culture, and caring for the land. Simple actions include:

8. Can people outside of Hawai‘i practice Aloha in their daily lives?

Absolutely. Aloha is universal. Anyone, anywhere can live with Aloha by choosing patience over frustration, empathy over judgment, gratitude over entitlement, and respect over conflict. Aloha is a reminder that human connection, kindness, and compassion make the world better no matter where you are.

9. How does Aloha relate to Hawaiian cultural identity today?

Aloha remains a cornerstone of Hawaiian identity. It influences relationships, traditions, spirituality, and community values. Through language revitalization, cultural education, and the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, the deeper meaning of Aloha continues to thrive. For many, Aloha represents both cultural pride and a spiritual responsibility to care for people and place.

10. Why is understanding the true meaning of Aloha important for visitors?

Understanding Aloha helps visitors connect more respectfully and deeply with the islands. Knowing that Aloha is not just a word—but a value system rooted in love, unity, and mindfulness—encourages travelers to appreciate Hawai‘i beyond the beaches. It enhances their experience and promotes responsible travel that honors local culture, land, and community.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Kīlauea, one of the most active volcanoes on Earth, is a central geological and cultural landmark on Hawaiʻi Island, also known as the Big Island. Its frequent eruptions and dynamic landscape have not only sculpted the island's physical terrain but also shaped the spiritual and cultural identity of Hawaiʻi’s people. Revered in Hawaiian mythology as the home of Pele, the goddess of volcanoes and fire, Kīlauea embodies both creation and destruction. This remarkable volcano is more than just a natural wonder—it is a living, breathing force that continues to evolve.

Kīlauea is a shield volcano, meaning it has broad, gentle slopes built up by the flow of low-viscosity lava over time. It began forming approximately 210,000 to 280,000 years ago and emerged above sea level about 100,000 years ago. Geologists believe it is fed by the Hawaiian hotspot, a plume of superheated material rising from deep within the Earth’s mantle.

Unlike stratovolcanoes like Mount St. Helens, Kīlauea’s eruptions are typically non-explosive, allowing lava to spread gradually across vast areas. This contributes to the continuous growth of the Big Island, making it the youngest and largest of the Hawaiian Islands.

Kīlauea has a rich and often unpredictable eruption history. It has erupted nearly continuously from 1983 to today, largely from the Puʻu ʻŌʻō vent along its East Rift Zone. This 40-year eruption changed the island’s topography significantly, adding new landmass, destroying hundreds of homes, and creating dramatic lava flows that drew scientists and visitors from around the world.

The most significant modern eruption occurred in 2018, beginning in the lower Puna district. Massive fissures opened, emitting lava that engulfed entire neighborhoods, reshaped the coastline, and displaced over 2,000 residents. Simultaneously, the summit caldera at Halemaʻumaʻu collapsed, dropping over 1,600 feet and creating a massive crater. The eruption released substantial amounts of sulfur dioxide gas, impacting air quality and visibility across the island.

After a pause, volcanic activity resumed in December 2020, with periodic summit eruptions within Halemaʻumaʻu crater, creating a lava lake that continues to captivate scientists and tourists alike. As of 2025, Kīlauea remains under close observation by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), with minor seismic activity, gas emissions, and deformation suggesting magma remains close to the surface.

In Native Hawaiian culture, Kīlauea is sacred. It is believed to be the home of Pele, the fiery goddess of volcanoes. According to Hawaiian legends, Pele resides in Halemaʻumaʻu crater and is responsible for the eruptions that shape the land. Her presence is respected and revered; many locals leave offerings at the crater's edge in honor of her power.

This cultural reverence highlights a deep connection between the Hawaiian people and their environment. Rather than viewing volcanic activity as purely destructive, it is often seen as part of the natural cycle of life, death, and renewal—a force that creates as much as it consumes.

Today, Kīlauea is a major attraction within Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, drawing over a million visitors annually. Tourists can view the active crater from safe distances, explore hiking trails, walk through lava tubes, and observe how volcanic forces continually reshape the landscape.

Some of the most popular sites include:

Visitors are advised to check eruption updates and park alerts before visiting, as conditions can change rapidly. The National Park Service and the USGS provide detailed, real-time information to ensure visitor safety and environmental protection.

https://www.nps.gov/havo/index.htm

Kīlauea is one of the most studied volcanoes in the world. Scientists monitor seismic activity, ground deformation, gas emissions, and thermal imagery to forecast eruptions and ensure public safety. The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), established in 1912, is the lead agency responsible for monitoring Kīlauea and other Hawaiian volcanoes.

Recent research efforts include using drones for high-resolution imaging, deploying sensors around the caldera, and employing artificial intelligence to detect patterns in volcanic behavior. These innovations have greatly improved eruption forecasting and hazard mitigation.

While Kīlauea’s eruptions can be destructive, they also play a critical ecological role. Lava creates new habitats over time, and pioneering species like ʻōhiʻa lehua trees and ferns begin to colonize the barren rock. Over decades, these new lands evolve into thriving ecosystems.

Additionally, lava flows that reach the ocean expand the coastline and create new underwater environments rich in marine life. Despite the short-term devastation, the volcano contributes to the long-term renewal and biodiversity of the island.

Kīlauea is more than just a volcano—it is a living monument to the dynamic forces that have built and continue to shape the Hawaiian Islands. Its eruptions, while sometimes destructive, also symbolize renewal, resilience, and reverence. Whether you are a geologist, traveler, or cultural enthusiast, a visit to Kīlauea offers insight into the raw power of nature and the enduring spirit of the Hawaiian people.

1. What makes Kīlauea one of the most active volcanoes in the world?

Kīlauea is considered one of the world’s most active volcanoes because it has erupted frequently for centuries, including a nearly continuous eruption from 1983 to 2018. It sits directly over the Hawaiian hotspot, where magma rises steadily from deep beneath the Earth. As a shield volcano, its low-viscosity lava flows easily, creating ongoing volcanic activity that constantly reshapes the Big Island.

2. How old is Kīlauea, and how did it form?

Kīlauea began forming between 210,000 and 280,000 years ago, emerging above sea level roughly 100,000 years ago. It developed as the Pacific Plate moved over the Hawaiian hotspot, causing repeated lava flows that gradually built the volcano’s broad, sloping shield shape. Today, it continues to grow as new lava is added to the landscape.

3. What is significant about Kīlauea’s eruption history?

Kīlauea has had many major eruptions, but the most notable modern events include:

Kīlauea’s eruptions are monitored closely, as they can change quickly and dramatically.

4. Why is Kīlauea culturally significant to Native Hawaiians?

In Hawaiian tradition, Kīlauea is the home of Pele, the goddess of volcanoes and fire. Pele is believed to reside in Halemaʻumaʻu crater, and her power is both respected and revered. Many Hawaiians leave offerings for her, honoring her as the creator and destroyer of land. This cultural connection reflects a deep respect for the natural cycles of creation, destruction, and renewal.

5. Is it safe to visit Kīlauea today?

Yes—Kīlauea is safe to visit when guidelines are followed. The volcano is located within Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, where trails, roads, and viewing areas are designed to keep visitors at safe distances. However, conditions can change quickly. Always check National Park Service alerts, eruption updates, and air-quality reports before your visit:

https://www.nps.gov/havo/index.htm

6. What are the best places to view Kīlauea and its volcanic features?

Popular viewing and exploration sites include:

These locations highlight both the destructive and creative forces of Kīlauea.

7. What happened during the 2018 Kīlauea eruption?

In 2018, Kīlauea experienced one of its most dramatic eruptions in history. Large fissures opened in the lower Puna district, releasing massive lava flows that destroyed over 700 homes, covered roads, and formed new coastline. At the summit, the Halemaʻumaʻu crater collapsed, deepening by more than 1,600 feet. The eruption reshaped the Big Island’s geography and demonstrated the immense power of Hawaiian volcanism.

8. How do scientists monitor Kīlauea?

Kīlauea is monitored by the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), one of the most advanced volcano monitoring systems in the world. Scientists use:

These technologies help forecast eruptions, improve safety, and advance volcanic research.

9. How does volcanic activity contribute to Hawaiʻi’s ecosystem?

Although eruptions can be destructive, Kīlauea also plays a vital role in creating new environments. Fresh lava forms new land that is gradually colonized by pioneer species like ʻōhiʻa lehua and ferns. Over decades, this process leads to thriving forests and habitats. Lava entering the ocean also forms new underwater ecosystems, contributing to the island’s long-term ecological renewal.

10. What is it like to visit Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park?

Visitors can expect dramatic volcanic landscapes, steam vents, old lava flows, scenic drives, and world-class hiking. Popular experiences include:

It’s one of the most unique national parks on Earth, where geology and culture blend seamlessly.

11. Why is Kīlauea important to Hawaiʻi’s identity?

Kīlauea symbolizes creation, resilience, and cultural heritage. Its eruptions shape the land, influence Hawaiian stories, and strengthen the connection between people and place. For both residents and visitors, experiencing Kīlauea offers a deeper understanding of the power that formed the Hawaiian Islands and continues to transform them today.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Sitting peacefully in the Pacific Ocean between Maui and Lanaʻi lies Kaho'olawe, a small, windswept island that holds profound cultural and spiritual significance for Native Hawaiians. Known traditionally as Kanaloa, the island is revered as a sacred place of navigation, worship, and connection to ancestral lineage. However, during and after World War II, Kaho'olawe was subjected to decades of relentless bombing and military testing by the United States Navy—leaving behind physical devastation, cultural loss, and environmental trauma that reverberates to this day.

Kaho'olawe's tragic transformation began in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. As fears of Japanese invasion heightened, the U.S. military sought secure and remote locations to conduct training exercises and weapons testing. Kaho'olawe, sparsely populated and largely uninhabited due to its arid environment, was deemed ideal.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order placing Kahoʻolawe under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy. Soon after, the island became a training ground for ship-to-shore bombardment, aerial strafing, amphibious landings, and live-fire target practice. It was systematically pounded by explosives, including high-powered bombs, napalm, and eventually, during the Cold War era, simulated nuclear weapons.

While the island was always considered sacred to Native Hawaiians, its importance was largely ignored by military authorities during this period. Ancient heiau (temples), archaeological sites, and burial grounds were destroyed or damaged beyond recognition. The impact on the island’s fragile ecosystem was similarly catastrophic—vegetation was stripped, topsoil eroded, and entire areas became craters of scorched earth.

Though World War II ended in 1945, Kaho'olawe's suffering continued. The island was never returned to the people of Hawaiʻi. Instead, it became a permanent part of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet training operations, continuing to be bombed for decades under the rationale of military preparedness.

By the 1970s, amidst a broader Hawaiian Renaissance—a cultural movement focused on the revival of Native Hawaiian identity, language, and sovereignty—activists began to challenge the military’s occupation of the island. A grassroots group called Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) was formed in 1976, led by passionate cultural leaders such as George Helm and Kimo Mitchell. They called for an end to the bombing, the return of the island, and the restoration of its land and sacredness.

PKO’s movement drew national attention. Members of the group staged a series of high-risk occupations by secretly landing on the island to draw attention to its plight. Tragedy struck in 1977 when George Helm and Kimo Mitchell disappeared at sea during an attempt to reach Kaho'olawe—sacrifices that would galvanize support and intensify the movement.

Here is a YouTube video link that showcases some of the bomb test footage from those years:

After years of protest, lawsuits, and growing public scrutiny, the U.S. Navy finally ceased live-fire training exercises in 1990, under orders from President George H. W. Bush. Four years later, in 1994, the island was officially transferred back to the State of Hawaiʻi, though it remained under a federal mandate for cleanup.

Congress authorized $400 million for the cleanup effort, known as the Kahoʻolawe Island Conveyance Commission (KICC) project. However, the task was enormous. The U.S. Navy had turned Kahoʻolawe into one of the most extensively bombed islands in the Pacific, and a large portion of the island was still littered with unexploded ordnance (UXO)—including deep-buried munitions that posed long-term hazards.

The goal was to clear at least 100% of the surface and 25% of the subsurface, but due to the dangers and complexities involved, only about 75% of the surface and less than 10% of the subsurface were deemed safe by the time cleanup efforts officially ended in 2003. Much of the island remains off-limits for public access due to these lingering dangers.

The legacy of the bombings on Kahoʻolawe is multifaceted—environmental, cultural, and spiritual. The island’s landscape remains scarred by craters, eroded gullies, and large swaths of lifeless land. Its already arid climate, compounded by decades of deforestation and explosive impacts, has made ecological recovery a daunting task.

Culturally, the loss was immeasurable. Ancient stone structures, petroglyphs, and sacred sites were damaged or destroyed. For many Hawaiians, this represented not just a loss of physical artifacts, but a severing of spiritual ties to the land and ancestors.

However, the movement to reclaim and restore Kahoʻolawe has sparked a cultural rebirth. Since the return of the island, restoration efforts have included planting native species, controlling erosion, and reviving traditional practices. Kahoʻolawe is now managed by the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC), which oversees access and stewardship of the island for cultural, educational, and environmental purposes.

Only Native Hawaiians or those involved in official restoration efforts are permitted to visit, and overnight stays are highly regulated. These visits often include ceremonies, chants (oli), and work to heal the land—both symbolically and physically.

Today, Kahoʻolawe stands as both a symbol of the destructive impacts of militarization and a testament to the resilience of Native Hawaiian culture. It is a living example of how cultural identity, once suppressed and overlooked, can rise again through collective effort, remembrance, and aloha ʻāina—a deep love for the land.

The island’s story continues to inspire movements across Hawaiʻi and beyond, calling attention to the long-term effects of colonization, environmental degradation, and the need for Indigenous stewardship. While Kaho'olawe may never be fully restored to its former self, its journey from devastation to renewal is a powerful reminder that healing is possible—through time, effort, and a commitment to honoring the past.

To Learn More:

These organizations continue the vital work of healing Kaho'olawe and keeping its history alive for future generations.

1. What is Kahoʻolawe, and why is it important to Native Hawaiians?

Kahoʻolawe is a small island located between Maui and Lānaʻi, traditionally known as Kanaloa, named after the Hawaiian god of the ocean and navigation. For Native Hawaiians, the island is a sacred cultural and spiritual site, used historically for navigation training, ceremonies, and ancestral connection. Its significance lies not only in its history but also in its role as a symbol of cultural identity, resilience, and aloha ʻāina (love of the land).

2. Why did the U.S. military bomb Kahoʻolawe during World War II and afterward?

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. Navy seized Kahoʻolawe for military training, citing its remote location and sparse population. For decades, the island was used for live-fire bombing, naval shelling, amphibious landings, napalm tests, and Cold War–era simulated nuclear detonations. The military continued using the island long after WWII, claiming ongoing training needs—even though it was a culturally sacred and ecologically fragile place.

3. How did the bombing affect Kahoʻolawe’s land and cultural sites?

The bombing caused severe environmental and cultural destruction. Explosions stripped vegetation, eroded topsoil, and created deep craters. Sacred heiau (temples), petroglyphs, and burial sites were damaged or destroyed. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) remains buried beneath the ground, making large parts of the island unsafe and inaccessible. This devastation disrupted the island’s ecosystem and severed generations of cultural ties.

4. Who started the movement to stop the bombing of Kahoʻolawe?

In the 1970s, during the Hawaiian cultural renaissance, a group called Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) emerged to stop the military occupation. Led by cultural activists including George Helm and Kimo Mitchell, PKO launched a grassroots resistance movement that included protests, legal action, and dangerous landings on the island. Their courage brought national awareness to the cause and became a turning point in restoring Hawaiian cultural pride.

5. When did the military stop bombing Kahoʻolawe?

Live-fire bombing officially ended in 1990 under President George H. W. Bush. In 1994, the island was transferred back to the State of Hawaiʻi, but cleanup efforts continued for years due to the extensive unexploded ordnance left behind. Though military activity has ceased, the scars and hazards remain.

6. Was Kahoʻolawe fully cleaned up after the military left?

No. Despite a $400 million cleanup effort, only about 75% of the island’s surface and less than 10% of its subsurface were cleared of unexploded ordnance. Deeply buried munitions make some areas permanently off-limits. Full restoration is impossible, but ongoing efforts work toward safety, ecological recovery, and cultural renewal.

7. Can you visit Kahoʻolawe today?

Kahoʻolawe is not open to the general public. Access is restricted due to dangerous unexploded ordnance and its designation as a cultural reserve. Only Native Hawaiians or individuals participating in official restoration, cultural, or educational missions through the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) are allowed to visit. Overnight stays require permits and follow strict protocols.

8. What is the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC)?

KIRC is the state agency responsible for protecting, restoring, and managing Kahoʻolawe. Their work includes erosion control, native plant restoration, cultural practices, and environmental monitoring. KIRC aims to fulfill the vision of Kahoʻolawe as a center for cultural education, traditional navigation, and ecological healing.

9. What role does Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) play today?

PKO remains deeply involved in the island’s restoration and cultural revival. They continue to lead ceremonies, cultural training, advocacy, environmental projects, and educational programs. PKO’s work keeps the history, sacrifices, and legacy of Kahoʻolawe alive for future generations.

10. How has the bombing affected Kahoʻolawe’s environment long-term?

Decades of explosives caused extreme ecological damage. The island suffers from:

Despite these challenges, native plants are slowly returning, and large-scale efforts continue to heal the land. Kahoʻolawe is a powerful example of environmental trauma—and resilience.

11. Why is Kahoʻolawe considered a symbol of Hawaiian resistance?

Kahoʻolawe represents the painful impacts of militarization and colonization, but also the strength of Hawaiians who fought to reclaim it. The island embodies the values of aloha ʻāina, cultural revival, environmental guardianship, and unity. Its story continues to inspire Indigenous movements across Hawaiʻi and the Pacific.

12. How can I learn more or support Kahoʻolawe’s restoration?

You can learn more or support restoration efforts through these organizations:

Volunteering, donating, or sharing Kahoʻolawe’s story helps ensure the island’s healing continues.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

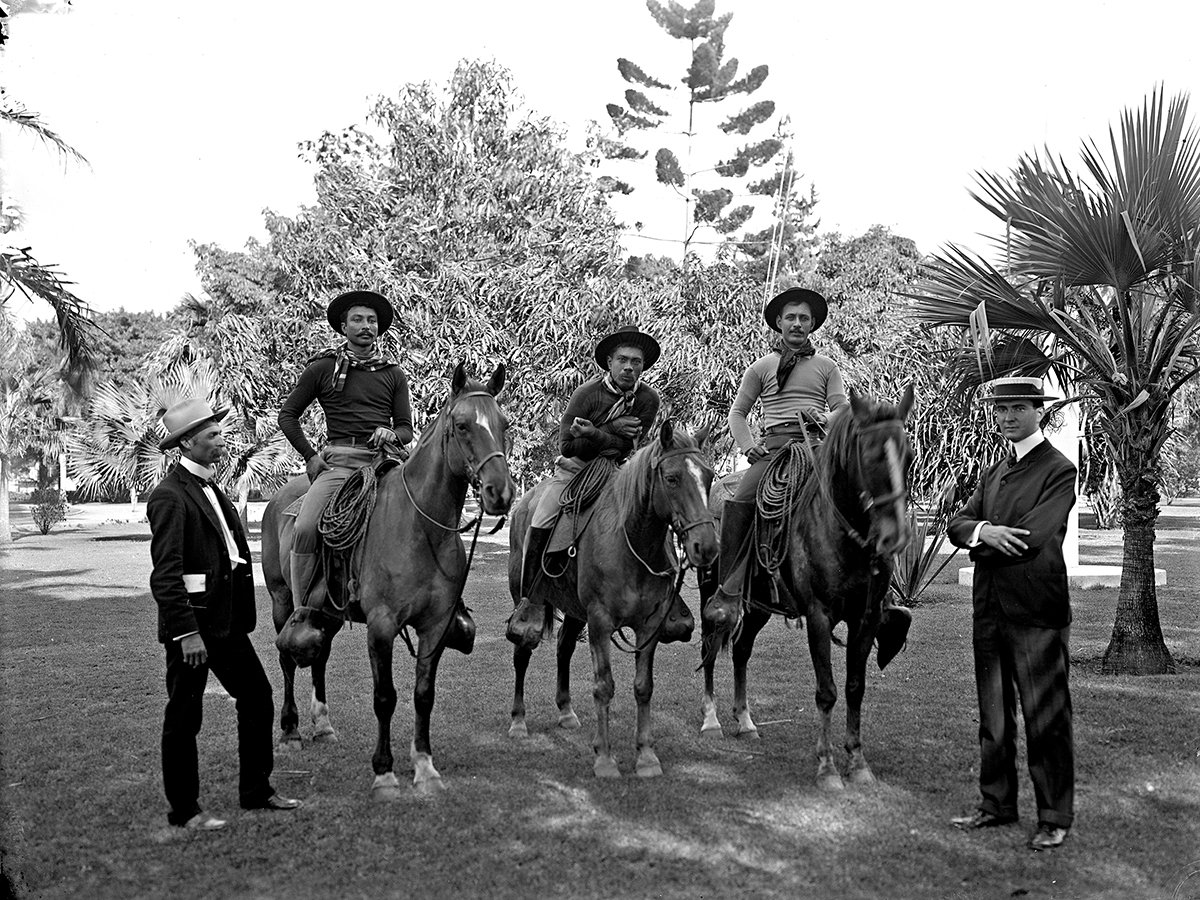

In the misty uplands of Waimea, through the rolling pastures of Molokaʻi, and across the sprawling ranches of upcountry Maui, a powerful legacy lives on—that of the paniolo, Hawaii’s cowboys. While many recognize them for their rugged horsemanship and contributions to island ranching, few understand the depth of their impact on Hawaiian identity. Beyond wrangling cattle and riding horseback, the paniolo were instrumental in preserving Hawaiian language and culture during one of the most turbulent eras in the islands' history.

The story begins in the early 19th century. After British explorer George Vancouver gifted cattle to King Kamehameha I in the 1790s, those animals multiplied unchecked, becoming a growing threat to farmland and forests. To manage the explosive cattle population, Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli) invited experienced Mexican vaqueros—Spanish-speaking cowboys from California—to the Hawaiian Islands in the 1830s.

These vaqueros brought with them expertise in ranching, roping, saddle-making, and horsemanship. Hawaiian men were quick learners, absorbing these new skills and adapting them to their own environment. Over time, the Hawaiian term paniolo, believed to derive from “Español,” came to represent this new breed of cowboy—one who blended Hawaiian tradition with Mexican technique.

But the influence of these vaqueros ran deeper than the physical skills they taught. They shared a way of life grounded in respect for the land, strong family ties, music, and storytelling—values that mirrored those in traditional Hawaiian society. The result was not just a new profession, but a new cultural identity: the paniolo, proud stewards of the land (kuleana) and protectors of Hawaiian spirit.

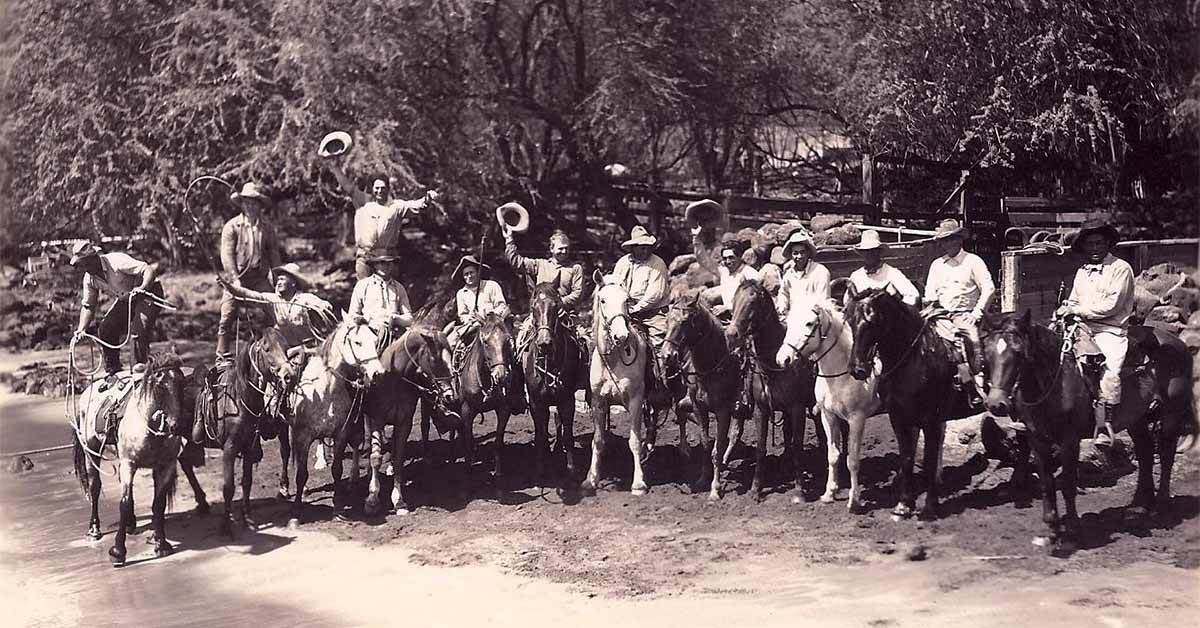

While the paniolo helped birth a thriving ranching economy, their most profound contribution may have come decades later, when Hawaiian identity faced near erasure.

Following the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and the subsequent annexation by the United States in 1898, sweeping changes were forced upon the islands. In 1896, Hawaiian was banned as a language of instruction in schools. Speaking the language in public was discouraged or outright punished sometimes, punishable by death. English-only policies became a tool of cultural suppression, designed to assimilate Native Hawaiians into Western norms.

In cities and towns, this pressure took its toll. Hawaiian children were discouraged from speaking their mother tongue, and generations began to grow up without fluency in their native language. But in the countryside—on the remote ranches of Hawaiʻi Island, Molokaʻi, and Maui—the story was different.

The paniolo lived far from government centers and urban control. On the ranches, Hawaiian remained the language of daily life. Cowboys spoke Hawaiian in the fields, at home, in song, and in prayer. Oral traditions, chants (oli), and ancestral knowledge were passed from parent to child without interruption. These ranchlands became cultural sanctuaries, where Hawaiian identity endured in spite of official efforts to silence it.

The paniolo didn’t set out to be activists or revolutionaries—they simply lived according to the values of their ancestors. In doing so, they kept the language alive when it was outlawed. They kept aloha ʻāina—love of the land—at the core of their daily lives. They upheld ʻohana—family—and the importance of story and song. And perhaps most powerfully, they maintained a sense of pride in being Hawaiian, even when the dominant culture tried to erase it.

The legacy of the paniolo endures today not just through ranching, but through rodeo culture, which remains vibrant in rural Hawaiʻi. These events—held annually in towns like Makawao, Waimea, and Kaunakakai—are more than just competitions. They are celebrations of identity, where Hawaiian language is spoken freely, and traditions are proudly displayed.

Slack-key guitar and mele paniolo (cowboy songs) echo through the air, telling stories of hardship, humor, and heritage. Rodeos serve as modern spaces where Hawaiian values and community thrive—further testament to the paniolo’s role in cultural preservation.

If you are interested in booking tickets or more information on the Makawao Rodeo here are links to booking, etc.

Bookings: oskiericeeeventcenter.com

Information: https://bossfrog.com/makawao-rodeo/general/

When the Hawaiian Renaissance began in the 1970s—a movement aimed at restoring language, culture, and sovereignty—it found that the roots had never been fully lost. In part, that was thanks to the paniolo. The oral language, still spoken fluently by many elder cowboys, became a lifeline for linguists and educators rebuilding curriculum for Hawaiian language immersion schools. The values embedded in paniolo life—self-reliance, stewardship, and storytelling—matched perfectly with the goals of the movement.

Today, many Hawaiian immersion programs and cultural centers recognize the contribution of paniolo families in preserving the language. Elders who once roped cattle are now seen as cultural heroes—unintentional but vital defenders of Hawaiian heritage during a time of crisis.

The story of the paniolo is not just about cattle or cowboy hats. It’s about resilience. It’s about a group of people who, through quiet strength and cultural pride, preserved a language and identity that others tried to erase. The legacy of the Mexican vaqueros lives on through them, but the spirit of the paniolo is deeply, undeniably Hawaiian.

So next time you hear a cowboy song in Hawaiian, see a young rider at a rodeo, or visit the open pastures of upcountry Maui, remember: you're witnessing the continuation of a legacy that refused to be silenced.

1. Who are the paniolo, and why are they important in Hawaiian history?

The paniolo are Hawaiian cowboys whose legacy dates back to the early 19th century. Beyond managing cattle and ranchlands, they played a major role in preserving Hawaiian language and culture during times of political upheaval. Their traditions, values, and everyday use of Hawaiian kept the language alive when it was suppressed in schools and public spaces.

2. How did the paniolo tradition begin in Hawaii?

The paniolo story began when Mexican vaqueros were brought to Hawaiʻi in the 1830s to help control the growing cattle population gifted to King Kamehameha I. These vaqueros taught Hawaiians horsemanship, roping, ranching, and saddle-making. Hawaiians mastered these skills quickly and adapted them to local environments, creating a unique cowboy culture now known as the paniolo tradition.

3. Why is the word “paniolo” often linked to the Spanish word “Español”?

Many historians believe the word paniolo comes from the Hawaiian pronunciation of “Español,” reflecting the Mexican and Spanish-speaking origins of the first vaqueros who trained Hawaiian cowboys. Over time, paniolo became a proud Hawaiian term representing a cowboy lifestyle grounded in both Mexican technique and Hawaiian values.

4. How did the paniolo help preserve the Hawaiian language?

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, after the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, laws and public pressure suppressed the Hawaiian language—especially in cities and schools. But on remote ranches across Maui, Molokaʻi, and the Big Island, the paniolo continued speaking Hawaiian daily, passing it down through families. Ranchlands became safe havens where the language—and cultural practices—survived despite official bans.

5. What role did rodeos play in Hawaiian cowboy culture?

Rodeos in places like Makawao, Waimea, and Kaunakakai became community hubs where paniolo showcased their roping skills, horsemanship, and cultural pride. Rodeo grounds remain spaces where Hawaiian language, slack-key guitar, cowboy songs (mele paniolo), and local traditions thrive. These events help keep the paniolo spirit alive and visible today.

A popular event is the Makawao Rodeo:

Bookings – https://oskiericeeeventcenter.com

Info – https://bossfrog.com/makawao-rodeo/general/

6. How did paniolo culture influence Hawaiian music and storytelling?

The paniolo blended Mexican musical traditions with Hawaiian rhythms, creating mele paniolo, or cowboy songs—an important part of Hawaiian music history. These songs share stories of ranch life, love, hardship, and humor. Paniolo families also passed down oral traditions, chants (oli), and prayers that became cultural lifelines during the Hawaiian Renaissance and modern language revival.

7. What impact did the Mexican vaqueros have on Hawaiian culture?

The Mexican vaqueros brought more than ranching skills—they introduced:

These values aligned with Hawaiian principles like aloha ʻāina (love of the land) and kuleana (responsibility), helping blend both cultures into the paniolo identity.

8. Where can I experience paniolo culture on my Hawaii trip?

You can experience true paniolo heritage at:

These places offer rodeos, museums, horseback riding, historical tours, and authentic cultural experiences.

9. How did the paniolo contribute to the Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1970s?

When the Hawaiian Renaissance sought to revive Hawaiian language and culture, the paniolo became crucial knowledge keepers. Elder cowboys—many of whom still spoke fluent Hawaiian—helped linguists, educators, and immersion schools rebuild the language that had been nearly lost. Their stories, chants, and values influenced Hawaiian cultural restoration.

10. What makes paniolo culture different from mainland cowboy traditions?

Paniolo culture has its own distinct identity shaped by:

The paniolo are not just cowboys—they are cultural stewards who combine ranching with deep Hawaiian values and history.

11. Why are the paniolo still celebrated today?

The paniolo symbolize resilience, cultural pride, and survival. They kept Hawaiian identity alive during a time of suppression, helped preserve the language, and contributed to today’s cultural revival. Their legacy continues through rodeos, ranching families, schools, and Hawaiian storytelling traditions. They remain an essential—and beloved—part of Hawaii’s history.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

Language is more than a means of communication—it is a reflection of culture, history, and identity. Nowhere is this more evident than in Hawaii, where a unique form of English-based creole known as "Pidgin" has evolved over the past century. Officially referred to as Hawai‘i Creole English, Pidgin is a rich, dynamic language that encapsulates the multicultural heritage of the islands. Its development is deeply tied to Hawaii's complex social, economic, and cultural history, particularly during the plantation era. Today, while sometimes misunderstood, Pidgin remains a vital and expressive part of local identity.

The roots of Pidgin in Hawaii can be traced back to the mid-19th century, during a period of significant immigration and economic transformation. Following the decline of the whaling industry, Hawaii shifted toward an agricultural economy dominated by sugarcane and pineapple plantations. These plantations required a large labor force, which led to an influx of workers from China, Japan, Portugal, Korea, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and other parts of the world.

These immigrant groups, each speaking their own languages, had to find ways to communicate with one another and with English-speaking plantation owners. This necessity gave birth to a rudimentary contact language—an early form of Pidgin—that incorporated vocabulary primarily from English, with grammatical influences from Hawaiian, Japanese, Portuguese, Cantonese, and other languages. At this stage, the language was not yet fully developed or standardized; it functioned mainly as a tool for basic communication.

Over time, as immigrant families settled and generations were born and raised in Hawaii, Pidgin evolved from a simple trade language into a fully developed creole. By the early 20th century, children growing up in multilingual communities began acquiring Pidgin as their first language. This generational shift marked the transformation from a pidgin (a simplified language used for specific purposes) into a creole (a native language with its own stable grammar and vocabulary). For example, instead of saying "He is going to the store," a Pidgin speaker might say, "He stay going store.", another example is many here in Hawaii will say "close the light", instead of "Turn off the light.

Here is a short video talking about the origins of pidgin in Hawaii:

Here is a website that features some of the most common pidgin terms used in Hawaii:

For many in Hawaii, Pidgin is more than a way of speaking—it is an expression of local identity and solidarity. It reflects shared history, values, and a sense of place. It often carries nuances and cultural references that are difficult to translate into standard English. As such, Pidgin is commonly used in informal settings, storytelling, comedy, local literature, and even political discourse to connect authentically with local audiences.

Pidgin is a linguistic treasure that tells the story of Hawaii’s multicultural roots and the resilience of its people. Born out of necessity, shaped by diversity, and sustained by community, it continues to thrive as a powerful marker of identity and cultural pride. As public understanding and appreciation grow, Pidgin stands as a testament to Hawaii’s rich linguistic tapestry—one that deserves both recognition and respect.

Explore the history, language, and cultural importance of Hawai‘i Creole English through these curated resources:

1. What exactly is Pidgin in Hawaii? Is it a real language?

Yes—Hawaii Pidgin is a real, fully developed language, officially called Hawaiʻi Creole English. It began as a communication tool on sugar and pineapple plantations and eventually evolved into a creole spoken natively by many local residents. While rooted in English vocabulary, Pidgin has its own grammar, pronunciation, rhythm, and rules, making it a legitimate language, not “broken English.”

2. How did Pidgin start in Hawaii?

Pidgin emerged in the mid-1800s during the plantation era, when immigrant workers from Japan, China, Portugal, the Philippines, Korea, Puerto Rico, and other regions needed a common way to communicate. They blended English words with Hawaiian, Portuguese, Japanese, Cantonese, and other linguistic influences—creating the earliest form of Pidgin. This language helped bridge the communication gap between workers, overseers, and landowners.

3. How did Pidgin become Hawaiʻi Creole English?

Over time, children born into multilingual plantation communities began learning Pidgin as their first language. Once a generation grows up speaking a pidgin as its native tongue, it transitions into a creole—a stable, rule-based language. By the early 20th century, Hawaii’s Pidgin had become Hawaiʻi Creole English, with consistent grammar and a unique sound system.

4. What are some common Pidgin phrases that visitors might hear in Hawaii?

Some popular Pidgin terms include:

Visitors can explore more Pidgin words here:

https://hawaii.com/50-hawaii-pidgin-words-and-terms-visitors-need-to-know/

And hear pronunciations here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3l23vMgg-x0

5. Why is Pidgin so strongly connected to local identity in Hawaii?

Pidgin carries the history of plantation life, multicultural cooperation, and local values. It reflects the humor, resilience, and shared experiences of generations who lived and worked together across Hawaii’s islands. Speaking Pidgin often signals local pride, cultural grounding, and an authentic connection to community. For many locals, it's a symbol of belonging.

6. Is Pidgin still widely spoken in Hawaii today?

Absolutely. Pidgin remains widely spoken in everyday conversation—especially among local families, younger generations, and multicultural communities. While English is used in schools and formal settings, Pidgin thrives in homes, workplaces, surf spots, local shops, comedy, music, and storytelling. It continues to evolve with modern slang and influences.

7. Why do some people misunderstand Pidgin as “incorrect English”?

Because Pidgin uses many English-based words, outsiders sometimes mistake it for “slang” or “incorrect grammar.” In reality, Pidgin follows consistent grammatical rules—they’re just different from Standard American English. Linguists classify Pidgin as one of the world’s most robust English-based creoles, shaped by Hawaii’s unique cultural landscape.

To learn more about its origins, here’s a quick video:

https://youtube.com/shorts/wNW-7Gq-Lyc?si=1wcbgyn21IWB4zR1

8. Can understanding Pidgin help visitors connect better with locals?

Yes! Even learning a few phrases can show locals that you appreciate Hawaii’s cultural uniqueness. While visitors shouldn’t imitate Pidgin in a mocking or exaggerated way, understanding the basics helps you feel more connected and respectful. It also enhances your travel experience—Pidgin is a doorway into Hawaii’s multicultural history and sense of community.

9. Is Pidgin taught or studied in schools?

While Pidgin is not typically a formal medium of instruction, it is studied academically in linguistics, cultural studies, and Hawaiian history courses. Some educators incorporate Pidgin literature, poetry, and storytelling to engage students. Pidgin has even appeared in official materials, local news stories, and public service announcements.

10. Why is Pidgin an important part of Hawaii’s cultural heritage?

Pidgin is a living reminder of Hawaii’s diverse plantation roots, where immigrants from around the world worked side by side. It symbolizes unity, resilience, and the ability of diverse cultures to blend into something entirely new. Today, Pidgin continues to preserve humor, identity, music, pride, and aloha spirit in a way no other language can.

Pidgin isn’t just something people speak—it’s something they feel.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or

On August 21, 1959, Hawaii officially became the 50th state of the United States. This landmark event marked the culmination of a long and complex history involving indigenous sovereignty, strategic military importance, cultural transformation, and political negotiation. While the date of statehood is straightforward, the story behind how Hawaii became a state is anything but simple. Understanding Hawaii’s path to statehood requires a deeper look into its monarchy, its annexation, its role in American defense strategy, and the political movements of the 20th century.

Before becoming a U.S. state, Hawaii was an independent and internationally recognized sovereign nation. The Hawaiian Kingdom was established in 1795 under King Kamehameha I, who unified the Hawaiian Islands into a single kingdom. Over the next several decades, the Kingdom of Hawaii maintained its independence, signed treaties with major world powers, and even had diplomatic missions abroad.

This period of sovereignty saw the development of a complex governmental system, a constitution, and a thriving multicultural society. However, Hawaii’s strategic location in the Pacific and its fertile lands made it increasingly attractive to foreign powers, particularly the United States.

In 1893, the sovereign Kingdom of Hawai‘i was overthrown in a coup d’état orchestrated by a small group of American and European business interests, with the support of the U.S. Minister to Hawai‘i and U.S. Marines. Queen Liliʻuokalani, Hawai‘i’s last reigning monarch, was deposed under duress in an act widely condemned as illegal and unjust.

Despite strong opposition from Native Hawaiians and an official investigation by President Grover Cleveland that acknowledged the illegality of the coup, the provisional government pressed forward. In 1898, the United States annexed Hawai‘i through the Newlands Resolution—a controversial move lacking a treaty of annexation ratified by the U.S. Senate or the consent of the Hawaiian people.

This chapter in history remains a source of deep pain and protest. In 1993, on the 100th anniversary of the overthrow, the U.S. government formally apologized through the Public Law 103-150 (the "Apology Resolution"), acknowledging that the overthrow was unlawful and that the Native Hawaiian people never relinquished their claims to sovereignty.

The legacy of this event continues to influence Hawaiian identity, cultural preservation, and calls for justice and self-determination today.