Table of Contents

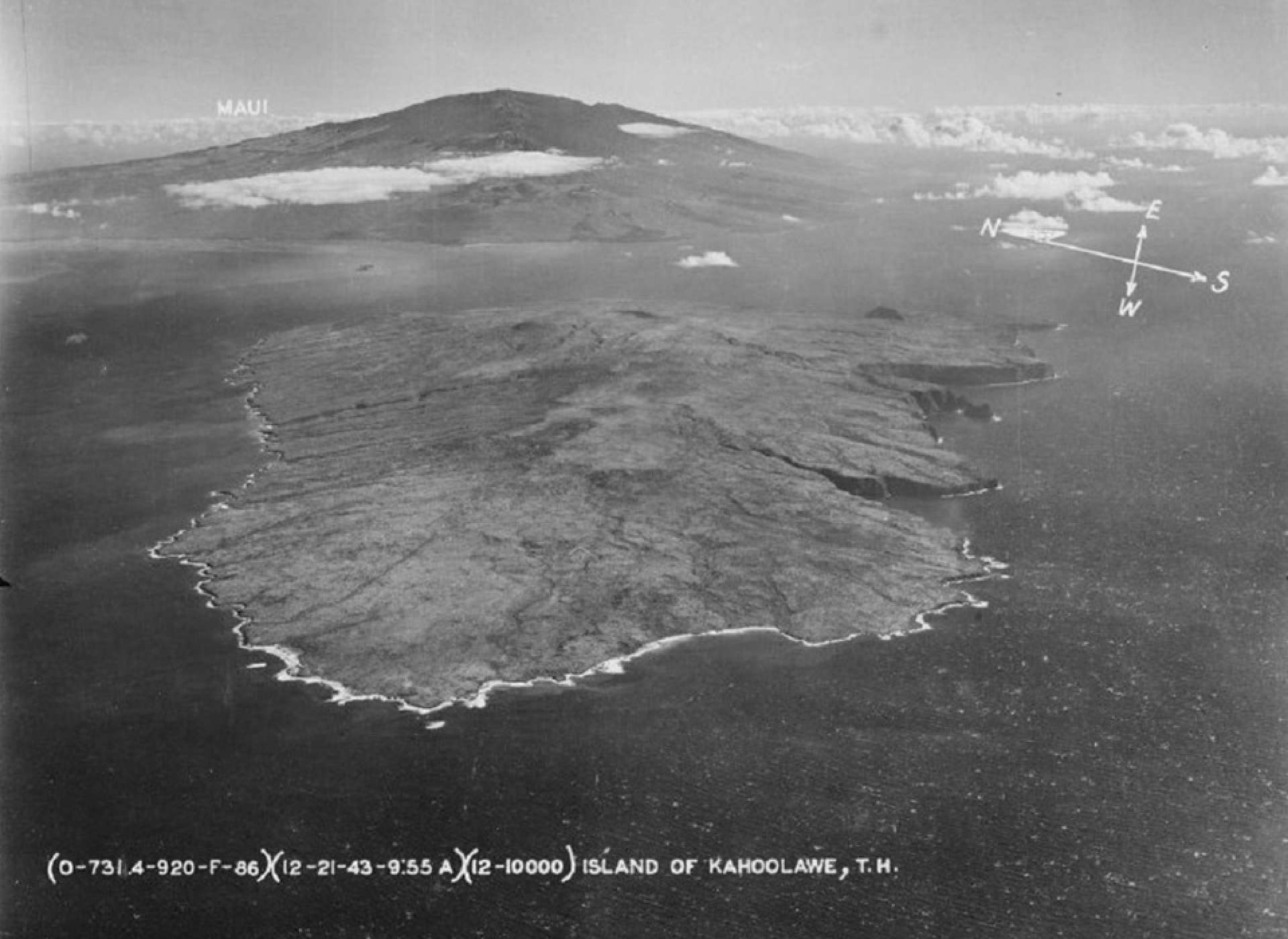

Sitting peacefully in the Pacific Ocean between Maui and Lanaʻi lies Kaho'olawe, a small, windswept island that holds profound cultural and spiritual significance for Native Hawaiians. Known traditionally as Kanaloa, the island is revered as a sacred place of navigation, worship, and connection to ancestral lineage. However, during and after World War II, Kaho'olawe was subjected to decades of relentless bombing and military testing by the United States Navy—leaving behind physical devastation, cultural loss, and environmental trauma that reverberates to this day.

Wartime Beginnings: Kaho'olawe's Strategic Use in WWII

Kaho'olawe's tragic transformation began in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. As fears of Japanese invasion heightened, the U.S. military sought secure and remote locations to conduct training exercises and weapons testing. Kaho'olawe, sparsely populated and largely uninhabited due to its arid environment, was deemed ideal.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order placing Kahoʻolawe under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy. Soon after, the island became a training ground for ship-to-shore bombardment, aerial strafing, amphibious landings, and live-fire target practice. It was systematically pounded by explosives, including high-powered bombs, napalm, and eventually, during the Cold War era, simulated nuclear weapons.

While the island was always considered sacred to Native Hawaiians, its importance was largely ignored by military authorities during this period. Ancient heiau (temples), archaeological sites, and burial grounds were destroyed or damaged beyond recognition. The impact on the island’s fragile ecosystem was similarly catastrophic—vegetation was stripped, topsoil eroded, and entire areas became craters of scorched earth.

Post-War Bombing and the Rise of Resistance

Though World War II ended in 1945, Kaho'olawe's suffering continued. The island was never returned to the people of Hawaiʻi. Instead, it became a permanent part of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet training operations, continuing to be bombed for decades under the rationale of military preparedness.

By the 1970s, amidst a broader Hawaiian Renaissance—a cultural movement focused on the revival of Native Hawaiian identity, language, and sovereignty—activists began to challenge the military’s occupation of the island. A grassroots group called Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) was formed in 1976, led by passionate cultural leaders such as George Helm and Kimo Mitchell. They called for an end to the bombing, the return of the island, and the restoration of its land and sacredness.

PKO’s movement drew national attention. Members of the group staged a series of high-risk occupations by secretly landing on the island to draw attention to its plight. Tragedy struck in 1977 when George Helm and Kimo Mitchell disappeared at sea during an attempt to reach Kaho'olawe—sacrifices that would galvanize support and intensify the movement.

Here is a YouTube video link that showcases some of the bomb test footage from those years:

A Hard-Fought Victory and Partial Restoration

After years of protest, lawsuits, and growing public scrutiny, the U.S. Navy finally ceased live-fire training exercises in 1990, under orders from President George H. W. Bush. Four years later, in 1994, the island was officially transferred back to the State of Hawaiʻi, though it remained under a federal mandate for cleanup.

Congress authorized $400 million for the cleanup effort, known as the Kahoʻolawe Island Conveyance Commission (KICC) project. However, the task was enormous. The U.S. Navy had turned Kahoʻolawe into one of the most extensively bombed islands in the Pacific, and a large portion of the island was still littered with unexploded ordnance (UXO)—including deep-buried munitions that posed long-term hazards.

The goal was to clear at least 100% of the surface and 25% of the subsurface, but due to the dangers and complexities involved, only about 75% of the surface and less than 10% of the subsurface were deemed safe by the time cleanup efforts officially ended in 2003. Much of the island remains off-limits for public access due to these lingering dangers.

Lasting Effects on the ʻĀina (Land) and the People

The legacy of the bombings on Kahoʻolawe is multifaceted—environmental, cultural, and spiritual. The island’s landscape remains scarred by craters, eroded gullies, and large swaths of lifeless land. Its already arid climate, compounded by decades of deforestation and explosive impacts, has made ecological recovery a daunting task.

Culturally, the loss was immeasurable. Ancient stone structures, petroglyphs, and sacred sites were damaged or destroyed. For many Hawaiians, this represented not just a loss of physical artifacts, but a severing of spiritual ties to the land and ancestors.

However, the movement to reclaim and restore Kahoʻolawe has sparked a cultural rebirth. Since the return of the island, restoration efforts have included planting native species, controlling erosion, and reviving traditional practices. Kahoʻolawe is now managed by the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC), which oversees access and stewardship of the island for cultural, educational, and environmental purposes.

Only Native Hawaiians or those involved in official restoration efforts are permitted to visit, and overnight stays are highly regulated. These visits often include ceremonies, chants (oli), and work to heal the land—both symbolically and physically.

A Symbol of Resistance and Resilience

Today, Kahoʻolawe stands as both a symbol of the destructive impacts of militarization and a testament to the resilience of Native Hawaiian culture. It is a living example of how cultural identity, once suppressed and overlooked, can rise again through collective effort, remembrance, and aloha ʻāina—a deep love for the land.

The island’s story continues to inspire movements across Hawaiʻi and beyond, calling attention to the long-term effects of colonization, environmental degradation, and the need for Indigenous stewardship. While Kaho'olawe may never be fully restored to its former self, its journey from devastation to renewal is a powerful reminder that healing is possible—through time, effort, and a commitment to honoring the past.

To Learn More:

These organizations continue the vital work of healing Kaho'olawe and keeping its history alive for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is Kahoʻolawe, and why is it important to Native Hawaiians?

Kahoʻolawe is a small island located between Maui and Lānaʻi, traditionally known as Kanaloa, named after the Hawaiian god of the ocean and navigation. For Native Hawaiians, the island is a sacred cultural and spiritual site, used historically for navigation training, ceremonies, and ancestral connection. Its significance lies not only in its history but also in its role as a symbol of cultural identity, resilience, and aloha ʻāina (love of the land).

2. Why did the U.S. military bomb Kahoʻolawe during World War II and afterward?

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. Navy seized Kahoʻolawe for military training, citing its remote location and sparse population. For decades, the island was used for live-fire bombing, naval shelling, amphibious landings, napalm tests, and Cold War–era simulated nuclear detonations. The military continued using the island long after WWII, claiming ongoing training needs—even though it was a culturally sacred and ecologically fragile place.

3. How did the bombing affect Kahoʻolawe’s land and cultural sites?

The bombing caused severe environmental and cultural destruction. Explosions stripped vegetation, eroded topsoil, and created deep craters. Sacred heiau (temples), petroglyphs, and burial sites were damaged or destroyed. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) remains buried beneath the ground, making large parts of the island unsafe and inaccessible. This devastation disrupted the island’s ecosystem and severed generations of cultural ties.

4. Who started the movement to stop the bombing of Kahoʻolawe?

In the 1970s, during the Hawaiian cultural renaissance, a group called Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) emerged to stop the military occupation. Led by cultural activists including George Helm and Kimo Mitchell, PKO launched a grassroots resistance movement that included protests, legal action, and dangerous landings on the island. Their courage brought national awareness to the cause and became a turning point in restoring Hawaiian cultural pride.

5. When did the military stop bombing Kahoʻolawe?

Live-fire bombing officially ended in 1990 under President George H. W. Bush. In 1994, the island was transferred back to the State of Hawaiʻi, but cleanup efforts continued for years due to the extensive unexploded ordnance left behind. Though military activity has ceased, the scars and hazards remain.

6. Was Kahoʻolawe fully cleaned up after the military left?

No. Despite a $400 million cleanup effort, only about 75% of the island’s surface and less than 10% of its subsurface were cleared of unexploded ordnance. Deeply buried munitions make some areas permanently off-limits. Full restoration is impossible, but ongoing efforts work toward safety, ecological recovery, and cultural renewal.

7. Can you visit Kahoʻolawe today?

Kahoʻolawe is not open to the general public. Access is restricted due to dangerous unexploded ordnance and its designation as a cultural reserve. Only Native Hawaiians or individuals participating in official restoration, cultural, or educational missions through the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) are allowed to visit. Overnight stays require permits and follow strict protocols.

8. What is the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC)?

KIRC is the state agency responsible for protecting, restoring, and managing Kahoʻolawe. Their work includes erosion control, native plant restoration, cultural practices, and environmental monitoring. KIRC aims to fulfill the vision of Kahoʻolawe as a center for cultural education, traditional navigation, and ecological healing.

9. What role does Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) play today?

PKO remains deeply involved in the island’s restoration and cultural revival. They continue to lead ceremonies, cultural training, advocacy, environmental projects, and educational programs. PKO’s work keeps the history, sacrifices, and legacy of Kahoʻolawe alive for future generations.

10. How has the bombing affected Kahoʻolawe’s environment long-term?

Decades of explosives caused extreme ecological damage. The island suffers from:

- Severe soil erosion

- Loss of vegetation

- Cratered landscapes

- Altered watersheds

- Habitat destruction

Despite these challenges, native plants are slowly returning, and large-scale efforts continue to heal the land. Kahoʻolawe is a powerful example of environmental trauma—and resilience.

11. Why is Kahoʻolawe considered a symbol of Hawaiian resistance?

Kahoʻolawe represents the painful impacts of militarization and colonization, but also the strength of Hawaiians who fought to reclaim it. The island embodies the values of aloha ʻāina, cultural revival, environmental guardianship, and unity. Its story continues to inspire Indigenous movements across Hawaiʻi and the Pacific.

12. How can I learn more or support Kahoʻolawe’s restoration?

You can learn more or support restoration efforts through these organizations:

- Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC)

https://kirc.hawaii.gov - Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO)

https://restorekahoalawe.org

Volunteering, donating, or sharing Kahoʻolawe’s story helps ensure the island’s healing continues.

If you would like to read and learn more about interesting things in Hawaii! Check out our blog page here on our website!

or